Key takeaways

The Albanese Government’s so-called intergenerational lens is being framed as fairness for young Australians, but Simon Kuestenmacher and I argue it’s more about justifying new taxes on asset owners and retirees.

Simon warned that this framing risks devolving into “the suffering Olympics,” where each generation competes over who had it tougher, rather than tackling the real structural issues like productivity and housing affordability.

While research often claims older Australians receive more “income” through services like healthcare, Simon pointed out that this misrepresents the reality; nobody “benefits” from being sick.

The real divide is in asset ownership, particularly housing. Australia shifted in the 1990s from viewing homes as shelter to treating them as financial assets, which has created wealth inequality between owners and non-owners

Simon explained that rising property values are now baked into Australia’s political and economic system.

State revenues rely on property taxes, banks rely on mortgages, and first-home-buyer schemes that promise “help” actually inflate prices further.

Superannuation remains one of Australia’s best policy achievements, but political arguments over “fairness” have made it a target.

Simon emphasised that while some massive balances might justify review, indexing any cap is essential, otherwise inflation will quietly drag average Australians into rules meant for the wealthy.

If younger Australians believe the system can’t deliver prosperity, because wages stagnate, housing is out of reach, and taxation feels unfair, they’ll disengage from traditional institutions

Australia’s ageing population is becoming the political football no one asked for.

And lately, you can feel a shift in tone coming from Canberra; subtle, quiet, and very intentional.

We’re now hearing the phrase “an intergenerational lens” attached to government policy.

On the surface, it sounds virtuous. Fairness across age groups. Sharing opportunities. Balancing outcomes.

But underneath, many Australians, especially older ones, are wondering: Is this just clever language before the government finds new ways to tax homeowners, retirees, and people who have spent their lives doing the right thing?

The tension is real. And the truth is more complicated than the headlines.

For weekly insights, subscribe to the Demographics Decoded podcast, where we will continue to explore these trends and their implications in greater detail.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player:

The ‘Suffering Olympics’: how generational politics goes wrong

Whenever the debate becomes “young people did it tougher” vs “older Australians did it tougher,” we’ve already lost the plot.

On our latest Demographics Decoded episode, Simon Kuestenmacher put it perfectly when he said policymakers must avoid turning Australia into:

“the suffering Olympics, where everyone tries to prove their generation had it worst.”

That kind of framing divides the nation, blinds us to nuance, and pushes politicians toward cheap symbolism instead of meaningful reform.

And Simon also warned that no generation can ever be compared cleanly:

-

Boomers grew up in a world without global competition for jobs.

-

Gen X entered a labour market shaped by neoliberalism.

-

Millennials hit university just as the digital revolution upended everything.

-

Gen Z entered adulthood during pandemics, supply chain chaos, and housing scarcity.

Different worlds. Different rules. Different pressures.

So pretending we can calculate a single “fairness score” for each generation is simplistic at best, dangerous at worst.

There’s been a surge of research suggesting retirees receive “more than their fair share” of government support once you factor in pensions, concessions, and especially healthcare.

Some commentators even argue that older Australians “consume” $50,000+ per year in services.

But here’s the problem: Counting healthcare spending as “income” is deeply misleading.

You only receive these benefits if you’re sick, injured, or declining.

As Simon put it:

“Nobody enjoys healthcare. That’s not consumption - it’s a cost of staying alive.”

In other words, nobody is “winning” by needing more medical care in their 70s and 80s.

But the political narrative is convenient.

If you want to shift taxation toward older, asset-owning Australians, you first need to paint them as “privileged recipients” of government largesse.

That framing is already being laid.

Housing is the real intergenerational fault line

Let’s be honest, most intergenerational tension isn’t about pensions or healthcare.

It’s about housing, by far the biggest driver of wealth inequality in Australia today.

And Simon nailed the turning point when he explained that sometime around the 1990s, Australia shifted from seeing homes primarily as shelter to seeing them as wealth-building vehicles.

And once housing became an asset class, politicians, banks, and households all became invested in keeping prices rising.

As he put it:

“We created a system where we drive asset prices up and up and up.”

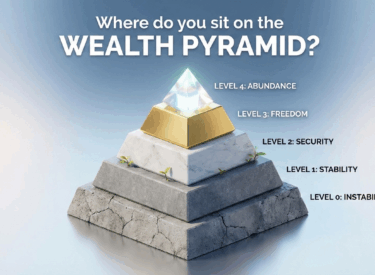

This shift created a massive structural divide:

- Older Australians - Bought when prices were far lower relative to income, even if interest rates were brutal.

- Younger Australians - Face record-high entry costs, ultra-low wage growth relative to asset inflation, and an economy addicted to property as its core wealth engine.

Interest rates are only part of the story. As Simon noted:

-

Those high rates also meant much higher returns on savings, which made deposits accumulate faster.

-

Housing was cheaper relative to income.

-

The economic structure helped younger savers climb the ladder more easily.

It wasn’t easy, but the pathway was clearer.

Today, many feel like they’re running up a down escalator.

The real systemic problem: Governments need high house prices

This is the uncomfortable truth policymakers rarely admit:

Note: Australia’s fiscal, banking, and political systems are structurally dependent on high and rising property values.

Simon gave several sharp examples:

-

First home buyer schemes, once rare, are now constant, and they push prices up.

-

5% deposit guarantees pull more marginal buyers into the market, raising risk, and again, pushing prices up.

-

States rely heavily on property taxes (stamp duty, land tax, etc.).

-

Banks prefer rising home values because mortgages are their most profitable product.

-

Governments quietly become part of the risk when they guarantee low-deposit loans.

As Simon said bluntly:

“Once the government starts guaranteeing home loans, it becomes a stakeholder in keeping house prices high.”

So while politicians talk about affordability, their actions often depend on sustaining the very system that caused the problem.

The greatest future budget crisis? Elderly renters

Here’s the real intergenerational time bomb and according to Simon it’s barely discussed in Canberra.

He highlighted that renters can live perfectly well during their working years. The real danger comes later:

“The moment renters retire, they’re at high risk of poverty. Rent eats too much of the pension.”

If Australia continues growing its renter population, and those renters age, the government faces a massive future welfare obligation.

This is the true intergenerational crisis.

Not boomer homeowners. Not pensioners. Not super concessions. It’s the long-term renter cohort approaching retirement.

If Canberra cared about sustainability, this is where the focus would be, not framing homeowners as a “fairness problem.”

Superannuation: brilliant system, politically easy target

Australia’s superannuation system is world-class, and Simon was emphatic about this:

“Super is one of the smartest things Australia has ever done.”

It forced a generation (starting with the boomers) to fund their own retirement, easing pressure on the Age Pension.

But as balances have grown, especially at the top end, super has become a tempting revenue source for governments seeking new money.

Simon made two critical points:

1. A big balance doesn’t mean the system is broken.

It means it’s doing its job helping Australians retire independently.

2. If the government sets new caps, they must be indexed.

Otherwise inflation slowly drags ordinary Australians into policies meant for the very wealthy, exactly as happened with bracket creep.

Australia has already seen the early signs: “temporary” caps suddenly affecting more people than intended.

And now the government is talking about taxing unrealised gains for balances over $3 million, and that threshold is not indexed.

That’s not fairness, that’s drift taxation.

The true danger: young Australians losing faith in the system

This was perhaps Simon’s biggest warning.

If younger Australians conclude that:

-

they can’t buy a home,

-

wages don’t build wealth,

-

the rules keep changing,

-

and asset owners always win…

…then they will stop believing the system delivers prosperity.

Simon explained that employers are already seeing this shift:

“Give young people a pay rise today, and it doesn’t motivate them the way it used to because money itself doesn’t feel like the path to security anymore."

Homeownership looks too far away. The big milestones seem unattainable.

And when a generation loses faith, they vote for more radical alternatives.

That’s how political systems destabilise.

Simon summarised it in a single sentence:

“If young people don’t feel positive about the system they live in, they’ll vote for options outside the system.”

That’s the real risk, not older Australians having too much wealth.

Where policy should really focus

If Canberra is serious about fairness (not political theatre), here’s where the effort should go.

1. Put productivity at the centre of national strategy.

Real wages only rise permanently through productivity, not redistribution.

Australia needs:

-

faster project approvals

-

more efficient infrastructure investment

-

fewer regulatory handbrakes

-

incentives for innovation

-

workforce upskilling at scale

Redistribution fights over slices of the pie, while productivity grows the pie.

2. Fix energy costs to unlock new industries.

Simon was clear:

“If we want high-tech jobs and advanced industry, we need cheaper, stable energy.”

Energy is now an economic competitiveness issue, not just an environmental policy.

3. Use migration strategically, not bluntly.

It should serve:

-

workforce gaps

-

productivity

-

industry development

-

geographic needs

And not just population growth for GDP optics.

4. Address the ageing renter crisis now.

This is where the system will break if we ignore it.

We need:

-

pathways to ownership across a lifetime

-

retirement security for long-term renters

-

more stable, modern tenancy laws

-

targeted supply in locations ageing Australians actually want to live

5. Tighten super settings but with precision, not politics.

A system designed to ensure retirement adequacy shouldn’t be punished for working well.

Cap excesses if needed — but:

-

make thresholds indexed

-

avoid taxing unrealised gains

-

don’t undermine confidence in long-term retirement planning

The goal should be to strengthen self-funded retirement, not weaken it.

My take: fairness isn’t about taking from one group to give to another

Every generation faces its own version of hard.

Boomers dealt with 18% mortgage rates.

Gen X navigated recession and outsourcing.

Millennials faced exploding house prices.

Gen Z entered a chaotic, unstable labour market.

But the moment we start weaponising these differences, we undermine social cohesion.

The government can talk about “intergenerational fairness” all it likes, but envy is not a policy.

The real question Australia must answer is: Do we want a country where each generation builds on the last…

or one where governments stir resentment to justify new taxes?

As Simon said, and I wholeheartedly agree:

“We don’t need generational warfare. We need generational cooperation.”

Because if we spend the next decade fighting over fairness instead of building opportunity, we won’t just punish younger Australians.

We’ll undermine the very prosperity older Australians worked so hard to create.

If you found this discussion helpful, don't forget to subscribe to our podcast and share it with others who might benefit.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player: