Key takeaways

Despite high GDP per capita and wealth rankings, Australia’s economy is heavily reliant on just four pillars — mining, agriculture, tourism, and international education.

On the Global Economic Complexity Index, we sit at 98th, highlighting our narrow economic base.

Immigration has been a major driver of GDP, filling labour gaps and sustaining consumption.

While essential, it has intensified debates around housing affordability and infrastructure strain — critical factors in whether Australians feel the benefits of growth in their daily lives.

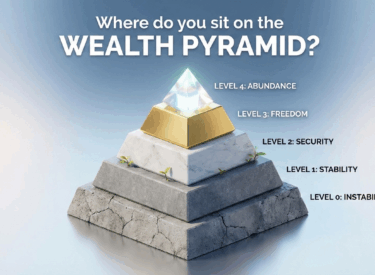

Housing and superannuation make Australians wealthy on paper, but wealth skews towards older generations, leaving younger Australians feeling locked out. This generational divide risks breeding resentment and weakening social cohesion.

For generations, Australians have proudly embraced the phrase “the lucky country.”

It rolls off the tongue easily, evokes sunshine and freedom, and reassures us that somehow, no matter what happens, we’ll land on our feet.

But when Donald Horne coined the phrase in 1964, he wasn’t congratulating us; he was warning us.

He argued Australia’s prosperity was based on luck rather than smart decisions, suggesting that without deeper vision and innovation, our good fortune could one day run out.

Fast forward to today, and the question feels more relevant than ever: are we still the lucky country, or just living off past luck?

For weekly insights subscribe to the Demographics Decoded podcast, where we will continue to explore these trends and their implications in greater detail.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player:

Where we stand in global rankings

On paper, Australia still shines.

Our GDP per capita ranks us alongside the world’s most prosperous nations.

We regularly sit above Canada and the Netherlands, countries that, like us, combine rich resources with relatively small populations.

In fact, by many economic yardsticks, we are one of the wealthiest nations on Earth.

But as demographer Simon Kuestenmacher points out in our latest Demographics Decoded episode, those statistics hide some uncomfortable truths.

“If you look at the Global Economic Complexity Index, Australia ranks 98th, just behind Uganda,” Simon says.

“We are not an overly complex economy. We are lucky. Our prosperity comes from a handful of sectors: mining, agriculture, tourism, and international education. Those four things don’t make for a complex economy, but they do generate plenty of GDP.”

So while we appear wealthy, our economic base is surprisingly narrow. And that narrowness leaves us exposed.

The power and the risk of mining

The mining sector is the powerhouse of the Australian economy.

Mining generates around $1.1 million of GDP per worker per year, over three times more than finance or property.

That staggering productivity explains why, as Simon puts it, “mining is very, very sexy” in economic terms.

Our resource wealth has been supercharged by China’s rapid growth over the past 30 years.

Iron ore, coal, and gas exports built a windfall that funded higher wages, boosted government revenues, and supported decades without a recession.

But as China’s demand cools, questions arise about how long we can rely on this golden ticket.

Simon remains optimistic:

“Yes, China’s urbanisation is slowing, but ‘China 2.0’ exists, countries like India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines. They’re growing quickly from a lower base, and eventually they’ll need our resources too. Structurally speaking, I’m convinced there will always be demand for the stuff we dig out of the ground.”

Still, this reliance means our fortunes swing with global commodity prices.

Few nations willingly sacrifice economic growth for environmental or moral reasons, but Australia faces mounting pressure to balance the wealth of mining against climate concerns.

Migration and demographics: our other growth engine

Beyond resources, migration has been the other great driver of Australia’s prosperity.

New arrivals boost GDP by filling labour shortages, paying taxes, and often becoming international students who add to our education exports.

As Simon explains:

“Every worker, every international student adds to the GDP base. In fact, some people say all of our recent GDP growth was driven by migration. But if you average out migration numbers from the pandemic to today, we’re simply catching up to where we would have been. There’s been no real surge.”

With unemployment low, immigration has filled vital gaps and propped up consumption.

But it has also sparked political debate, particularly around housing affordability and infrastructure strain; two areas that will determine whether Australians feel our “luck” in their day-to-day lives.

Where did the wealth go?

Unlike nations that built sovereign wealth funds, much of Australia’s wealth has flowed into property.

Our housing market is now worth $11.7 trillion, making it our biggest store of national wealth.

Combined with compulsory superannuation, it means Australians are wealthy on paper by world standards.

But this wealth isn’t evenly shared.

Older Australians, especially baby boomers, hold much of it in housing equity. Millennials and Gen Z, by contrast, often feel shut out.

“Millennials feel they won’t end up as rich as their parents, unless they inherit it,” Simon observes. “That sense that the system isn’t working for them creates resentment. The risk is that people fall into a victim mindset, blaming others: boomers, migrants, governments, rather than recognising their own agency.”

That mindset shift is dangerous.

It erodes confidence and social cohesion, even in one of the most prosperous societies in history.

Lessons from abroad

Comparisons with other nations help highlight Australia’s strengths and weaknesses.

- Brazil: A resource-rich country with a hollowed-out middle class and stark inequality. “Australia isn’t Brazil,” Simon stresses, “but we are edging towards a society where the middle class shrinks while the extremes grow. That weakens social cohesion.”

- Germany: A high-wage economy with world-class apprenticeship systems and strong investment in education. Germany shows that high wages needn’t be a barrier to manufacturing or innovation. It’s a reminder that Australia could build resilience by investing more in skills, training, and diversified industries.

These comparisons underline a sobering truth: Australia has been slow to reinvest its luck into long-term, diversified prosperity.

The future: lucky or smart?

Looking ahead 20 or 30 years, Simon is confident our four economic pillars: mining, agriculture, tourism, and international education, will still generate wealth.

But whether Australia becomes smarter with its luck is another story.

“To diversify, we need to massively lower energy costs,” he says. “If we want to move from exporting raw iron ore to exporting high-value steel, energy prices would need to fall to a third of what they are today. Without that, I expect more of the same.”

That means Australia’s prosperity will likely continue, but with the same vulnerabilities: housing affordability, inequality, reliance on resources, and exposure to global shocks.

Final thoughts

So, is Australia still the lucky country?

By almost any global measure, yes.

We are rich, safe, stable, and envied by many. But luck alone won’t secure the future.

The bigger question isn’t whether we’re lucky, it’s whether we’ll be smart enough to invest that luck wisely.

Will we continue to funnel wealth into housing, or will we build sovereign wealth funds, lower energy costs, and invest in skills that strengthen the middle class?

Our challenge isn’t to be lucky, it’s to stay lucky, while ensuring that prosperity is broadly shared and sustainable.

That’s what will determine whether future generations look back and still call Australia the lucky country.

If you found this discussion helpful, don't forget to subscribe to our podcast and share it with others who might benefit.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player: