Key takeaways

Australia’s Property Market has pivoted: Demand is back and Australia’s property market is expected to see continued price growth over the next 12 months, with major capital cities Sydney and Melbourne driving national trends.

Sydney and Melbourne are forecast to lead, as they typically respond more quickly to interest rate changes. Meanwhile, Adelaide and Perth – standout performers over recent years – are expected to experience slower positive growth as affordability constraints intensify.

Unlike the turbocharged growth of the post-COVID boom or the sharp rebounds of past rate-cutting cycles, this future upswing will be defined by subtle shifts in momentum, affordability limits, and policy intervention.

Population growth, tight rental markets, and chronic housing undersupply are key drivers of ongoing demand.

Interest rates have fallen for a third time and many economists expect 2 or 3 further interest rate cuts over the next 6 months which will only improve borrowing capacity and buyer sentiment.

At the same time investor activity is rebounding.

However, not all markets are equal — the gap between top-performing and underperforming suburbs is widening, making strategic property selection more critical than ever.

Long-term fundamentals remain strong — with the right plan, now could be an ideal window of opportunity to invest.

This article is updated monthly, so you always get the most current property data, forecasts, and expert insights.

Scroll down to explore detailed capital city forecasts, interest rate expectations, and expert commentary you won’t find in the mainstream media.

Australia’s property markets are on the move again.

After a period of fragmented property price growth and cautious sentiment, recent developments have brought momentum back into the picture.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has delivered three interest rate cuts this year — most recently lowering the official cash rate to around 3.6% — easing borrowing costs and sparking renewed appetite among buyers.

Home values are climbing steadily, auctions are heating up, and investor activity is surging.

Yet balance remains: affordability remains stretched, supply shortages persist, and not all buyers benefit equally.

However, I see this as the beginning of a new property supercycle. Not a boom, but a period of prolonged property price growth.

But as always, the markets will remain fragmented.

This latest upswing doesn’t negate the fundamentals we laid out previously — Australia’s property market remains underpinned by resilient households, tight supply, and divergent cycles across cities.

What has changed is the tone of the cycle. Where we once saw caution and fragmented performance, we’re now witnessing across-the-board value growth and renewed buyer confidence.

That doesn’t mean the story’s shifted completely — elements like lending buffers, affordability constraints, and ongoing supply shortfalls continue to shape how different markets perform.

In the sections that follow, I am going to revisit revisit my forecasts with fresh eyes — layering in the impact of rate cuts, auction activity, and shifting investor sentiment to help you navigate what really matters for the next 12–24 months.

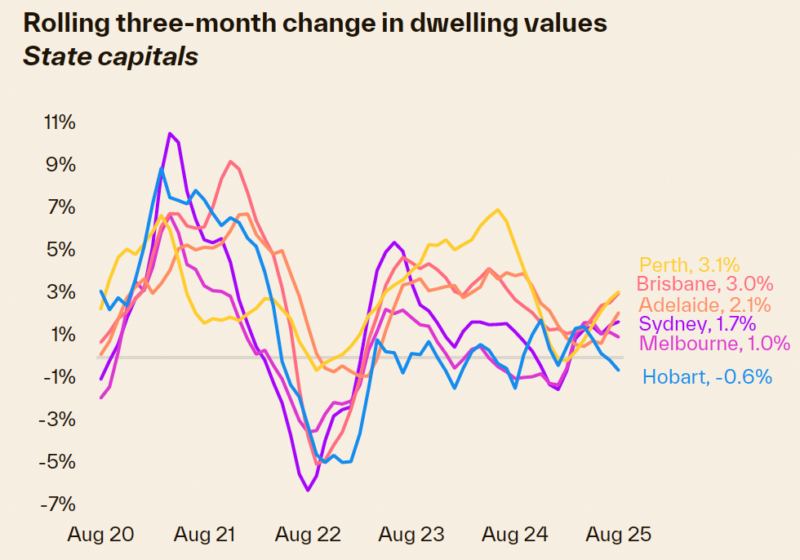

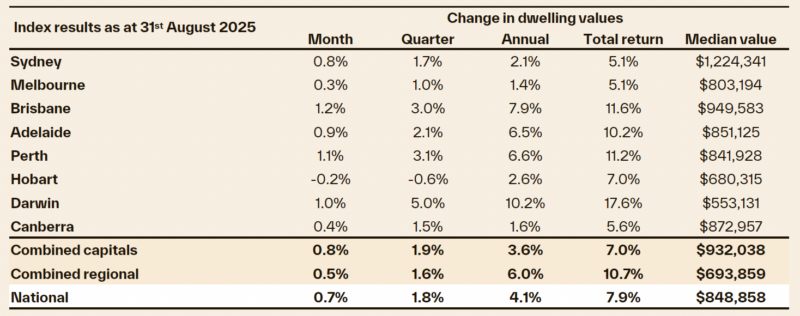

Nationally, Cotality’s Home Value Index rose 0.7% in August — the strongest monthly gain since May 2024 — pushing annual growth to 4.1%.

The mid-sized capitals are once again leading the growth trend, with Brisbane (+1.2%) and Perth (+1.1%) recording the highest monthly gains. Adelaide wasn’t far behind with a 0.9% lift in values.

The latest PropTrack Home Price Index similarly reported that national home prices are up 5.3% over the past year, adding around $47,900 to the value of the median home, and have surged 50.4% in the past five years.

In early April US President Donald Trump announced range of tariffs which posed a significant downside risk to global trade and economic growth but then swiftly reversed them.

Of course global trade tensions pose a significant risk to the world's economic outlook and Australia is not immune, but like all things with Donald Trump, the situation remains fluid and the final outcome remains uncertain.

One of the most significant impacts of Trump's tariffs has been on interest rate forecasts.

The uncertainty and potential slowdown in economic activity has led to increased speculation that central banks, including the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), might lower interest rates even more than previously expected to bolster the economy.

NAB executive chief economist Sally Auld now expects easing interest rates to support property growth and the economy to have a “soft landing” with inflation settling around the middle of the RBA’s target band by the second half of this year and unemployment staying below 4.5pc.

“That said, there are building headwinds in the global economy and shifts in US trade policy are likely to be net disinflationary for Australia.

Consequently, the RBA will need to normalise rates quickly to ensure policy is appropriately calibrated. We now see the RBA cutting to 3.1pc by August and then taking the cash rate to 2.6pc by early-2026.”

The cash rate target was last at 2.6pc in October 2022 – which was at the tail end of pandemic lockdowns.

Of course lower interest rates make borrowing more affordable and in general stimulate our property markets.

There is still a window of opportunity for property buyers to get into the market before further falls in interest rates cause a new flurry of activity later in the year.

The share market’s drama after Trump’s tariff announcements (and re-announcements) reminded me why I invest in property.

There’s something strangely comforting about the opacity of property prices during market turmoil. You can’t obsessively check your property value twenty times a day (though I know a few who’d try if they could).

This information gap might seem frustrating at times, but it’s actually a psychological superpower. It prevents panic selling. It forces long-term thinking.

And it stops you making decisions in the heat of emotion that you’ll regret when cooler heads prevail.

Note: Don't make 30 year investment decisions based on the last 30 minutes of news.

Sure there are turbulent times ahead, but our housing markets are well positioned to weather them.

RBA data shows that less than 1% of households are in negative equity, a vast improvement from around 1.5% in early 2019 before Covid.

The majority of mortgage holders have loan-to-valuation ratios well below 80%, with many clustered in the 40–60% range.

In fact 50% of home owners have paid off their mortgage.

This means that, even if Australia has an economic downturn and unemployment rises, most borrowers have the flexibility to manage their situation — including the ability to sell without taking a loss.

Sure recent borrowers with high debt levels and thinner buffers are more at risk, but forced sales are likely to remain low, even if unemployment rises.

This overall financial resilience of Australian households is a critical cushion for both the property market and broader economic stability.

Back to what's happening in the Australian Property Markets

Of course, each state is at its own stage of the property cycle and within each capital city there are multiple markets.

While regional property markets became popular with homebuyers wishing to escape Covid a couple of years ago, and more recently regional markets were attractive to investors because of their comparatively lower prices, over the long term capital city property markets have outpaced regional areas and this trend is likely to continue.

Overall, persistently low supply relative to demand are supporting housing values despite high interest rates, ongoing cost of living pressures, worsening affordability pressures and a deeply pessimistic level of consumer confidence.

The gap between capital city house and unit values has widened substantially.

Capital city house values rose almost 3 times as much as unit values since the onset of Covid... but the gap is narrowing across most cities.

And after underperforming throughout the pandemic period, unit prices recorded stronger growth for much of 2025 as affordability constraints will mean more Australians trade backyards for balconies and courtyards this year.

However the chart below shows the significant gap in property price growth between these two types of dwellings.

The good news is that this creates a window of opportunity, as one can now buy established family friendly apartments considerably below replacement cost.

Here's the forecast for property prices in 2025-26

Domain’s latest Price Forecast Report for FY25-26 reveals that Australia’s property market is expected to see continued price growth over the next 12 months, with major capital cities Sydney and Melbourne driving national trends.

Unlike the turbocharged growth of the post-COVID boom or the sharp rebounds of past rate-cutting cycles, this future upswing will be defined by subtle shifts in momentum, affordability limits, and policy intervention.

The range of capital city price growth is expected to narrow.

Sydney and Melbourne are forecast to lead, as they typically respond more quickly to interest rate changes. Meanwhile, Adelaide and Perth – standout performers over recent years – are expected to experience slower positive growth as affordability constraints intensify.

Brisbane unit prices are expected to moderate from the previously unsustainable double-digit growth, while house prices continue to grow at a pace similar to that of last year.

Domain's House price forecasts

| HOUSES | STRATIFIED MEDIAN PRICE | ||||||

| ANNUAL CHANGE | LEVEL | RECORD | BELOW PEAK | |||

| Capital City | FY25 | FY26 | FY25 | FY26 | FY26 | FY26 |

| Sydney | 4% | 7% | $1,717,107 | $1,829,576 | YES | |

| Melbourne | 0% | 6% | $1,046,246 | $1,112,623 | YES | |

| Brisbane | 5% | 5% | $1,037,357 | $1,093,414 | YES | |

| Adelaide | 12% | 4% | $1,013,204 | $1,049,117 | YES | |

| Canberra | -2% | 4% | $934,225 | $981,808 | NO | -7% |

| Perth | 7% | 5% | $934,225 | $981,808 | YES | |

| Combined capitals | 4% | 6% | $1,194,942 | $1,264,614 | YES | |

Domain's Unit price forecasts

| UNITS | STRATIFIED MEDIAN PRICE | ||||||

| ANNUAL CHANGE | LEVEL | RECORD | BELOW PEAK | |||

| Capital City | FY25 | FY26 | FY25 | FY26 | FY26 | FY26 |

| Sydney | 3% | 6% | $835,819 | $888,822 | YES | |

| Melbourne | -3% | 5% | $555,522 | $584,400 | NO | -3% |

| Brisbane | 12% | 5% | $670,798 | $701,490 | YES | |

| Adelaide | 10% | 3% | $568,000 | $586,366 | YES | |

| Canberra | -13% | 3% | $531,784 | $546,265 | NO | -15% |

| Perth | 12% | 6% | $519,551 | $552,487 | YES | |

| Combined capitals | 3% | 5% | $680,568 | $717,266 | YES | |

History suggests that once rates start falling, property prices don’t wait around.

Bank of Queensland chief economist Peter Munckton has crunched four decades of data which was reported in the Financial Review and said a 10 to 15 per cent price rise over the next two years is a reasonable bet – no matter how many cuts the RBA ends up delivering.

Munckton explained...

“There were smaller price rises in both the early 1980s and 1990s.

But on both those occasions, the unemployment rate was above 10 per cent.

Currently, the unemployment rate is within touching distance of 50-year lows,”

On the flip side, Munckton says the extraordinary 20 per cent-plus gains seen in the ’80s, ’00s and during the pandemic also seem off the cards over the next couple of years

Tip: The expansion of the first homebuyer support will add further fuel to our housing markets

From January 1 2026, virtually all first home buyers will be able to enter the market with just a 5 per cent deposit, via a taxpayer-backed guarantee.

This part of his election promise, prime minister Anthony Albanese promised to turbocharge the program by scrapping the $125,000 income cap, making it available to an unlimited number of applicants instead of just 35,000 per year, and dramatically raising property price thresholds.

A separate promise to build 100,000 new homes was also made – but that extra supply could take years to arrive, if it arrives at all.

Apartment rents set to surge over the next few years.

Median apartment rents are likely to grow by 24% between 2025 and 2030, across Australian capital cities, according to the latest report by International Property Consultancy, CBRE.

By 2030, 92% of 2-bed apartments are forecast to have rents exceeding $700/week (33% exceeding $1000/week)

CBRE expect that capital city vacancy rates will fall further to 1.1% by 2030 from 1.8% in 2025.

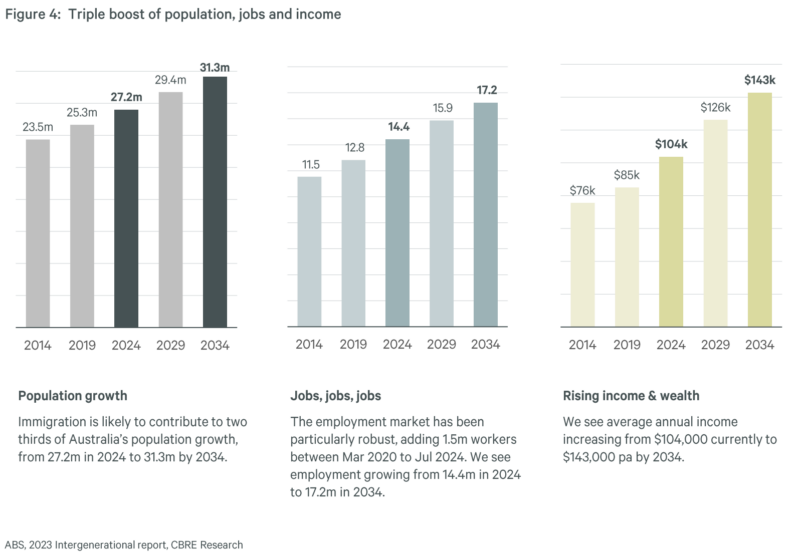

Over the next 10 years, demand for housing is expected to benefit from a triple boost: rising population (+4.1 million), rising jobs (+2.8 million), and rising income (+$39k).

CBRE estimates around $960 billion of additional income in the system to support mortgage, rent, and other living expenses.

You can always beat the averages.

While it’s likely that property price growth will take off in the second half of 2025, the good news is that you can always beat it by investing in the right property in the right location.

Now by that, I don’t mean look for the next hotspot.

I mean buying quality properties in locations that will outperform in the long term such as gentrifying suburbs.

You see...property offers countless opportunities to improve your results through your own time, skills and knowledge – so you don’t need to settle for average.

And there’s more to it than just location. You can add value through refurbishment, or redevelopment.

What does the third RBA interest rate cut mean for our housing markets?

Knowing the Board’s strong preference for quarterly inflation data, it will likely wait until the 3-4 November meeting before cutting the cash rate again, provided the September quarterly CPI results, due out on 29 October, remain on track.

| Current big four bank cash rate forecasts | |||

| Bank | Next cut | Total no. cuts to come | Cash rate at end of cuts |

| CBA | 4 November | 1 | 3.35% |

| Westpac | 4 November | 3 | 2.85% |

| NAB | 4 November | 2 | 3.10% |

| ANZ | 4 November | 1 | 3.35% |

A single 0.25 percentage point cash rate cut, if fully passed on by lenders, could reduce monthly repayments on a $600,000, 25-year mortgage by $90.

If Westpac’s forecast plays out, with four rate cuts through to mid-next year, homeowners could see a total drop of $349 a month.

| Impact of four potential rate cuts | ||

| Monthly repayments | Total change from today | |

| Current | $3,793 | - |

| 1 cut | $3,703 | -$90 |

| 2 cuts | $3,615 | -$178 |

| 3 cuts | $3,528 | -$265 |

| 4 cuts | $3,444 | -$349 |

| Source: www.canstar.com.au. Notes: based on owner-occupier paying principal and interest with 25 years remaining in July 2025 on the estimated RBA average variable rate of 5.80%. Assumes cash rates cut are in August, November, February and May and passed on in full the month after. | ||

However, the benefits from the rate cut will not be distributed equally.

High-income earners with significant equity in their properties are likely to feel more confident in re-entering the property market than Aussie battlers who have been hurt by the cost of living crisis and who are unlikely to notice a significant change in their budget with this 0.25% cut in their mortgage rates.

Historically, when interest rates fall, buyers who have been sitting on the sidelines are enticed back into the market and property values start to increase as buyer confidence increases before seller confidence, making these new home buyers compete for the limited stock of properties available.

Traditionally, the premium suburbs in Sydney and Melbourne have led the market in price rebounds after interest rate cuts.

This time around it is likely that the 0.25% interest rate cut will stabilise house prices in Melbourne and Sydney, which have been falling over the last few months, rather than igniting the next phase of the property cycle.

The increased confidence brought about by the drop in interest rates may be all the Melbourne housing market needed to pick up from its four-year slump.

While the affordable end of the Melbourne market out performed over the last few years, as more affluent homeowners “sat on their hands”, it is like the increased confidence that the interest rate drop will bring will now encourage these homeowners to get on with their life plans.

And with Melbourne being relatively cheap compared to other cities, more and more property investors are taking advantage of the window of opportunity to get into Australia’s second biggest housing markets prices that won’t be available in a year or two's time.

How can values continue rising amid high interest rates and the cost of living crisis?

Clearly affordability has decreased, but the housing markets are being underpinned by a number of factors:

- Wealthy buyers entering the market with higher deposits.

- Downsizers who had a lot of equity in their homes are buying debt free - in fact a third of properties last year were transacted with no mortgage at all.

- The bank of mum and dad and inheritances are helping many buyers with a deposit.

- The recent first home buyer incentives offered by both major political parties will increase demand at a time of lack of supply further pushing up prices, especially at the lower end of the market.

- Some buyers are buying in cheaper markets while others are buying units rather than houses.

- Rentvestors will keep buying investment properties while renting in their preferred living locations

The latest housing market stats

Corelogic report similar figures to Proptrack suggesting that in annual terms, Australian home values were up 4.9% in 2024, adding approximately $38,000 to the median value of a home.

Here are the latest stats provided by CoreLogic for property price changes around Australia:

Source: Cotality HVI 1st September 2025.

We also keep track of “Asking Prices” as these are a good leading indicator for the property market because they reflect the sentiment of sellers and their expectations for the future value of their homes.

Sydney Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 2,082,822 | 10.178 | 2.3% | 9.4% |

| All Units | 875,607 | 4.893 | 1.2% | 6.3% |

| Combined | 1,590,745 | 8.024 | 2.1% | 8.4% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Melbourne Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 1,302,817 | 2.423 | 0.6% | 5.4% |

| All Units | 641,186 | 0.814 | 0.9% | 5.4% |

| Combined | 1,093,577 | 1.914 | 0.6% | 5.3% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Brisbane Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 1,284,314 | 2.104 | 1.1% | 8.9% |

| All Units | 770,220 | 7.980 | 3.3% | 18.6% |

| Combined | 1,154,901 | 3.583 | 1.5% | 10.3% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Perth Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 1,169,823 | -4.325 | 1.3% | 8.8% |

| All Units | 673,885 | 9.481 | 2.1% | 19.9% |

| Combined | 1,039,083 | -0.705 | 1.4% | 10.4% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Adelaide Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 1,059,406 | 4.584 | 0.6% | 10.4% |

| All Units | 568,136 | 1.164 | 0.7% | 20.6% |

| Combined | 970,984 | 3.968 | 0.6% | 11.3% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Canberra Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 1,246,438 | 22.174 | 1.2% | 7.9% |

| All Units | 581,575 | -2.700 | -1.2% | -2.0% |

| Combined | 997,253 | 12.851 | 0.6% | 5.1% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Darwin Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 779,010 | -8.010 | -1.8% | 16.6% |

| All Units | 440,548 | -0.548 | 0.1% | 14.9% |

| Combined | 645,948 | -5.076 | -1.3% | 16.1% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Hobart Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 849,230 | 0.770 | 1.0% | 9.5% |

| All Units | 488,706 | -1.606 | -1.7% | -0.4% |

| Combined | 794,244 | 0.407 | 0.7% | 8.4% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

National Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 1,023,895 | -2.436 | 1.5% | 9.4% |

| All Units | 605,581 | 3.219 | 1.8% | 8.0% |

| Combined | 933,259 | -1.211 | 1.5% | 9.1% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

Capital Cities Property Asking Prices

| Property type | Price ($) | Weekly Change | Monthly Change % | Annual % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Houses | 1,507,054 | 3.660 | 1.7% | 8.5% |

| All Units | 758,845 | 4.791 | 2.3% | 8.4% |

| Combined | 1,283,801 | 3.997 | 1.8% | 8.3% |

Source: SQM Research, September 2025

The fundamentals of what drives Australian property prices

Property prices are driven by a combination of factors, and as we move through property cycles, they all come together to influence whether property values rise or fall.

If you take a telescopic view, rather than a microscopic view, and look at what's ahead for housing markets over the next decade or two, the two big factors driving our housing markets will be demographics (how many of us there are, have we want to live and where we want to live) and the wealth of the nation.

But first, let’s dig a bit deeper into the key underlying factors that will be influencing our property markets in the medium term.

1. Interest rates/affordability

While many people believe interest rates are a key driver of property values, and that's why there were so many pessimistic property forecasts as interest rates rose through 2022-23, our housing markets showed considerable resilience and kept rising in value despite the 13 interest rate rises the RBA threw at us.

Of course, falling interest rates and the subsequent increased affordability are strong drivers of property price growth, but the reverse isn't true.

House prices are driven by many other factors, not just interest rates, but rates are on the way down.

2. Supply and demand

Housing supply has a significant influence over house prices in the short term: an undersupply puts pressure on prices to rise while an oversupply does the opposite.

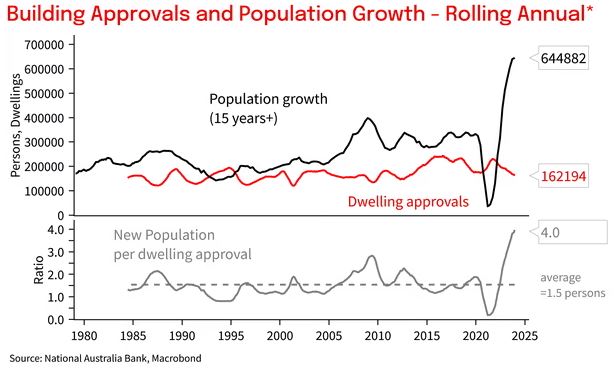

Despite very strong population growth, we’re just not building enough new dwellings, and this has put pressure on housing supply reflected in low rental vacancy rates and higher house prices.

At the same time, the strong absorption of new listings for sale has kept total listings in the market suppressed, intensifying competition between buyers.

These factors have created a sharp shortage of housing, outweighing the negative impact of rates on prices.

And there is no end in sight as building approvals (which are a good indication of future supply) are running at very low levels.

And just because a new apartment complex has been approved, it doesn't mean it will get built.

At the moment very few new complexes are coming out of the ground because it's not financially viable to build them at today's market prices.

Of course, this means future new developments will have to sell at prices considerably higher than today’s market value and this will, in turn, pull up the value of established apartments.

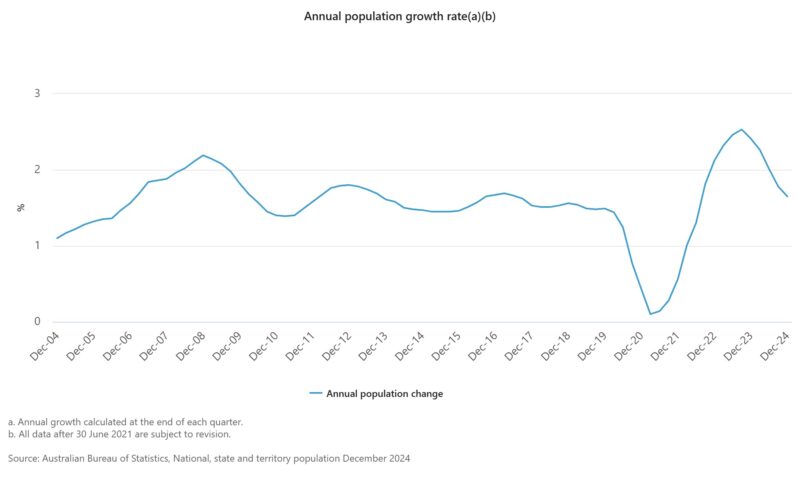

The surge in population growth to a record 660,000 last year, driven by record immigration levels meant that around an extra 250,000 new homes needed to be built last year alone.

But instead, completions have been running around 170,000 as the home building industry struggles to keep up with rising costs and material and labour shortages and as approvals to build new homes fell.

In fact it has been "conservatively" estimated that we have an accumulated housing shortage of around 200,000 dwelling currently, and it is unlikely our housing shortage will be resolved in the next decade, maybe we will have continue continuing pressure for rising house prices and rents.

3. Consumer confidence

Consumer confidence is a critical factor affecting the direction of property prices.

We don't make big financial decisions like moving home or buying an investment property unless we feel confident about our economic future and our financial stability.

Consumer confidence has been at historic lows because of all the economic and socio-political issues that have confronted us, but has picked up recently.

I believe that during 2025 consumer confidence will continue to rise as it becomes obvious that inflation is under control and interest rates will eventually fall.

