Australia’s leading economists believe Australia can sustain an unemployment rate as low as 3.75% – much lower than the latest Reserve Bank estimate of 4.25% and the Treasury’s latest estimate of 4.5%.

This finding, in an Economic Society of Australia poll of 51 leading economists selected by their peers, comes ahead of next month’s release of a government employment white paper, and an expected direction from Treasurer Jim Chalmers that the Reserve Bank quantify its official employment target.

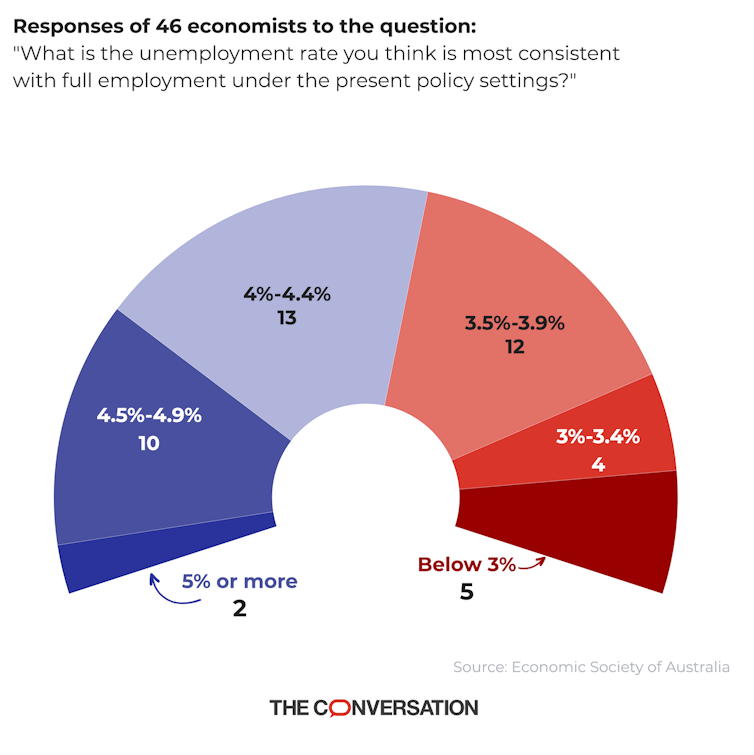

Asked what unemployment rate was most consistent with “full employment” under present policy settings, the 46 respondents who were prepared to pick a number or range picked an average rate of 3.75%.

The median (middle) response was higher, but still below official estimates – an unemployment rate of 4%.

Significantly, only two of the economists surveyed picked an unemployment rate of 5% or higher, which is where Australia’s unemployment rate has been for most of the past five decades.

The 3.75% average implies either that the Reserve Bank and government have lacked ambition on employment for much of the past half-century, or that the sustainable unemployment rate has fallen.

Australia’s unemployment rate dived to 3.5% in mid-2022 and has remained close to that long-term low since.

The survey result suggests the government can lock in the present historic low and need not – and should not – allow unemployment to climb too far from its present rate.

Many of the experts surveyed questioned the idea of a “magic number” or non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) used by the Treasury and the Reserve Bank as a guide to how low unemployment can go without feeding inflation.

Former OECD official Adrian Blundell-Wignall said the concept was not helpful “even in the short run, and certainly not the long run” because NAIRU kept changing depending on what else was going on in the domestic and global economy.

Any rate of unemployment would have a different implication for inflation depending on what the government was doing with tax and spending policy.

Geopolitical events and climate change have probably pushed up the rate of inflation to be expected from any given domestic unemployment rate.

3.5% unemployment, yet falling inflation

Craig Emerson, a former minister in the Rudd and Gillard governments, said NAIRU was best described as the lowest unemployment rate consistent with inflation not taking off. Given Australia’s inflation rate is now coming down, NAIRU is clearly below the present unemployment rate of 3.5%, he argued.

The University of Queensland’s John Quiggin said Australia can be considered to have full employment when the number of job vacancies matches the number of unemployed people. This is the case at present, suggesting “full employment” means an unemployment rate of 3.5%.

Alison Preston from the University of Western Australia said industrial relations changes have given workers much less power to obtain higher wages than before, suggesting the “non-inflation accelerating rate of unemployment” was either lower than before or an irrelevant concept.

Curtin University’s Harry Bloch says there will always be a mismatch between the jobs on offer and the skills available – an academic can’t do the work of a plumber, or vice versa, for instance. But even so, he says it ought to be possible to get unemployment down to the 2% achieved repeatedly during the 1950s and 1960s.

Consulting economist Rana Roy says in normal times “full employment” probably meant an unemployment rate near 1%, but the business cycle meant there would always be brief – “and I stress brief” – periods when governments might have to accept an unemployment rate of nearer 2%.

Fix education, job-matching and childcare

Asked to select the three measures from a list of 11 that would do the most to bring down the sustainable rate of unemployment, the 51 experts overwhelmingly backed improving the quality of school education (55%), followed by improving employment services (39%) and cutting out-of-pocket childcare costs (39%).

There was also strong support for relaxing industrial relations to give employers greater flexibility (33%) and winding back taxes and regulations facing businesses (24%) as well as boosting enrolments in tertiary education (27%).

There was very little support for cutting immigration or the JobSeeker payment.

Labour market specialist Sue Richardson said a high-quality job-matching service would both reduce unemployment and boost productivity because Australians would be matched to jobs for which they were best suited.

The unemployed who would benefit the most would be those further down the queue who were the least successful in finding jobs.

Industry economist Julie Toth said digital technologies and working from home were already making it easier to match Australians with jobs across a range of industries, and it was important to preserve these recent gains.

One of the panellists, Peter Tulip from the Centre for Independent Studies, rejected all the options offered for lowering the achievable unemployment rate, and said the only one that might have some effect was restraint when increasing minimum wages.

Another, Brian Dollery from the University of New England, said much of Australia’s unemployment had been generated by unemployment benefits that were too high.

Together, the results of the survey call for the government and the Reserve Bank to be ambitious about unemployment, and not to accept a rate above 4%.

The government’s employment white paper is due by the end of September.

Individual responses. Click to open:

![]()

Guest Author: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.