The number of mature age Australians carrying mortgage debt into retirement is soaring.

And on average each mature age Australian with a mortgage debt owes much more relative to their income than 25 years ago.

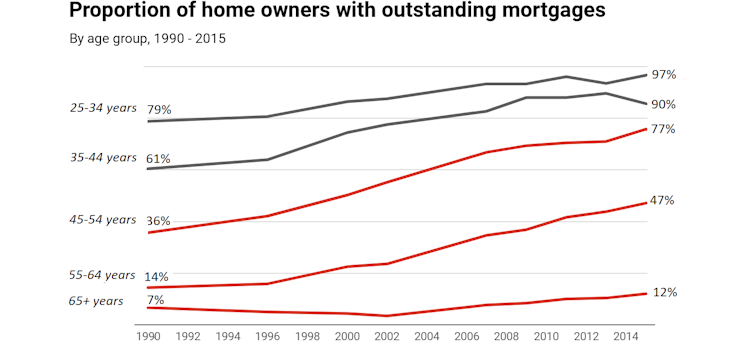

Microdata from the Bureau of Statistics survey of income and housing shows an increase in the proportion of homeowners owing money on mortgages across every home-owning age group between 1990 and 2015.

The sharpest increase is among homeowners approaching retirement.

More mortgaged for longer

For home owners aged 55 to 64 years, the proportion owing money on mortgages has tripled from 14% to 47%.

Among home owners aged 45 to 54 years, it has doubled.

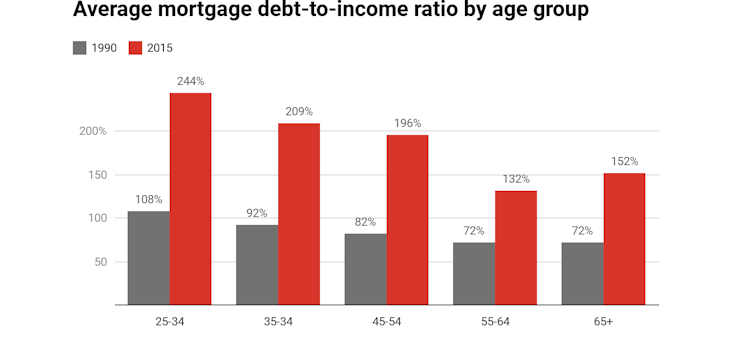

Meanwhile, the average mortgage debt-to-income ratio among those with mortgages has pretty much doubled across every home-owning age group.

In the 45-54 age group the mortgage debt-to-income ratio has blown out from 82% to 169%.

For those aged 55-64 it has blown out from 72% to 132%.

Three reasons why

The soaring rates of mortgage indebtedness among older Australians have been driven by three distinct factors.

First, property prices have surged ahead of incomes.

Since 1970 the national dwelling price to income ratio has doubled.

Sources: Treasury, ABS, Committee for Economic Development of Australia

Despite weaker property prices, the ratio remains historically high.

This means households have to borrow more to buy a home.

It also delays the transition into home ownership, potentially shortening the the remaining working life available to repay the loan.

Second, today’s home owners frequently use flexible mortgage products to draw down on their housing equity as needed for other purposes.

During the first decade of this century, one in five home owners aged 45-64 years increased their mortgage debt even though they did not move house.

Third, older home owners appear to be taking on bigger mortgages or delaying paying them off in the knowledge that they can work longer than their parents did, or draw down their superannuation account balances.

Super could be changing our behaviour

For mortgage holders aged 55-64 years, there is evidence to suggest that larger debts prolong working lives.

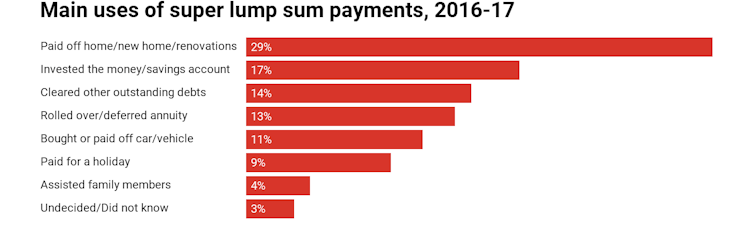

In 2017 around 29% of lump sum superannuation withdrawals were used to pay down mortgages or purchase new homes or pay for home improvements, up from 25% four years earlier.

In the Netherlands, where a mandatory occupational pension scheme along the lines of Australia’s super scheme has been in place for much longer, over one-half of home owners aged 65 and over are still paying off mortgages.

ABS 6238.0 Retirement and Retirement Intentions

The implications are huge

Internationally, studies have found that indebtedness adds to psychological distress.

The impacts on wellbeing are more profound for older debtors, without the ability to recover from financial shocks.

Debt-free home ownership in old age used to be known as the fourth pillar of the retirement incomes system because of its role in reducing poverty in old age.

It allowed the Australian government to set the age pension at relatively low levels.

Growing indebtedness will increase after-housing-cost poverty among older Australians and create pressure to boost the age pension.

Mortgage debt burdens late in working life will also expose home owners to unwelcome risks, as health or employment shocks can ruin plans to pay off their mortgages.

During the first decade of this century, around half a million Australians aged 50 years and over lost their homes.

Taxpayers will be under pressure to help

Those losing home ownership are often forced to rely on rental housing assistance.

Moreover, as older tenants they are unlikely to ever leave housing assistance.

This will put pressure on the government to boost spending on housing assistance, which is likely to further boost demand for housing assistance.

Super and government housing assistance could become the safety nets that allow retirees to escape their mortgages.

It wasn’t the intended purpose of superannuation, and wasn’t the intended purpose of housing assistance.

It is a development that ought to be front and centre of the inquiry into the retirement incomes system announced by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg.

It is a change we’ll have to come to grips with.

Guest author: Rachel Ong ViforJ, Professor of Economics, School of Economics, Finance and Property, Curtin University and Gavin Wood, Emeritus Professor of Housing and Housing Studies, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.