Key takeaways

The RBA is clear: international students were not a major driver of the post-pandemic surge in rents or inflation.

Much of the rental price growth happened before borders reopened, meaning the student return wasn’t the trigger.

Years of under-building, planning delays, and investor fatigue have left Australia with chronic undersupply.

International students may concentrate demand in specific areas (inner-city hubs), but they’re not the root cause.

There’s been no shortage of finger-pointing when it comes to Australia’s rental crisis.

One of the more popular scapegoats in recent years? International students.

After all, when you have hundreds of thousands of students flooding back into the country after the pandemic, it’s easy to assume they’d be pushing up rents, tightening supply, and even fuelling inflation.

But according to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s latest Quarterly Bulletin, as reported by ABC news, that narrative doesn’t stack up.

Their analysis suggests international students played only a minor role in the post-pandemic surge in rents and inflation.

Let’s look at what the RBA actually said, and what it means for property investors, policy makers, and the broader housing conversation.

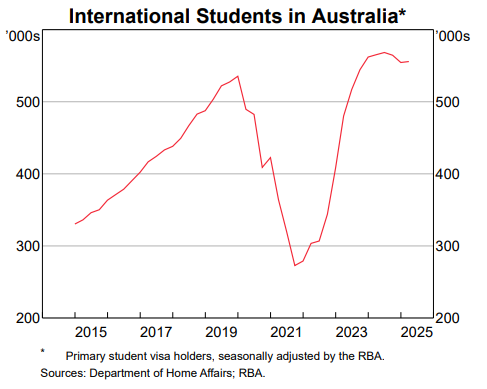

Yes, student numbers surged, but timing matters

There’s no denying the numbers are big.

In 2022, there were just under 300,000 international students in Australia.

By the end of 2023, that figure had ballooned to 560,000.

Source: RBA

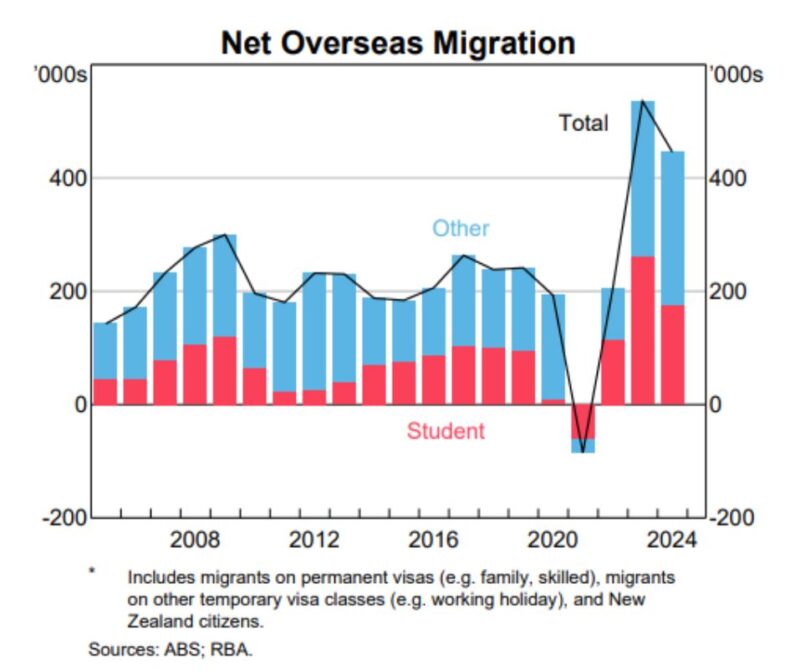

So yes, international students were a major driver of net overseas migration during that period, accounting for roughly half of it.

Source: RBA

But here’s the kicker: the biggest jump in advertised rents occurred before borders even reopened.

In other words, by the time most international students returned, the rental market was already under significant pressure.

The squeeze wasn’t about newcomers arriving, it was about a severe undersupply of rental properties, years of underbuilding, and a fast-recovering local population post-lockdown.

How much did they really add to rental demand?

The RBA did the maths.

Let’s say 50% of new international students rent privately.

An additional 100,000 students would mean about 50,000 new renters.

Based on RBA housing models, this might lift rents by around 0.5%, hardly enough to explain the double-digit rental increases we’ve seen in many markets.

And yes, international students do tend to concentrate around education hubs, think inner-city Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane.

But even there, most of the sharp rental hikes were well underway before they returned in force.

Student spending: a spike, not a surge

Another criticism is that international students drive inflation by spending big when they arrive.

There’s some truth to that, but it’s short-lived.

New visa requirements mean students must prove they have nearly $30,000 in savings to support themselves.

That leads to a burst of spending on arrival: furniture, electronics, setup costs, but then their consumption tapers off.

Excluding tuition fees, the RBA found that international students spend about the same as residents.

So yes, they briefly added to demand pressures as borders reopened, but they were just one of many factors contributing to inflation from 2022 to early 2023.

The real issue? Supply, not students

Here’s where we need to shift the conversation.

Note: Yes, international students rent. Yes, they spend money. But they are not the reason we’re facing a housing crunch.

The real culprits?

-

Years of under investment in housing supply, particularly in the private rental sector.

-

Planning bottlenecks and red tape slowing down new developments.

-

A shrinking pipeline of new dwellings, even as population growth resumed post-COVID.

-

And a rental market already stretched thin by locals returning to cities, falling household sizes, and investor disengagement due to regulatory burdens.

Blaming students is politically convenient, but economically lazy.

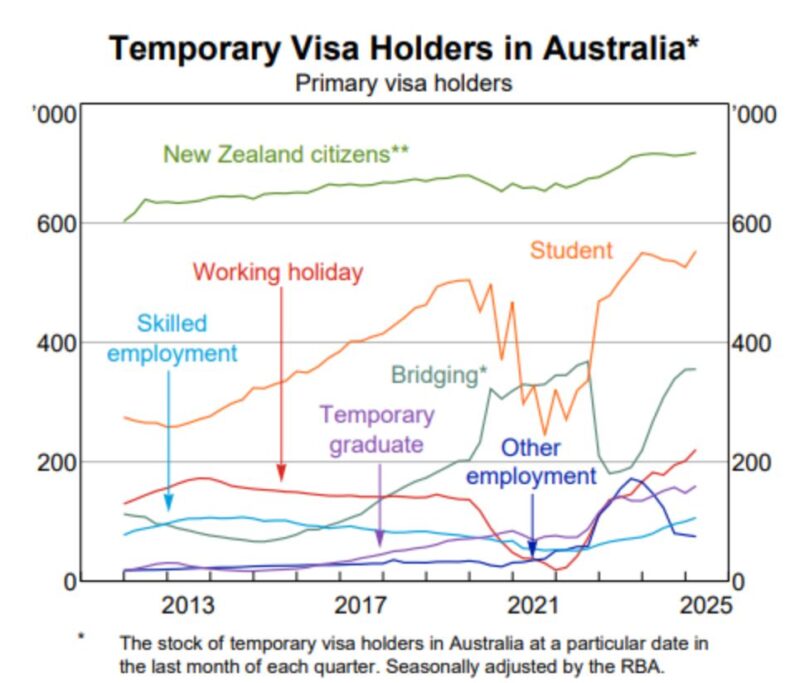

They’re also boosting the economy in other ways

It’s easy to forget that international students are a massive economic asset.

In fact, education is now Australia’s fourth-largest export, worth around $50 billion.

They not only support universities, but also inject demand into retail, hospitality, and housing.

They contribute to the labour force, especially in industries like hospitality and care work.

Source: RBA

And in the long run, some will become skilled migrants, adding to our workforce and tax base while, in the short term, supporting our economy through their consumption.

Yes, recent visa changes are tightening eligibility to reduce migration for its own sake, but that shouldn't obscure their broader value.

What it means for property investors

For those of us involved in the property markets, this RBA report reinforces what we’ve known for a while:

-

The rental crisis is structural, not cyclical. It’s not about sudden demand shocks, it’s about chronic undersupply and a lack of coordinated national housing strategy. Which means it won't go away any time soon!

-

International students are a long-term demand driver, not a short-term problem. Especially in key educational hubs, they support rental yields, retail foot traffic, and purpose-built accommodation projects. They are an important part of Australia's economy, providing export income from their fees and also from their internal consumption.

-

Rental markets remain tight—and if supply doesn’t respond ( and there is no reason to see this happening anytime soon), rents will continue to climb, regardless of student numbers.

The bottom line

The RBA’s research is clear: international students didn’t break the rental market.

And they didn’t cause inflation.

Blaming them distracts us from the real policy and planning failures that have led to today’s housing challenges.

We need to stop looking for scapegoats and start focusing on solutions, like unlocking land, fast-tracking approvals, and encouraging more investment in housing.

Because whether it's students, skilled migrants, or local Aussies, everyone needs somewhere to live.

And that’s something we can’t ignore any longer.