Key takeaways

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has unveiled a new cap on high debt-to-income (DTI) lending – a move designed to keep a lid on riskier borrowing as the housing market gathers price momentum, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne.

APRA’s new cap limiting banks to 20% of loans at DTI ≥ 6 isn’t binding today.

Most lenders are already well below that level, so borrowing power and credit availability remain essentially unchanged.

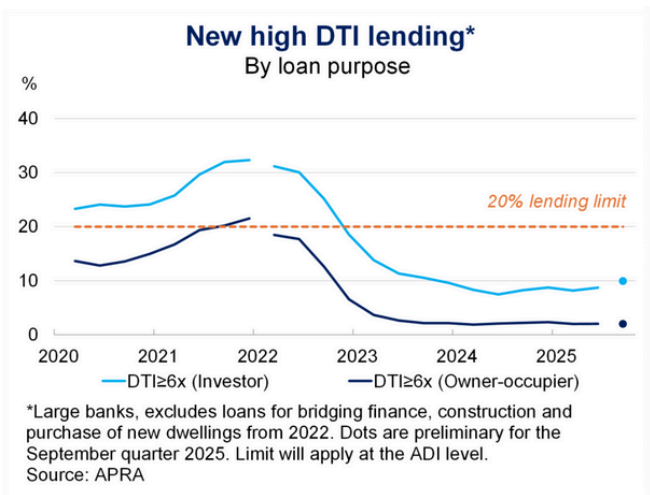

APRA is stepping in early because investor high-DTI lending has edged up from historic lows.

If the market heats up further, the cap will automatically slow riskier borrowing, a proactive move rather than a reactive crackdown.

High-DTI lending is most common among investors. If activity pushes close to the cap in the future, banks may tighten criteria or increase pricing for this segment, cooling demand at the margins.

APRA has carved out lending for new builds and new dwellings, and FHBs rarely borrow above six times income.

Importantly, this policy won’t change the structural drivers of prices: population growth, rental shortages, and supply constraints.

With credit conditions unchanged and interest rate cuts expected to be slow and limited, this is simply good housekeeping.

Smart investors can continue to move with confidence, knowing the regulator is smoothing out risks early in the cycle.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has unveiled a new cap on high debt-to-income (DTI) lending – a move designed to keep a lid on riskier borrowing as the housing market gathers price momentum, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne.

From February 1, 2026, banks will be restricted to issuing no more than 20% of new loans at six times a borrower’s income or higher, with separate caps for owner-occupiers and investors.

Now this doesn't really come as a surprise to me...every property cycle has a moment where momentum starts to build, confidence lifts, and borrowing appetites quietly stretch a little further.

Right now, we’re entering one of those phases.

Prices are rising again in Sydney and Melbourne, credit growth has ticked above long-term averages, and lower rates have helped buyers push their borrowing capacity a touch higher.

It’s at these turning points, when optimism grows faster than caution, that regulators tend to step forward.

APRA has just done exactly that.

At face value, it sounds like a major tightening.

But according to Domain’s Chief of Research and Economics, Dr. Nicola Powell in practice, the limit is not currently binding, meaning it won’t change borrowing power for most buyers.

She explains that it is best understood as early intervention: a guardrail being put in place before lending standards begin to loosen.

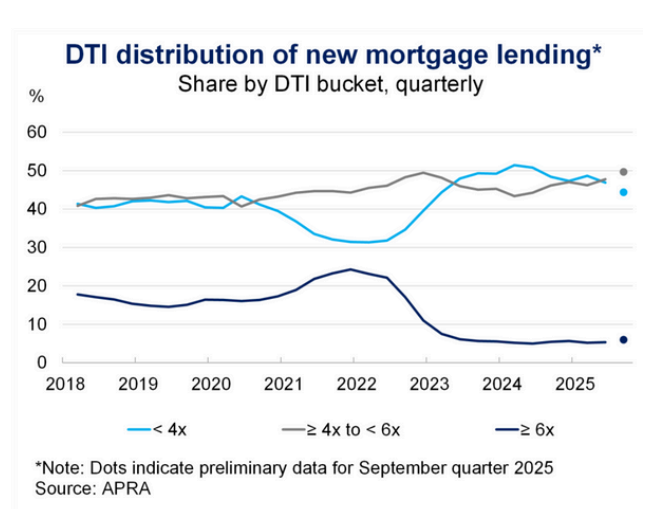

And, crucially, it comes at a time when overall lending standards remain solid – if anything, less risky than several years ago.

A subtle move designed for an early stage in the cycle

The new cap isn’t a ban. Banks can still issue high-DTI loans; they simply can’t let those loans exceed 20% of their new lending for owner-occupiers and investors.

Crucially, most lenders are already well below that threshold.

According to APRA, high-DTI lending remains well below the new 20% cap, with recent data showing around 10% of new investor loans and less than 5% of overall new lending written at six times income or higher.

In other words, the limit isn’t binding today. And because of that, it won’t suddenly change borrowing power or dampen demand.

As Dr. Nicola Powell notes:

"It’s a guardrail, not a circuit breaker, something APRA is putting in place before lending standards loosen later in the cycle.

This is a proactive macro-prudential management: shaping risk before it accumulates."

According to Domain, APRA’s decision fits neatly into the broader macro environment:

-

Borrowing capacity has risen

-

Price momentum has returned in major capitals

-

Investor appetite is strengthening

-

But interest rate cuts from here are expected to be smaller and slower

Because markets no longer expect a rapid series of rate cuts, there’s less risk of a sudden surge in borrowing power, which means the cap is unlikely to "bite" quickly.

Dr Powell explains...

What the cap does do is create a mechanism that automatically slows high-risk lending if it accelerates.

If the market heats up and high-DTI loans surge as they have in past cycles, the limit will start to constrain activity.

This approach allows APRA to act preemptively while avoiding the disruption of a sudden clampdown.

The design is deliberate. The limit:

- Targets investors and owner-occupiers separately, allowing APRA to focus on where risk is emerging.

- Excludes lending for new construction and new homes, ensuring the policy doesn’t hold back housing supply.

- Sits alongside existing safeguards, including the 3% serviceability buffer and APRA’s counter-cyclical capital buffer.

It’s a measured and targeted tool rather than a blunt restriction.

What smart investors should take from this

Dr Powell further explains:

Importantly, this is not a policy designed to steer house prices.

It won’t alter the structural forces driving the market: strong population growth, tight rental conditions, limited construction capacity and an ongoing shortfall of new housing.

The carve-out for new dwellings reinforces the point – APRA is careful not to constrain development at a time when Australia needs more homes

In other words...this move reinforces several points seasoned investors already understand:

1. Credit remains the cornerstone of every cycle.

When APRA signals its focus on high-DTI lending, it tells you exactly where pressure could build later, and where borrowing conditions could tighten first.

2. Investors will be the first to feel any future tightening.

Not today, but down the track if high-DTI lending rises.

This is a familiar pattern from previous macro-prudential cycles.

3. Supply, not credit policy, will continue to drive prices.

APRA is not addressing construction constraints, population growth, rental shortages, or under-building, all of which keep upward pressure on prices.

4. Early-cycle opportunities remain intact.

Because this rule isn’t binding yet, borrowing conditions haven’t changed.

Savvy investors with strong serviceability and buffers can still move decisively.

So where does this leave us?

APRA’s cap on high-DTI lending is best thought of as a seatbelt, not a speed limiter.

It keeps risk in check without slowing the market. And it’s perfectly timed for a phase where confidence is returning but exuberance hasn’t taken hold.

I imagine that some investors who rely on stretching their borrowing capacity will try to secure loans ahead of the new restrictions coming in and this could lead to a short-term surge in property demand.

However, in the long term, for serious property investors this is a constructive development.

The system remains stable. Lending remains available. And opportunities continue to emerge for those who understand the interplay between policy, credit and cycles.

As always, the investors who will have the edge are the ones who read the environment early… and act strategically.