During the COVID-19 pandemic years, our government battled to keep the economy in growth despite lockdowns and border closures by creating massive amounts of new money.

We are now experiencing the legacy of this strategy in the form of higher interest rates, inflation and rising housing prices.

At the onset of the pandemic, most economists and analysts believed that lockdowns and border closures would send our economy into recession.

Huge fiscal stimulus packages were rolled out, designed to keep the economy ticking along until the crisis was over.

The government pumped one trillion dollars of newly minted money into the economy, created by and then borrowed from the Federal Treasury at historically low-interest rates.

The resulting relief schemes gave welcome financial support to workers and businesses and while much of this largesse was deemed necessary, our economy is now awash with nearly one trillion worth of dollars that didn’t exist before the pandemic.

This time it was going to be different

Printing more money has always led to higher inflation, but this time, the experts assured us, the huge amount of “quantitative easing”, (which is what economists call money printing) would not lead to inflation.

The reason was that it was designed to keep the economy in growth, rather than generating more spending power.

Although we were assured it would be different this time, basic economics dictates that creating money causes more demand.

Without more supply, inflation is the result.

The trillion dollars of new money washing around our economy will continue to generate inflation until inflation itself slows down the level of demand.

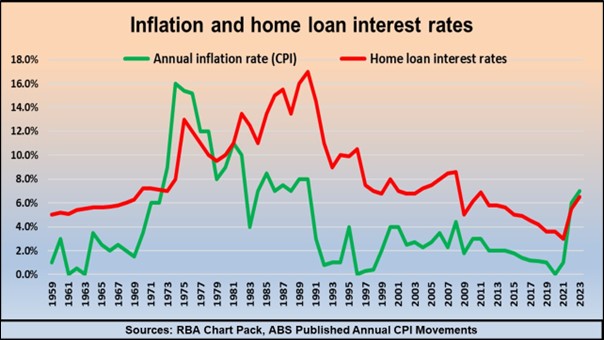

Since its creation in 1959, the Reserve Bank’s mantra has been to control inflation, but its only tool is the cash rate, which sets benchmarks for home loan interest rates.

This means that whenever inflation rises, interest rates follow.

Right now, these two unwelcome newcomers are once again impacting the property market, but what is the likely outcome for housing prices over the next few years?

Inflation and housing interest rates are linked

The Reserve Bank has always used interest rates to control inflation, and the first graph shows how this has led to home loan interest rates and inflation being closely linked since the Reserve Bank was created in 1959.

You can also see that interest rate movements have tended to lag behind inflation changes by at least a year.

The lag in interest rate rises shows how the Reserve Bank has reacted to changes in inflation rather than trying to anticipate them – except for the last nine rate rises.

This time around, interest rate rises have coincided with increases in inflation.

- Also read:Melbourne property market forecast for 2026 | Is it a good time to invest in Melbourne?

- Also read:Latest Property Price Forecasts Revealed. Australian Property Market Outlook 2026: Where To Now After The Rate Rise.

- Also read:Brisbane Property Market Forecast [2026] – What’s Ahead & Where to Invest

- Also read:Sydney property market forecast for 2026. Is it a good time to invest in Sydney?

- Also read:Booming Housing Markets Rise Over February | Latest stats from Dr. Andrew Wilson

This could mean that the bank believes that interest rates are far too low, or it may be that the RBA expects inflation to rise more quickly than previously anticipated, or it could signify both.

The graph also demonstrates that since the nineteen seventies, home loan interest rates have always been higher than the prevailing inflation rate – except for right now.

This also means that interest rates may rise further, at least until the rate of inflation reduces.

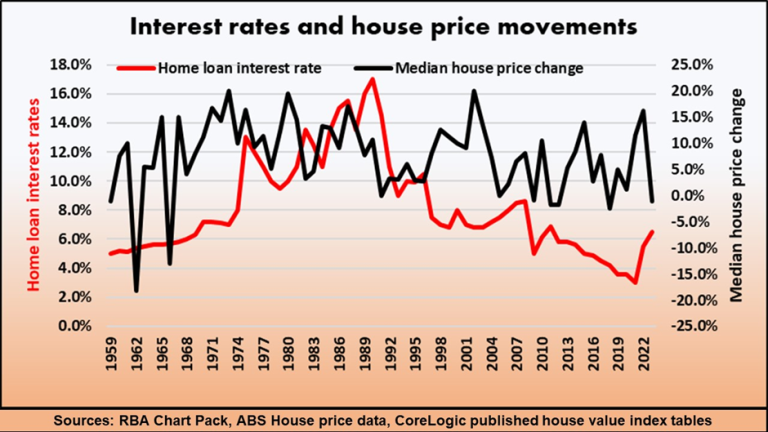

Interest rates have never had a long-term impact on housing prices

This next graph shows that higher interest rates, which at times exceeded thirteen per cent during the seventies and eighties, had no negative impact on house prices.

In fact, even during the worst periods of high-interest rates, housing prices rose annually by ten per cent and more.

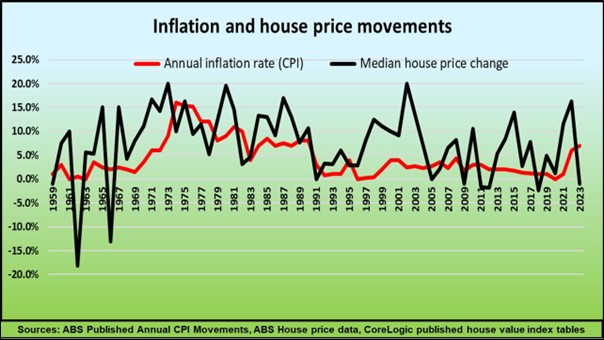

The reason for this apparent contradiction is that housing prices are influenced by inflation significantly more than they are by interest rates.

The next graph shows the close correlation between inflation and house price movements.

The reason for this is that inflation affects all households, whether they are homeowners, renters or potential buyers, but only a small percentage of households are seriously impacted by higher interest rates.

One-third of our dwellings are fully owned without any mortgage, while another third are owned by investors who can claim interest costs as a tax deduction and can also recoup them from tenants by periodically increasing the rent.

According to the ABS, the total value of mortgage debt is only twenty per cent of the value of all residential property and only around ten per cent of homeowners are recent buyers who are now paying higher interest rates than when they purchased their homes.

This explains why interest rate movements normally don’t play a large part in house price changes but also prompts us to ask why the recent rises in interest rates have led to housing price falls.

How the housing market is likely to perform over the next few years

The reason that housing prices have been falling in many locations is that the market is in a state of shock after we were assured that there would be no rate rises until this year, and were then slugged with a record number of consecutive interest rate rises.

This has led to a widespread fall in buyer confidence, even in areas where most buyers are investors, upgraders or downsizers and as such, are relatively immune from rate rises.

This pessimistic outlook will quickly dissipate once interest rates stabilise in future.

In coming years, house prices are far more likely to perform in line with inflation, along with other goods, services, incomes and outgoings.

As far as the property market is concerned, higher inflation will lead to higher housing prices and this will become the most enduring legacy of the pandemic.