Key takeaways

In the past, each generation improved economically: more education, better jobs, homeownership, and longer lives.

That upward trajectory is now in question, especially for Millennials and Gen Z.

Young Australians are increasingly skeptical that they’ll be wealthier or more secure than their parents.

Recognising generational shifts allows savvy investors to anticipate changes in housing demand, family formation, and asset preferences.

Don’t count out young Australians—they’ll still build wealth, but on different timelines and terms.

As always in property, the earlier you understand the macro trends, the better positioned you are to benefit from them.

Will today’s younger generations end up wealthier, happier, and more secure than their parents?

That used to be a no-brainer.

For much of Australia's modern history, each generation climbed the economic ladder higher than the one before it. More education, better jobs, bigger homes, longer lives.

But that narrative is now being questioned, especially by the very people meant to live it.

So, are young Australians still on track to be better off? Or has the promise of generational progress quietly slipped away?

Let’s take a closer look at what the evidence really says—and what it means for us as property investors and wealth builders.

Let’s start with some context

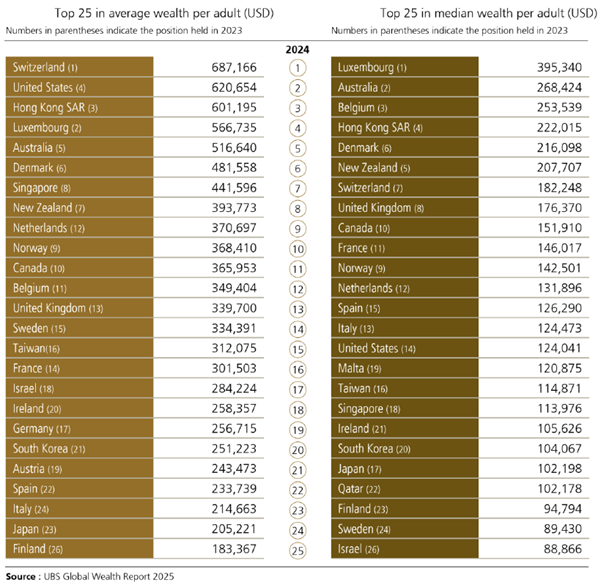

According to the 2025 UBS World Wealth Report, our wealth increased by 11% in 2024, and Australia ranks second globally in terms of median wealth per adult.

However, most of Australia’s wealth is concentrated in the hands of Baby Boomers, and there are a few clear reasons why.

Firstly, Boomers have simply had time on their side.

Many entered the workforce during an era of strong wage growth, affordable property prices, and generous superannuation reforms.

They were able to buy homes in the 1970s, 80s and even early 90s—when median house prices were just a few times the average income, not 8 to 10 times like they are today.

As the decades rolled on, rising property values and favourable tax policies supercharged the wealth of owner-occupiers and investors alike.

Secondly, Baby Boomers benefited from stability.

They lived through a period of economic expansion, lower education costs, and more secure full-time employment.

Many now have built up sizable equity in their homes, often being mortgage free.

Add to that the rise in share market participation through superannuation, and for some, inheritances from their own parents, and it’s easy to see why this generation holds a disproportionate slice of the nation’s wealth.

Today, Boomers control more than half of Australia’s private wealth, despite representing only a quarter of the population.

This isn’t unfair - it reflects a lifetime of accumulation, but it raises important questions about intergenerational equity and how that wealth will be transferred in the decades ahead.

So back to the original question – will young Australians be better off than their parents?

E61 Institute looked at this and came up with some interesting findings…

A generation that’s more educated and more indebted

There’s no doubt that young Australians are the most highly educated generation in our nation’s history.

They’re more than twice as likely to hold a university degree as their parents were at the same age, and they’re far less likely to drop out of school early.

That’s a win.

But education hasn’t come cheap.

More than 30% of Australians under 35 now carry a student debt, up from 20% a decade ago, and the average HELP debt has ballooned to over $26,000.

Many are still paying off that debt well into their mid-30s, right when they’re trying to save a deposit or start a family.

It’s not just the size of the debt—it’s the timing.

And it’s holding them back.

Earning more… but taking home less?

Young Aussies are earning similar real wages to those who came before them.

In fact, early-career earnings are broadly comparable to those of Gen X.

But after the Global Financial Crisis, income growth for under-40s has fallen dramatically behind that of older Australians.

Add to that a shift toward insecure, lower-paid work and reduced job mobility, and you get a generation struggling to build financial momentum.

And while older Australians enjoy tax-free gains on their homes and capital gains discounts on their investments, younger workers carry the growing burden of income tax, courtesy of bracket creep.

And while some Gen Zs will benefit from the largest wave of inheritances in Australian history, as I mentioned above, these windfalls often come too late, usually in their 50s.

That doesn’t help much when you're 30, renting, and trying to raise kids.

The homeownership dream is fading

Nowhere is the generational gap more visible than in housing.

Homeownership rates among 25–34-year-olds have plummeted.

Even many professional millennials now view homeownership as a pipe dream, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne.

As a result, more young adults are staying in their family home longer - nearly 60% of 18- to 24-year-olds still live with their parents, and fewer are forming relationships or having children before the age of 30.

This isn’t just a lifestyle choice.

It’s a response to affordability pressures and economic precarity.

The traditional life path - job, partner, home, kids - is being delayed, or in some cases, rewritten entirely.

Diverging experiences: gender and geography matter

There’s no single “youth” experience in Australia anymore.

For example , young women are earning more than their male peers in early careers, driven by higher educational attainment and growth in female-dominated sectors like healthcare.

But they’re also experiencing declining mental health and higher levels of loneliness and hospitalisation.

Meanwhile, some young men, particularly in regional locations, are falling behind, facing higher unemployment, lower education rates, and rising rates of disengagement.

And the divide doesn’t stop there.

In some remote areas, up to 30% of 20–24-year-olds are not in employment, education or training. That’s a massive pool of untapped potential.

The mental health and technology double-whammy

Young Australians are also the first generation to grow up fully online.

They’ve gained access to more information, more choice, more opportunity.

But they’ve also inherited a suite of new problems: social media addiction, increased anxiety, and declining mental well-being.

Mental health scores for young women have fallen significantly over the last decade.

And young men are showing signs of risky behaviour in other areas - gambling, for instance, has doubled among young men since 2015, and surprisingly, it’s not just online betting - it’s pokies.

In other words, technology has reshaped how young Australians interact, form relationships, and take risks, but not always for the better.

The inheritance economy but only for some

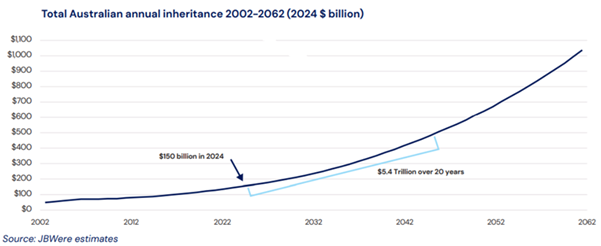

Australia is on the brink of the biggest wealth transfer in its history.

Inheritances are expected to quadruple by 2050.

However, these gains will be unevenly distributed; many will receive little or nothing, and they often arrive too late to support early financial milestones.

JBWere estimates that some $5.4 trillion of this wealth will be transferred to younger generations over the next two decades.

However, this won’t be passed on to Gen Z or millennials anytime soon – it will be passed on to their parents.

And while some young Australians will eventually catch up through bequests and asset appreciation, others won’t.

And that could cement a new kind of inequality, not just between generations, but within them.

So… are they better off?

That depends.

If we’re measuring in raw education levels, life expectancy, or access to digital tools - yes, young Australians have got an edge.

But if we’re talking about financial independence, homeownership, relationship stability, or mental wellbeing, many young Australians are facing a much rougher road.

In reality, the story isn’t one of decline, but delay.

Life milestones are being pushed back, reshaped, and in some cases, reimagined.

According to the E61Institute report , the challenge for policymakers is understanding these shifts and preparing for what comes next.

Final thoughts for property investors and business owners

Why does this matter to you as a property investor or business owner?

Because understanding generational change gives you insight into tomorrow’s housing market, workforce, and economy.

Young Australians may be buying later, renting longer, and starting families in their 30s- but that doesn’t mean they won’t build wealth.

They’ll just do it differently. Some will inherit, some will invest, others will co-buy or rentvest.

But they’ll still need homes. They’ll still chase financial independence. And they’ll still be looking for opportunities in a rapidly changing world.

Your job is to see the trends early, adapt, and invest accordingly.