Key takeaways

The structure of our housing system, politically, economically, and culturally, is built to favour rising house prices.

Homeowners, investors, lenders, and those in property-related industries have gained significantly.

But renters, first home buyers, key workers, and younger Australians are increasingly being priced out, widening the wealth gap and putting the future of the middle class at risk.

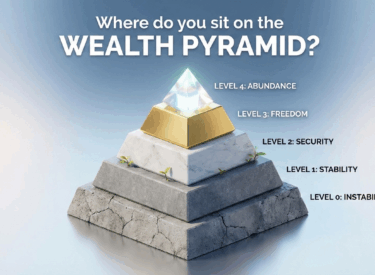

Rising prices have shifted Australia from a bell-curve, middle-class society to a U-shaped one, with larger groups at either end of the wealth spectrum.

This has social, economic, and political consequences, especially as generational divides widen and home ownership becomes less attainable.

A sharp fall in house prices would damage confidence, banking stability, and the economy.

Instead, policies should aim for house price growth that is slower than wage growth, allowing affordability to improve gradually and sustainably over decades.

Despite these challenges, property remains the most effective long-term wealth-building tool for Australians.

Investors should focus on fundamentals, not fear, and play the long game, backed by strategy, not speculation.

For as long as most Australians can remember, rising property values have been seen as a good thing.

Something to aspire to. A source of security. A sign of success.

When your home is worth more today than it was last year, you feel a little wealthier.

Banks are more willing to lend. You might borrow against your equity. You spend more freely. You feel like you’re getting ahead.

Politicians, banks, and everyday homeowners have grown comfortable, if not addicted, to this rising tide of property wealth.

But it’s time we asked a more uncomfortable question: Do we actually want house prices to keep going up?

And if so, who really benefits, and who gets left behind?

This is a question Simon Kuestenmacher and I explored in a recent conversation on Demographics Decoded podcast.

Together, we unpacked the deeper structural forces behind Australia’s housing market, and why its long-term trajectory is largely a result of deliberate policy choices, not chance.

Because as Simon pointed out: "house prices aren’t an act of God; they’re a reflection of political will and economic design."

For weekly insights subscribe to the Demographics Decoded podcast, where we will continue to explore these trends and their implications in greater detail.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player:

A system designed for rising prices

Let’s start by acknowledging something that rarely gets said out loud: the Australian property market is engineered, intentionally or not, for prices to rise.

And it’s not hard to see why.

As Simon notes, the language we use around house prices gives the game away.

When prices fall, we say the market is crashing. When they rise, we say it’s recovering.

There’s an embedded assumption that higher is better, and that prices should keep rising indefinitely.

Of course, if you already own property, that narrative suits you just fine. And that group of Australians is substantial.

The many beneficiaries of price growth

Simon laid out a long list of winners in this system, and it’s possibly even longer than you might think.

1. Homeowners and investors

This one’s obvious. When property prices rise, so does the net worth of those who own them.

It becomes easier to refinance, borrow, or leverage into additional investments. It’s the foundation of intergenerational wealth in Australia.

2. Banks and lenders

More expensive homes mean bigger mortgages.

And since most Australian banks generate the bulk of their profit from home loans, rising prices are great for business.

Longer loan terms and larger principal amounts translate into more revenue.

3. Governments at every level

Stamp duty, land tax, and capital gains taxes are all tied to property values.

In fact, some state budgets are now dangerously reliant on housing revenue.

The federal government is also now deeply entangled, offering shared equity schemes and loan guarantees.

As Simon pointed out, "Governments are no longer just regulators of housing, they’re investors too."

4. Superannuation funds

Whether directly through real estate holdings or indirectly through listed property trusts, rising property prices are a boon for large super funds and, by extension, for millions of Australians with a super balance.

5. Construction and renovation sector

Builders, tradies, architects, engineers, when property prices are rising, so is demand for their services.

People renovate, extend, or knock down and rebuild. That flows through to the broader economy.

6. Retail and Lifestyle Businesses

Feeling wealthier on paper affects our behaviour.

From buying designer furniture to installing luxury tapware, Simon notes that "the richer you feel, the more likely you are to buy the fancy Danish version rather than the knock-off alternative."

7. The media

The property market is a perennial news driver.

Rising prices sell hope. Crashes sell fear.

Either way, it keeps eyeballs glued and advertising dollars flowing.

8. Even local councils

Council rates are tied to property values.

The higher the valuation, the more they can extract.

It’s a quiet but powerful part of the system.

In short, a huge chunk of the economy, from tradies to treasurers, has a vested interest in rising house prices.

And yet… there are losers too

While the system works well for those who already own property, it’s creating mounting pressure for those who don’t.

Simon bluntly said:

“The rising cost of housing is creating structural inequality. It’s reshaping who gets to build wealth, and who doesn’t.”

Here’s who’s being squeezed:

1. First home buyers

The most obvious group - as prices rise faster than wages, younger Australians are struggling to break into the market.

Saving for a deposit takes longer. Repayments eat up more income.

The dream of home ownership is slipping further out of reach.

2. Renters and low-income households

As investors pass on higher mortgage costs through rent increases, more Australians are experiencing rental stress.

The portion of income needed just to keep a roof over one’s head is rising, especially in our capital cities.

3. Essential workers

Nurses, teachers, police, aged care workers, those in key community roles often can’t afford to live near where they work.

This leads to long commutes, fatigue, and reduced community engagement.

4. The shrinking middle class

We’ve long prided ourselves on being a middle-class society.

But Simon warns we’re transitioning into a U-shaped society: a growing number of asset-rich on one side, and a growing number of asset-poor on the other, with fewer people in the middle.

“We still think of ourselves as a fair-go country,” he said, “but we’re no longer shaped like a bell curve. That middle is vanishing.”

5. Government budgets (Ironically)

Yes, they benefit from rising prices via taxes, but they also face ballooning costs: more funding needed for social housing, rent assistance, mental health services, and even foster care, which sees demand rise as housing stress increases.

6. The broader economy

When too much capital is funnelled into residential property, there’s less left over for innovation and productive investment.

Our stock market remains undercapitalised compared to global standards.

So what can be done?

Note: Let’s be frank, affordability is not a bug in the system. It’s the outcome of deliberate design.

Rising house prices are the goal, not a side effect and changing that would require political courage that’s rarely seen.

Simon floated a few policy ideas that could ease affordability over time:

-

Replacing stamp duty with a broad-based land tax.

-

Abolishing first-home buyer grants that inflate prices.

-

Loosening zoning restrictions to increase density in middle suburbs.

-

Halting schemes like super-for-housing that pull forward demand.

But as he also noted, “Any party that proposes policies to bring down house prices loses the next election.”

So, should we want house prices to fall? Not suddenly.

That would be catastrophic, risking bank collapses, recession, and consumer panic.

Simon argues:

“What we really want, is a slow, strategic retreat. We want house price growth to track below wage growth for a long period. That would gradually improve affordability without tanking the system.”

It’s a vision of slow recalibration, not market destruction. And while politically difficult, it’s economically sound.

The long game still belongs to property

Despite these tensions, I still believe strongly that property remains the most reliable vehicle for building wealth in Australia.

There will always be cycles. Ups and downs. Government tinkering.

But the fundamentals: strong population growth, land scarcity in key areas, lifestyle desirability, remain intact.

Yes, we need reform. But no, the system is not about to change overnight.

So, if you’re a property investor or a homeowner, don’t feel guilty that you’ve done well.

You made a decision, took on risk, and were rewarded. That’s capitalism.

But also recognise that a sustainable market is one where more people, not fewer, have a fair shot at getting in.

Final thoughts

We don’t need the most expensive property market in the world.

What we need is a functioning one in which capital growth is steady and sustainable, where young Australians can see a path forward, and where the middle class can thrive.

As I often say, don’t make 30-year investment decisions based on the last 30 minutes of news.

Be strategic. Think long term. Get the right advice.

Because playing the long game is what successful investors do, and property remains the best game in town.

For weekly insights, subscribe to the Demographics Decoded podcast, where we will continue to explore these trends and their implications in greater detail.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player: