The vast arsenal of fiscal, monetary, and legal measures used by Australian governments to offset the COVID-induced economic crisis have worked well.

They did not prevent a recession (popularly defined as two-quarters of negative GDP growth) but things could have been much worse.

What is particularly interesting is that the expected consequences have not shown up in the official statistics for financial distress – insolvent companies entering administration and individuals declaring bankruptcy.

Indeed, a misleading impression of 2020 being one of “economic good times” could be gained from the statistics.

The big question is whether these statistics show government relief measures have averted economic pain or simply deferred it.

As measures are wound down and withdrawn, will the private sector be willing and able to pick up the resulting slack?

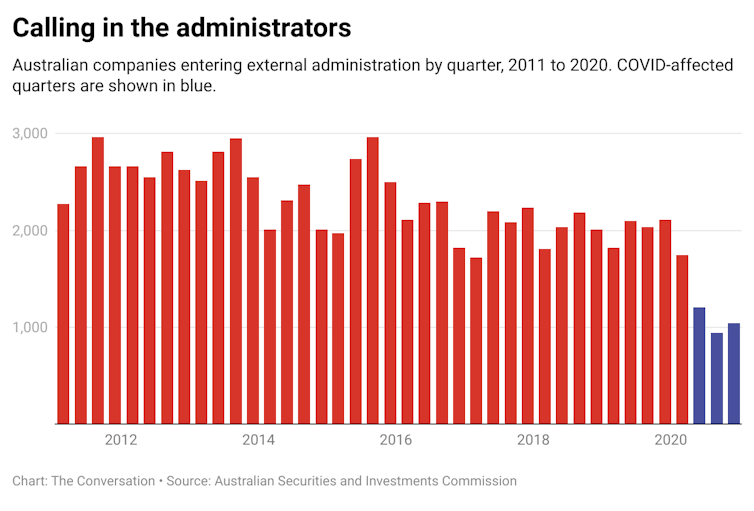

Companies entering administration

There are, of course, “lies, damn lies, and statistics”.

The figures hide what is likely to be actually happening in terms of financial distress.

Impacts on businesses and individuals have been quite varied.

Some large corporations have come through in good shape, much better than might have been imagined.

But the tourism, hospitality, entertainment, and higher education sectors have taken significant hits and face an uncertain and drawn-out recovery.

The following graphic, using data from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, shows the number of companies entering external administration (quarterly from 2010 to 2020).

Notable is the decline in business collapses in 2020 – the opposite of what one would expect in a time of economic stress.

A number of policy actions contributed to this.

The most obvious contributors to keeping failing businesses alive were JobKeeper payments as well as changes increasing “safe-harbour protections” to reduce the risk of prosecution for trading while insolvent.

These changes also reduced the ability of creditors to speedily force a debtor company into insolvency.

In many cases it is quite possible these simply put off that day to some time in 2021.

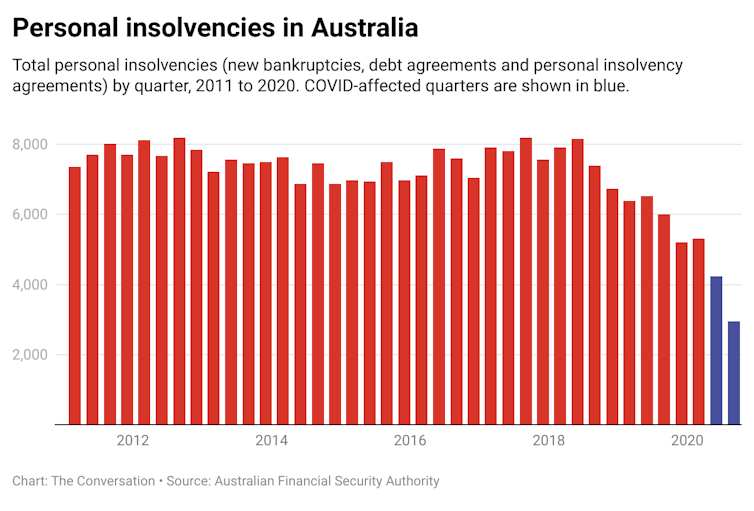

Individuals declaring bankruptcy

At the personal level, which includes owners of small unincorporated businesses, a similar pattern can be seen.

The next graph uses data from the Australian Financial Security Authority.

It shows the number of individuals entering into insolvency (bankruptcy, debt agreements etc) on a quarterly basis.

The latest data is for the September quarter of 2020.

The number had fallen to about half of what it had been prior to 2020.

Notably, the number of personal insolvencies began falling in early 2018.

There is no obvious single explanation for this trend, though good economic conditions and low interest rates are probably part of the story.

The further decline in 2020 (in contrast to expectations of an increase) is most likely due to legislative changes introduced in March 2020 and extended in September 2020.

These include increasing the size of debt owed before a creditor can initiate action from A$5,000 to A$20,000, and allowing debtors six months (rather than 21 days) to respond to creditor demands. Mortgage repayment deferrals by banks also would have helped.

A difficult balancing act

What to make of these unexpected declines in official indicators of financial distress when economic conditions have surely increased the reality?

The more optimistic interpretation is that various government support measures have prevented both business and individuals sliding into insolvency.

The less optimistic interpretation is the measures have simply deferred the final outcome – with the statistics soon to show a bounce in business failures and personal insolvencies.

There is no point keeping “zombie” businesses alive, nor in dissuading heavily indebted individuals from taking action under insolvency arrangements that can give them a fresh start.

But finding the right balance of continuing support for recoverable cases while terminating it for others (and limiting the hardship caused by failure) is a difficult and challenging task for our economic masters.

Kevin Davis, Emeritus Professor of Finance, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.