Key takeaways

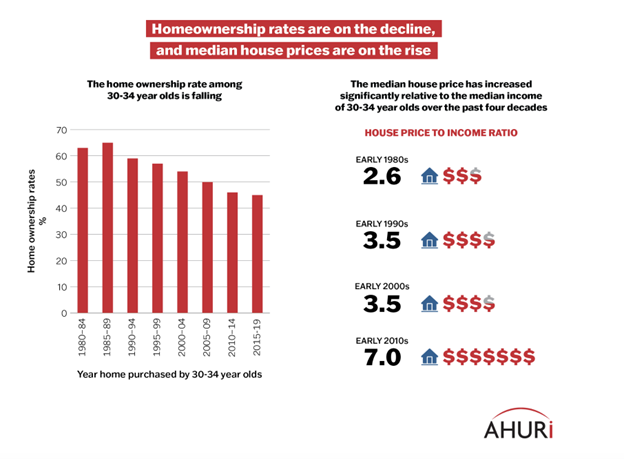

ABS data shows that the trend for home ownership among our younger generation is on a downward trend, and affordability is a key issue.

Skyrocketing property prices, stringent lending criteria, and economic instability have made it much harder for young Australians to save a deposit and secure a home loan.

The government announced plans to encourage the construction of 1.2 million new homes in 5 years and increase new rental properties by 150,000 over the next 10 years, but the number of dwellings completed is way off what is actually needed, resulting in low rental vacancy rates and higher house prices.

Building approvals are very low, which means that future apartment complexes will have to sell at prices considerably higher than today's market value.

Young Australians are redefining success and stability, prioritising experiences, flexibility, and urban living over the traditional path of owning a home. The housing market must adapt to meet these changing needs.

It’s clear that the trend for home ownership among our younger generation is on a downward trend, and while affordability is a key issue, there is more than meets the eye.

ABS data shows that over half (55%) of Millennials, in the age bracket 25-39 years old, are homeowners compared with 62% of Generation X and two-thirds (66%) of Baby Boomers when they were at the same age.

Of course, there is no denying that skyrocketing property prices, stringent lending criteria, and economic instability have made it much harder for young Australians to save a deposit and secure a home loan.

According to Corelogic research, Australia's national median dwelling value delivered a 6.8% annual growth rate over the 30 years to March 2022, with the 1992-2002 period providing the largest capital gains.

The middle decade (2002-2012) saw national dwelling values increase by 59%, while the most recent decade increased by 72%.

Source: CoreLogic

Over the same period, the price of property has outpaced wage growth 3-to-1, further supporting the belief that increasing house prices and falling affordability are closely associated with a delay in housing market entry for Australian households.

At the same time, Australia’s financial environment has become more challenging.

Lenders now require larger deposits and stricter proof of financial stability, making it tougher for young people to secure a mortgage.

Add to this the rising costs of living and stagnant wage growth, and it's clear why many young Australians feel priced out of the property market.

But while many blame unaffordability issues and a high cost of living for the reason these Aussies aren’t taking a step onto the ladder, it doesn’t paint the whole picture.

A closer look at this cohort reveals that changing lifestyle choices and values are equally significant factors delaying homeownership for today's youth.

The lifestyle shift of Australia’s younger generations

Focusing solely on economic factors overlooks a crucial part of the puzzle.

From marriage, relationships, children and increased flexibility, young Aussies are buying homes later than their parents did choosing a different lifestyle, not necessarily only affordability issues.

And because today's young Australians are making different lifestyle choices compared to their parents, it significantly impacts their approach to homeownership.

Here are a number of ways that the lifestyle changes of today’s youth have affected homeownership rates.

1. They prioritise experiences over assets

Unlike previous generations who prioritised owning a home as a symbol of stability and success, many young people today value experiences over material possessions.

Travel, dining out, and pursuing hobbies are often prioritised over saving for a home.

This shift in priorities means that saving for a deposit may take a backseat to living a fulfilling and flexible life.

2. They have more career mobility and flexibility

Career dynamics have also evolved.

Younger generations are more likely to switch jobs, pursue freelance work, or engage in the gig economy.

This need for career flexibility makes long-term commitments like homeownership less appealing.

The ability to move cities - or even countries - for better job opportunities or personal growth is often more valuable than being tied down by a mortgage.

3. They prefer urban living

Many young Australians prefer the vibrancy and convenience of urban living, which often comes at a higher cost.

Inner-city apartments and rentals provide proximity to work, cultural activities, and social scenes.

For many, the trade-off between owning a suburban home and renting an inner-city apartment is a matter of lifestyle preference.

Renting offers the flexibility to live in desirable locations without the long-term financial commitment of a mortgage.

4. They get married and have children at an older age

There is also a trend of delaying marriage and starting a family.

With fewer young people rushing to settle down, the urgency to buy a home diminishes.

Instead, they are focusing on personal development, career growth, and enjoying their independence.

This delay in family formation naturally postpones the traditional home-buying timeline.

How this lifestyle shift affects Australia's housing market

These lifestyle choices, combined with affordability issues, significantly impact the housing market.

The demand for rental properties, particularly in urban areas, is rising - a shift that has led to a burgeoning market for build-to-rent developments, co-living spaces, and innovative housing solutions that cater to the needs of younger generations.

The property market must adapt to these changing preferences and developers and policymakers need to recognise that the traditional model of homeownership is evolving.

Most importantly, there is an increasing need for affordable housing solutions that offer flexibility and cater to the lifestyle choices of the younger Australian generations.

But there’s a problem

The problem is we’re just not building enough suitable new dwellings.

A recent PropTrack New Homes report revealed data suggesting that government initiatives to meet growing population levels and ease the housing crisis aren’t enough.

In its budget last year the government announced it would encourage the construction of 1.2 million new homes in 5 years.

This year's budget also included plans to incentivise the build-to-rent sector in Australia and increase new rental properties by 150,000 over the next 10 years.

But the Australian Bureau of Statistics recently revealed that our population could reach as much as 36.1 million by 2041 - an increase of 9.7 million people in 20 years - the number of dwellings these government incentives will produce is way off what is actually needed.

For context, the number of households is projected to rise by an additional 4 million, surpassing 13 million, over that timeframe.

But in the past 20 years, the total number of dwellings completed was only 3.4 million, at a time when the population rose by 6.5 million.

This will only continue to put pressure on housing supply reflected in low rental vacancy rates and higher house prices.

At the same time, the strong absorption of new listings for sale has kept total listings in the market suppressed, intensifying competition between buyers.

These factors have created a sharp shortage of housing, outweighing the negative impact of rates on prices.

And there is no end in sight as building approvals (which are a good indication of future supply) are running at very low levels.

And remember, just because a new apartment complex has been approved, it doesn't mean it will get built.

Very few new complexes are coming out of the ground because it's not financially viable to build them at today's market prices.

Of course, this means future new developments will have to sell at prices considerably higher than today’s market value and this will, in turn, pull up the value of established apartments.

A final word…

It’s clear that while affordability issues are a significant barrier to homeownership for younger generations, and thanks to the low supply of affordable housing this will only continue going forward.

But, it's essential to understand that the values and lifestyle choices of young Aussies also play a crucial role.

Today's young Australians are redefining success and stability, often prioritising experiences, flexibility, and urban living over the traditional path of owning a home.

As these trends continue, the housing market must adapt to meet the needs of a generation that values flexibility and experiences just as much as, if not more than, the security of homeownership.

Recognising and accommodating these shifts will be key to addressing the evolving demands of the Australian property market.

The question is, what will our government do to meet these changing needs?