At the same time, the “wealth effect” of an improving economy and rising property values will lead to further consumer confidence and bring home buyers and sellers back into the market.

4. Economic climate

Another key factor that affects the value of the property market is the overall health of the economy.

This is generally measured by economic indicators such as the gross domestic product (GDP), employment data, manufacturing activity, the prices of goods, etc.

While the RBA has been trying to slow our economy down to bring inflation under control, currently, everybody who wants a job can get a job and this will underpin our housing markets even if the economy falters a little moving forward.

5. Population growth

In the year ending 30 June 2024, overseas migration contributed a net gain of 446,000 people to Australia's population.

This was a decrease from the record 536,000 people the previous year once the floodgates were opened as we worked our way out of the Covid Pandemic.

While population growth has always been a key driver supporting our property markets, the influx over the last few yearshas pushed our supply/demand balance off-kilter and is key to the increase in housing prices and the shortage of rental properties.

6. Availability of credit

When the credit (the ability to borrow from the banks) is readily accessible, with lower interest rates and less stringent lending criteria, it tends to stimulate the housing market since more people find themselves able to borrow money to buy homes, leading to increased demand for housing.

On the flip side, when credit is tightened through higher interest rates or stricter lending criteria (as happened when APRA made the banks tighten the purse strings in 2016-7), the effect can be a cooling of the housing market.

Such measures are usually a deliberate policy response to an overheated market, aiming to reduce the risk of a “property bubble” and subsequent crash.

7. Investor Sentiment

This sentiment, essentially the collective attitude and outlook of investors towards property markets, can significantly influence both the demand for and the value of real estate.

Investors generally account for around one-third of all property transactions so positive investor sentiment can drive up property prices, especially in sought-after areas.

Conversely, negative investor sentiment, as occurred during the market downturn of 2022, can lead to a decrease in property values.

If investors believe that property prices will stagnate or fall, they may be less inclined to invest, or they might choose to sell off their properties, increasing supply in the market.

8. Government incentives

Government incentives can have both direct and indirect impacts on the real estate sector.

One of the most direct ways government incentives affect property values is through policies aimed at stimulating demand.

For instance, initiatives like the First Home Owner Grant (FHOG) or stamp duty concessions for first-time buyers directly increase buying capacity, leading to greater demand for property.

Another aspect is the development incentives provided by the government to promote specific types of property development, such as high-density housing or urban renewal projects.

These incentives can increase property values in targeted areas by improving infrastructure, accessibility, and community facilities, making them more desirable places to live.

Tax policies and regulations also play a crucial role.

Negative gearing can increase demand for investment properties, pushing up prices.

And every time there is talk about removing negative gearing or amending taxes including land tax, investors shy away from our housing markets.

Australian housing market predictions for 2025 and 2026

The last few years have shown us how hard it is to forecast property trends, and as always there will be headwinds and tailwinds buffeting our property markets.

Currently Australia’s housing is so undersupplied that I've rarely encountered a supply-demand inflection point like this that requires such attention.

And it’s only going to get worse.

Drivers of property price growth in 2025 will include:

- Continued strong population growth at a time when we are not producing enough supply of new dwellings. This extreme shortfall will exert upward pressure on house prices and rents throughout 2025.

- Interest rates will continue to fall through 2025 and at some stage it is likely APRA will relax its mortgage serviceability buffer. This is currently at 3% and the combination of these factors will increase borrowing capacity.

- FOMO (fear of missing out) will creep in as buyers realise that real estate values are rising and as the media will keep mentioning new record prices being achieved.

Headwinds:

- Stretched affordability will remain an issue in 2025, however, buyers will want to get on with their lives and therefore choose townhouses or apartments over homes or move to more affordable suburbs.

- Geopolitical problems and talk about a recession may lead to some financial uncertainty and worries about job security which could stop some buyers from making important decisions like buying a home or an investment property.

- Poor consumer sentiment was a feature of much of the last few years, holding back property buying decisions, and until there is more certainty about our economy and confidence that interest rates have peaked and inflation is under control, it's likely that consumer confidence will remain low until interest rates start falling.

The strongest performers are likely to be Brisbane and Perth, where population growth is expected to outpace supply more than in other cities.

With the increase in value of houses strongly outpacing the apartment market recently, now with the differential in price between units and houses at the highest level on record, and with houses becoming more unaffordable for many, I can see strong capital growth ahead for family-friendly apartments in great neighbourhoods.

8 economic and property trends to watch out for moving forward

1. The recovery phase of the market will continue throughout 2025

Property price growth will continue throughout 2025, albeit at a much lower rate and our housing markets will be fragmented as affordability will affect many homebuyers.

2. Interest rates will fall

Interest rates will keep falling over the year with probably a rate cute every 3 months (quarterly) and this will likely encourage greater housing investment and more homebuyers.

3. Our property market will be even more fragmented

Of course, there was really never "one" Sydney property market or one Melbourne property market.

There are markets within markets – there are houses, apartments, townhouses and villa units located in the outer suburbs, middle ring suburbs, inner suburbs and the CBD, and they're all behaving differently.

But our markets will be much more fragmented moving forward as some demographics struggle with cost-of-living, rent and mortgage cost increases (at a time of low wage growth) more than others.

