Key takeaways

Australia’s homeownership rate is sliding. From ~¾ of households in 1996 to 63% by the 2021 Census, with the steepest falls among under-45s.

Affordability—not renting per se—is the core issue. Entry barriers (deposit + serviceability) are at modern highs despite more people renting.

Why homeownership matters: it’s the strongest predictor of retirement security, anchors belonging (“owning a small piece of the country”), and historically underpins a broad middle class and political stability.

Outlook without change: overall homeownership could drift below 60% in coming decades; headline rates may blip up as millennials age-in, but youth ownership keeps falling.

Bottom line: Australia must choose—preserve broad-based ownership and social cohesion through steady, pragmatic reforms, or accept a narrower “owners’ club.” It’s a dream worth fighting for.

For decades, owning a home has been the cornerstone of the great Australian dream.

It has symbolised not just financial security, but also stability, belonging, and a pathway to wealth creation.

But that dream is slipping away for many Australians.

In 1996, nearly three-quarters of Australian households owned their own home.

By the 2021 Census, that figure had fallen to 63%. Among younger Australians, the decline is even more dramatic.

While renting has become more common, the real issue is affordability.

The barriers to entry into homeownership have never been higher, and this shift has wide-reaching consequences for individuals, families, and the nation as a whole.

For weekly insights subscribe to the Demographics Decoded podcast, where we will continue to explore these trends and their implications in greater detail.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player:

Why homeownership matters

A home is more than just bricks and mortar.

It represents security, a sense of place, and a foundation for building wealth.

As Simon Kuestenmacher explains in our latest Demographics Decoded podcast:

“Owning a home gives you a sense of belonging. It literally means you own a small part of the country and feel more invested in its ups and downs.”

It’s also the single best predictor of financial security in retirement.

Renters who face ongoing housing costs late into life are left vulnerable to poverty.

Homeowners, in contrast, can live mortgage-free and enjoy greater independence.

And on a societal level, high rates of homeownership have historically underpinned a strong middle class, political stability, and a sense that the system works for ordinary Australians.

When homeownership falls, it risks fraying those bonds.

Looking back: the era of peak homeownership

To understand today’s decline, we need to rewind to the mid-20th century.

After World War II, returning servicemen were actively encouraged to enter homeownership.

Government-backed housing schemes and subsidies, along with affordable land on the urban fringe, enabled families to purchase modest homes on a single income.

By the 1960s, house prices were only three or four times the median income.

As Simon notes:

“That was very much affordable. Everything worked in favour of getting the homeownership rate up.”

Even young adults in their early 20s could enter the market, a life stage traditionally reserved for renting.

That affordability created what demographer Bernard Salt famously called “Peak House”, a time when nearly three-quarters of Australians owned their home.

Why homeownership has declined

Several forces have eroded this once high rate of ownership:

- House prices outpacing wages

Since the 1980s, property values have grown far faster than incomes. While wages crept up gradually, housing costs skyrocketed. The gap between what Australians earn and what they need to spend on housing has become a chasm.

As Simon put it: “In the gap between money earned and money needing to be spent on a house, things just kept getting worse.”

- Stricter lending standards

Banks today require higher deposits and stricter serviceability checks. While financially sensible, it has made saving for a deposit increasingly difficult, especially as rents rise and eat into household savings. - Tax policies favouring investors

Negative gearing and capital gains tax discounts have encouraged investors into the market, competing directly with first-home buyers. This has tilted the playing field away from aspiring owners. - Planning and supply issues

Complex planning systems, delays in approvals, and insufficient state-built housing have constrained supply. At the same time, Australia’s strong migration program has driven demand, particularly in major cities. - Cost pressures in construction

Shortages of skilled trades, rising material costs, and the risks faced by developers (many operating on razor-thin margins) have further reduced the flow of new, affordable housing.

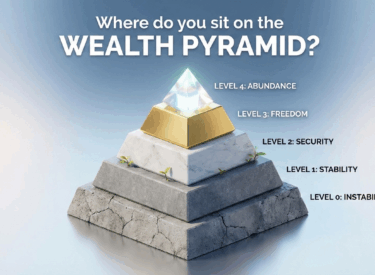

The wealth divide: owners vs renters

The decline in homeownership is more than just a statistic. It’s reshaping Australian society.

Homeowners build wealth over time and often pass it down to their children.

Renters, on the other hand, risk being permanently locked out of the wealth escalator.

As Simon warned:

“On average, the vast majority of wealth in Australia sits in the shape of a house. If that isn’t there, the gap between owners and renters will continue to increase, creating intergenerational inequity.”

This divide means children of homeowners inherit property and financial security, while children of renters inherit little.

Over time, this risks creating a two-tier society.

Political and social implications

Falling homeownership also has political consequences.

Renters and owners often vote differently, and frustration among younger generations is already reshaping the political landscape.

Simon observes:

“Essentially, everyone under the age of 45 tells us in surveys that they hate Labour and Liberal, that they hate the major parties.”

As more Australians are locked out of homeownership, we can expect increasing support for minor parties promising housing reform.

Meanwhile, governments remain reluctant to make housing cheaper, fearing a backlash from existing homeowners who want property prices to keep rising.

What can be done?

There’s no single fix, but a range of policy shifts could help:

- Encourage medium-density housing near transport hubs and employment centres, making better use of land.

- Rebuild public housing through a state-owned developer, ensuring affordable stock is available where the private sector won’t deliver.

- Reform tax settings so they don’t disproportionately favour investors over first-home buyers.

- Streamline planning approvals to accelerate new supply without compromising quality.

- Invest in training skilled workers to ensure construction can keep pace with population growth.

As Simon points out, we don’t need radical disruption:

“I would always urge for slow, gradual policy shifts rather than any kind of major, crazy disruption. I want evolution rather than revolution.”

The Road Ahead

Without change, homeownership rates could slip below 60% in the coming decades.

While the overall rate may briefly rise as millennials age into ownership, the proportion of younger Australians owning homes is likely to keep falling.

That matters because homeownership underpins not just individual wealth, but also social stability, political confidence, and economic resilience.

When people buy homes, they buy furniture, appliances, and services, spending that fuels the wider economy. When they can’t, everyone feels the impact.

The story of Australian homeownership isn’t finished yet.

The choices we make today, through policy, through voting, and even through how we invest, will determine whether the dream of owning a home remains within reach for future generations, or whether it becomes an exclusive club.

And as I see it, that’s a dream worth fighting for.

If you found this discussion helpful, don't forget to subscribe to our podcast and share it with others who might benefit.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player: