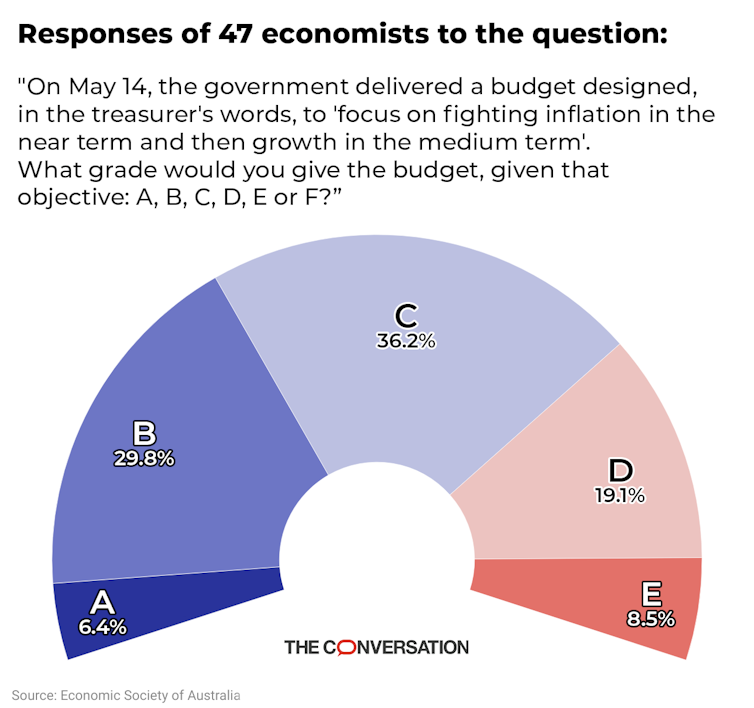

Asked to grade Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ third budget on his own criteria of delivering on “inflation in the near term and then growth in the medium term”, most of the 49 leading economists surveyed by the Economic Society of Australia and The Conversation have failed to give it top marks.

On a grading scale of A to F, 17 of the 49 economists – about one-third – give the budget an A or a B.

Two have declined to offer a grade.

The result is a sharp comedown from Chalmers’ second budget in 2023.

Two-thirds of the economists surveyed conferred an A or a B on that budget.

The economists chosen to take part in the post-budget Economic Society surveys are recognised by their peers as leaders in fields including macroeconomics, economic modelling, housing and budget policy.

Among them are former heads of the Department of Finance, former Reserve Bank board members, and former Treasury, International Monetary Fund, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development officials.

Thirteen of those surveyed – more than a quarter – give the budget a low mark of D or an E.

None have given it the lowest possible mark of F.

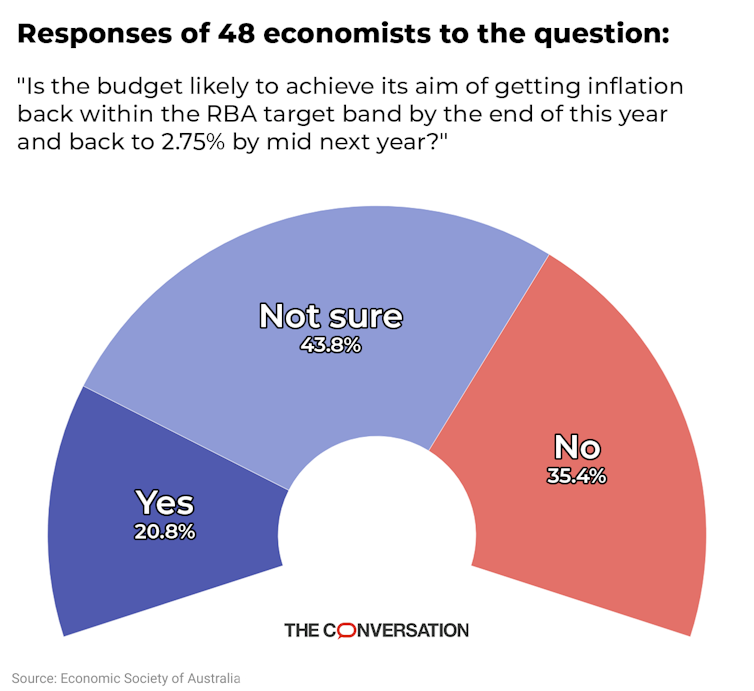

Asked whether the budget was likely to achieve its aim of getting inflation back within the Reserve Bank’s 2-3% target band by the end of this year, and back to 2.75% by mid-next year, 17 thought it would not.

Only ten thought it would.

A greater number – 21 – were not sure.

In his budget speech, Chalmers predicted inflation would come back to the Reserve Bank’s target band sooner than the 2025 expected by the Reserve Bank itself, “perhaps even by the end of this year”.

The budget papers forecast an inflation rate of 2.75% by mid-2025, well within the target band and a half a percentage point lower than the bank’s forecast.

The papers say that there are two measures in the budget that were not known to the Reserve Bank when it produced its forecasts in early May, and explain why the budget forecast is half a percentage point lower.

They are an extra year of energy bill relief of $300 per household and $325 for eligible small businesses and a further 10% increase in the maximum rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

If the lower budget forecast is correct, and if the Reserve Bank sticks to the letter of its agreement with the treasurer that requires it to aim for consumer price inflation between 2% and 3%, the bank is likely to cut interest rates late this year or early next year as inflation approaches its target zone.

But economists including Flavio Menezes from The University of Queensland say while the budget measures might “mechanically” suppress measured inflation, they are:

unlikely to alleviate underlying inflationary pressures and may even exacerbate them; for households not experiencing financial strain, lower energy bills could simply lead to increased spending in other areas.

Former Reserve Bank board member Warwick Mckibbin says the bank is likely to “see through” (ignore) the largely temporary mechanical price reductions and “raise interest rates to where they should be”.

Others surveyed, a minority, argue the economy is too weak for the extra spending in the budget to boost inflation through consumer spending.

Former Finance Department Secretary Michael Keating says any stimulus is “likely to be swamped by the economic slowing well underway”.

Independent economist Saul Eslake said the subsidies for energy and rent would inject only $3 billion into the economy in 2024-25.

This meant any boost they would give to underlying inflation would be hardly “material”.

Tax cuts matter more than energy rebates

More important for boosting the economy would be previously budgeted Stage 3 tax cuts.

These are set to inject $23.3 billion per year from June, climbing to $107.2 billion over four years.

Eslake said the decision to reskew the tax cuts toward middle and lower earners had saved the government from the need to direct extra specific support to these people.

Politically, the government could not have got away with doing nothing.

But Eslake was appalled to discover that the cost of the single biggest spending item in the budget, the untied grants to the states, had blown out even more than expected.

The special top-up for Western Australia is now set to cost $53 billion over 11 years instead of the $8.9 billion over eight years expected in 2018.

How the national government could justify gifting $53 billion to the government of Australia’s richest state was beyond his comprehension.

Big issues unaddressed

A repeated theme among the economists was that the budget did very little to boost productivity or address persistent problems.

Several described it as an election budget, others a budget driven by polling.

Macquarie University’s Lisa Magnani said the lack of attention to home prices, the funding of public schools and the poor performance of Australian firms was concerning, given Chalmers’ claim it was a budget for “decades to come”.

Former Department of Foreign Affairs chief economist Jenny Gordon said the budget had failed to tackle the distortions in the housing market and the financial sustainability of needed services including health care, aged care and childcare.

Independent economist Nicki Hutley said crunch time for tax reform was coming, given the large baked-in increases in spending on defence, health and disability insurance and Australia’s over-reliance on income tax and company tax.

Warwick McKibbin said Australia’s main economic problems were its lack of productivity growth, the big changes needed to bring about the energy transition, the surge in artificial intelligence, the risk of much lower export prices and geopolitical uncertainty.

The government should have tried to build a bipartisan consensus about how to fix these.

Private investors were hanging back knowing that whatever the government did could be reversed at the next election.

Although many of those surveyed welcomed the Future Made in Australia Act, some criticised its approach of “picking winners” and “wasting precious resources” by putting money into activities such as the manufacture of solar panels, which could be done more cheaply elsewhere.

Bigger government

Former Industry Department chief economist Mark Cully said it was in some ways one of the most consequential budgets in years.

It locked in a clear shift towards higher spending and revenue, which, at around 26% of GDP, was higher than any other time Australia had been near full employment.

Future Made in Australia was the most marked intervention by a government in shaping the future direction of the economy for decades.

Guest author is Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.