If you’re paying off a mortgage – or aspiring to – imagine if you didn’t have to worry so much about rising interest rates.

That’s already the reality for US home buyers.

Unlike in Australia, most mortgages in the US have a fixed-interest rate, locked in for 30 years.

Instead of having to wait and see if their central bank (the Federal Reserve) raises rates each month, a US 30-year fixed mortgage at 2% will still have the same monthly repayment – even after a rate rise.

In contrast, when the Reserve Bank of Australia lifts rates it has huge implications for household budgets, because most borrowers still have variable-rate mortgages.

Every time the cash rate increases and banks inevitably pass through that increase, our mortgage payments go up too – adding thousands of dollars to average annual repayments.

This is one reason why RBA governor Philip Lowe has been so cautious about following the US Federal Reserve’s strong signal about lifting interest rates.

So why don’t Australian lenders offer 30-year fixed-rate mortgages too, like their US counterparts?

Every extra 1% can cost thousands

Here in Australia, an extra 1% on a A$600,000 mortgage means $6,000 a year more in interest payments.

And these are post-tax dollars.

So if you earn $100,000 and hence pay an average tax rate of 25%, that’s like taking a roughly $8,000 pay cut.

Ouch.

A 3% rise in official rates over two to three years is not impossible.

On a $600,000 mortgage that would mean an extra $18,000 a year in interest payments.

The RBA knows this, of course.

It looks at Australian household debt of more than 120% of GDP and knows raising rates too aggressively risks putting a significant number of Australian households into financial distress.

In one sense this is good news.

It means the RBA has large-calibre ammunition to fire in pursuit of its monetary policy goals (to keep unemployment low and inflation between 2% and 3%).

But it would be better if the Australian mortgage market involved less risk for consumers.

There is no reason why Australian lenders couldn’t offer 30-year fixed-rate mortgages.

After all, there’s an active government bond market with maturities from one year to 30 years. This provides a benchmark to price mortgages.

Two fixes for more affordable mortgages

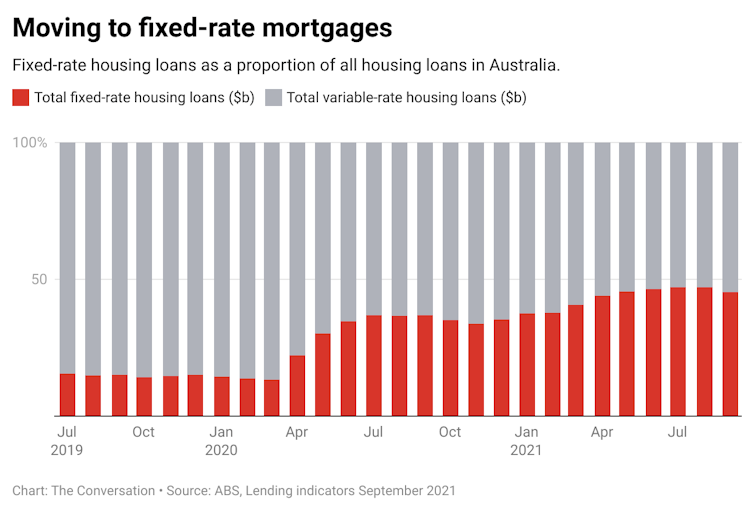

Fixed-rate mortgages have become much more popular in Australia in the past few years: the proportion of new mortgages that were fixed jumped from about 15% in June 2019 to more than 45% by September 2021.

But even those loans are typically fixed for only three years – sometimes as short as one year, sometimes as long as five years.

After that, the rate reverts to the variable rate.

Longer fixed-rate loans would insulate Australian borrowers from big swings in interest rates.

In the US you can refinance a 30-year fixed mortgage if long-term rates drop.

So you benefit if rates go down but are protected if they go up.

Another idea to improve loan contract terms for borrowers – long advocated by University of Melbourne economist Kevin Davis – is the so-called “tracker mortgage”.

These contracts limit borrowers to paying a certain “spread” over a benchmark interest rate.

Such offerings depend in large part on competition in the banking sector.

The US has lots of competition in banking.

Australia has very little.

When costs go up, two groups can bear that cost: customers or shareholders.

In Australia when bank funding costs go up, customers bear pretty much all of the cost, and shareholders zero.

That’s the best evidence you’ll ever get of true market power.

Threading the needle

The Reserve Bank is well-positioned to drive the official unemployment rate down from 4.2% to the lowest levels in 50 years while keeping inflation under control.

It knows when it does increase interest rates this will transmit very directly to the real economy.

The challenge for Lowe is to use his interest-rate firepower in true Goldilocks fashion: not too little but not too much.

That will be the great central banking challenge of the next several years.

If we could restructure the Australian mortgage market to better protect borrowers from swings in interest rates, the job of future RBA governors need not involve such a delicate balancing act.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.