It will either stop them from getting into the property markets or severely restrict their borrowing capacity which will negatively impact the lower end of the property markets.

Meanwhile, many first-home buyers who borrowed to their full capacity will have difficulty keeping up with their mortgage payments at the time of rising interest rates or when their fixed-rate loans convert to variable rates.

In other words, there will be little impetus for capital growth at the lower end of the property market.

That's why I would only invest in areas where the locals’ income is growing faster than the national average - such as gentrifying suburbs - as locals will have higher disposable incomes and be able to and are likely to be prepared to pay a premium to live in these locations.

Many of these locations are the inner and middle-ring suburbs of our capital cities which are gentrifying as these wealthier cohorts move in.

At the same time, I see well-located properties in our capital cities outperforming regional property markets.

In fact our capital cities outperformed regional housing markets over the last year or so.

In the past one of regional Australia's allure was its affordability compared to capital cities.

However, the surge in prices over the COVID lockdowns narrowed the price gap and this diminishing affordability undermines one of the key advantages regional markets had over metropolitan counterparts.

The measure of years to save a 20% deposit for the median regional home on a median regional income has risen from 7.4 years in early 2020 to 9.7 years, as opposed to 10.0 years for capital cities.

4. Migration

Net overseas migration to Australia will remain strong in 2025, however, the Federal government will lower the rate of temporary migrants coming to Australia and is planning to reduce international student intake to Australia.

However, the influx of immigrants will keep driving rental growth as migrants tend to rent.

Only 38% of migrants own a home after being in Australia for five years, yet 71% of migrants own their home after 10 years.

5. Rents will keep rising

There is no end in sight for our rental crisis and rent prices will continue skyrocketing into 2024.

In fact, increased rental demand at a time of very low vacancy rates will see rentals continue to rise throughout the next few years.

6. Strategic investors will keep entering the property market

And they’ll squeeze out first-home buyers.

As rents continue to rise and the share of first-home buyers continues dropping, strategic investors with a realistic long-term focus will return to the market.

7. Neighbourhood will be more important than ever

In our post Covid world, people will pay a premium for the ability to work, live and play within a 20-minute drive, bike ride or walk from home.

Many inner suburbs of Australia’s capital cities and parts of their middle suburbs already meet the 20-minute neighbourhood tests, but very few outer suburbs do because there is a lower developmental density, less diversity in its community, and less access to public transport.

And ‘neighbourhood’ is important for property investors too, and here’s why.

In short, it’s all to do with capital growth, and we all know capital growth is critical for investment success, or just to create more stored wealth in the value of your home.

This is key because we know that 80% of a property’s performance is dependent on the location and its neighbourhood – in fact, some locations have even outperformed others by 50-100% over the past decade.

And it’s likely that moving forward, thanks to the current environment, people will place an even greater emphasis on neighbourhood and inner and middle-ring suburbs where more affluent occupants and tenants will be living.

These ‘liveable’ neighbourhoods with close amenities are where capital growth will outperform.

What sets these neighbourhoods apart is the demographics – these locations are generally gentrifying or are lifestyle locations and destination locations that aspirational and affluent people want to live in.

So lifestyle and destination suburbs where there is a wide range of amenities within a 20-minute walk or drive are likely to outperform in the future, fetching premium prices in 2024.

8. Our economy and employment will remain robust

Our economy will keep growing (albeit a little slower) and the unemployment rate will remain low thanks to the many new jobs created as our economy grows.

Local Capital Cities Market Predictions for 2025

As we know, there is not one Australian housing market, but markets within those markets, and again within those.

As interest rates fall over the next year or two, confidence will return, and buyers will return to the property markets.

However, affordability will still be an issue for many potential buyers, and buyers will only be able to pay up to the limit of what they can afford, so I would only invest in locations where wages are increasing faster than average, and residents have multiple streams of income, not just wages.

This means the more affluent inner-ring suburbs and the gentrifying middle-ring suburbs of our capital cities will outperform the cheaper suburbs, where residents will still find it difficult to afford to buy a home.

Melbourne housing values led gains in March with a gain of 0.5%. February's rate cut boosted borrowing capacities, and improving affordability and buyer confidence have driven renewed demand and price growth.

After a period of sustained higher interest rates, buyers who held off purchasing are re-entering the market.

Auction clearance rates have strengthened, reflecting renewed competition.

Despite the bounce in March, prices in Melbourne remained 2.6% below their levels a year ago.

Price momentum has been weaker in Melbourne for much of the past five years, partly due to weaker economic conditions, greater buyer choice and higher property taxes.

Additionally, construction activity in Victoria has aligned more closely with population growth over the past decade.

However, this creates a window of opportunity for strategic property investors as Melbourne property values have significant upside potential.

At Metropole Melbourne, we’re finding that on-the-ground sentiment has changed and strategic investors and homebuyers are accepting that inflation has probably peaked and that interest rates are likely to peak in w months, so they are getting on with property decisions.

While more buyers are active in the market, there is currently a shortage of good quality stock on the market - while house prices have been resilient, Melbourne rental rates are experiencing weaker conditions due to a higher supply of rental properties, and less demand.

Sydney’s housing values lifted 0.3% in March to a record high and were 0.9% above their levels a year ago.

Market sentiment has improved now interest rates have started to move lower.

As a result of the boost to purchasing power, price falls in Sydney have reversed.

The improvement in affordability and buyer confidence has driven renewed demand and price growth.

Buyers who had delayed purchases due to the sustained higher interest rate environment are re-entering the market and stronger auction clearance rates reflect renewed competition among buyers.

The Brisbane’s housing market lifted 0.4% in Marcch to a record high, with prices up 8.6% over the past year.

Brisbane remains one of the strongest-performing capital city markets comparing annual price growth, though there has been a deceleration in the pace of price increases compared to the previous quarter.

Although growth is moderating, this follows a run of exceptional growth that has seen Brisbane become the second-most expensive capital, ahead of Melbourne and Canberra, with prices up 81% over the past five years.

Our on-the-ground experience at Metropole Brisbane shows that there is emerging strong demand from both home buyers and property investors for A-grade homes and investment-grade properties.

Perth’s housing values lifted a small 0.2% in March

Though the pace of growth has slowed compared to the previous quarter, Perth remains the top-performing capital for annual home price growth (+11.9%).

The comparative affordability of the city's homes, strong population growth and limited new housing supply have all contributed to the city's persistently strong growth in recent years.

Driving Perth’s outperformance has been strong population growth as well as high levels of investor demand, however, I would be cautious about buying in many of the cheaper Perth suburbs where investors are buying at the current prices because they’ve run ahead of the broader market.

Once investor demand from the East Coast slows down, these areas are going to weaken first.

The smart money would have been there 2-3 years ago – and is now focused on other states that are early in the growth cycle.

Adelaide’s housing values - prices lifted 0.8% in March, bringing prices to a record high.

Adelaide remained one of the top-performing capitals over the past year, as prices were 11% above March 2024 levels.

The comparative affordability of the city's homes has contributed to persistently strong growth in recent years.

However, the pace of price growth has slowed in line with affordability deteriorating significantly through

Canberra’s property prices lifted 0.2% over the month of March yet were sitting 0.5% below their March 2024 levels.

Hobart’s housing values dropped 0.4% in March, marking the fourth consecutive month of falls.

Hobart prices are now -0.2% lower than the same time last year.

Even so, Hobart remains the weakest capital city market when comparing change from peak, with prices down 7.38%, despite recovering some of their two-and-a-half-year decline in the second half of 2024.

Darwin home prices lifted 1% in March to a fresh price peak, up 2.6% over the past year.

Long-term forecasts for Australian property markets (2025-2030)

Over the next decade, demand for housing is expected to benefit from the triple boost of rising population, rising jobs, and rising income.

Collectively this wealth effect will add around $860 billion of income over the next decade, a significant portion of which is likely could be directed towards housing.

The average Australian tend to spend 13% to 20% of their income and either rent or mortgage servicing.

Of course, no matter how many times you forecast property prices, it will always be difficult to predict exactly where property markets and prices will be in three months' time, let alone 6-7 years into the future.

After all, history shows us that some properties will outperform others by 50-100% in terms of capital growth, so strategic property investors who buy investment-grade properties could expect to see the value of their properties more than double within the next seven to 10 years.

So we always have to take forecasts for Australian property markets with a big pinch of salt.

But what I am confident we’ll see for our future property markets comes off the back of our strong projected population increase.

Currently, there are about 27.6 million Australians and Australia's population is forecast to rise to over 30 million people by 2030.

This means close to 3 million more people will need somewhere to live and this will underpin our property markets.

What we predict for Australia’s property market is that there will be many more high-rise towers of apartments, not just in the CBD but in our middle-ring suburbs.

In fact, we are already starting to see this, particularly in Melbourne and Sydney.

And we also expect there will be lots more medium-density housing – in particular townhouses will be a popular way to live with modern large accommodation on more compact blocks of land.

So what about property prices for 2025-2030?

Some economists predict a 40-50% growth in Australia's house prices between now and 2030.

This isn’t surprising because it’s often said that over the long term, the average annual growth rate for well-located capital city properties is about 7% (and we know that prices have risen 6.8% per annum over the past 30 years), which would mean, in general, well-located properties should double in value every 7-10 years.

That would put Australia’s median dwelling price at around $1.1 million in 2030.

Final Thoughts: So, Where to From Here?

Our property markets are on the move

-

Confidence is recovering.

-

Rate cuts are on the way.

-

Prices are already lifting in key markets.

-

Rental demand remains tight.

-

And we still aren’t building fast enough.

From a strategic investor’s perspective, this is classic countercyclical territory.

When mainstream sentiment is still cautious but forward-looking indicators are improving, that’s your window of opportunity.

At Metropole, we’ve always believed that successful investing is about understanding cycles, acting with clarity when others are uncertain, and buying the right property in the right location—not just chasing what's hot.

This report confirms that the right time to act may be sooner than many realise.

At Metropole, we’ve helped thousands of clients safely navigate all stages of the property cycle. With our proven frameworks and data-driven approach, we can help you grow, protect, and pass on intergenerational wealth.

Tip: Need some clarity? Why not start with a complimentary Wealth Discovery Consultation with one of our Property Strategists? Leave us your details here.

Bookmark this page and check back regularly — we update this forecast often to reflect the latest insights and trends.

The property market never stands still, and neither should you.