Key takeaways

After World War II, homeownership became central to the Australian identity, driven by government policy, migration, and the availability of affordable land.

Homeownership peaked at 73% in 1966, underpinned by rising dual incomes, easier access to finance, and strong cultural aspirations.

Today’s rate sits at ~66% – still high globally, but with a deepening generational divide.

For generations, the Great Australian Dream of homeownership was almost a given.

It wasn’t just a goal, it was seen as a rite of passage.

But today that dream is becoming harder to achieve.

While some point fingers at migrants or property investors, the reality is far more complex.

So in this week’s Demographics Decoded Podcast Simon Kuestenmacher and I take a deeper look at how we got here, what’s really going on beneath the surface, and what this means for our future.

For weekly insights and strategic advice, subscribe to the Demographics Decoded podcast, where we will continue to explore these trends and their implications in greater detail.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player:

The journey from post-war boom to today

If we go back to the 1930s, only about 60% of Australians owned their home.

Many lived in rental properties, often controlled by private landlords, at a time when rental protections were minimal.

As Simon Kuestenmacher noted in our latest Demographics Decoded episode, this reflected a society still reeling from the Great Depression, where low-income workers lived hand to mouth, with homeownership out of reach for most.

Source: Avid Commentator Substack

Then things changed dramatically after World War II.

The Menzies government stepped in with bold housing initiatives aimed at returned servicemen.

Land was made affordable, and building a home became a pathway to both economic prosperity and social stability.

The post-war migration boom added fuel to the fire.

Migrants from Greece, Italy, and elsewhere not only helped build the homes but also embraced the dream themselves, a dream they passed on to their children and grandchildren.

By 1966, homeownership peaked at 73% of dwellings, a figure underpinned by easier access to finance, the rise of building societies, and the growing inclusion of dual incomes in lending assessments.

Back then, borrowing was harder, but with the right policy mix, people could afford to buy.

Source: CheckRate

The decline in homeownership rates

Today, homeownership has slipped to around 66%.

Now, that’s still high by international standards, but it masks some uncomfortable truths.

One is the generational divide.

As Simon pointed out, “The average 30-year-old today is far less likely to own a home than their parents or grandparents were at the same age.”

Why?

Because we’ve changed the timeline for adulthood.

In the 1950s, most young people entered the workforce straight from school.

They began saving, bought a home earlier, and paid it off over decades.

Today, we encourage higher education, meaning many young adults only begin earning meaningful money in their mid-20s, at a time when house prices have soared beyond their parents’ wildest dreams.

At the same time, we haven’t built new major cities since the Gold Coast emerged in the 1950s.

Despite our vast continent, we’ve created artificial land scarcity by concentrating growth in just a few urban centers.

Combine that with our failure to deliver large-scale social housing since the 1960s and ’70s, and it’s no wonder we’re seeing rising prices and falling ownership rates.

Why we can’t blame migrants or investors

It’s tempting to look for scapegoats especially migrants.

Well, we had a perfect natural experiment during COVID when net migration turned negative, yet house prices surged.

As Simon aptly said, that alone should tell us the story is about more than just population growth.

And what about investors?

Yes, investors, particularly the so-called mum-and-dad landlords, have benefited from tax concessions and the security that property provides.

However, even if you were to remove the tax breaks, Simon reminds us that property would still attract investment because it’s “a safe and scarce resource” in Australia.

The real problem is that we’ve built a system that prompts investors to buy, while making it harder for first home buyers to compete.

Interestingly, the government’s promotion of built-to-rent projects aims to shift rental stock into institutional hands.

But as we’ve seen, these projects, while adding supply, aren’t delivering affordable rentals.

They’re well-appointed, well-located, but they’re not cheap.

As Simon put it, “Built-to-rent in its current form is still profit-driven, not designed for affordability.”

The growing intergenerational wealth divide

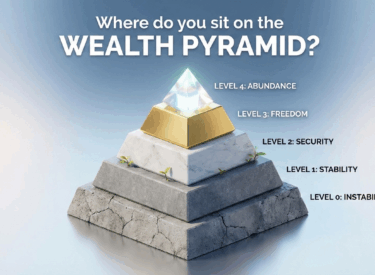

Here’s where the real long-term risk lies.

The divide between those who own property and those who don’t is widening, and that gap is being handed down through the generations.

The Bank of Mum and Dad has become one of the largest lenders in the country, helping those lucky enough to have wealthy parents get on the property ladder.

Simon highlighted a powerful truth: A $100,000 parental gift doesn’t just cut a deposit shortfall - it can save a family hundreds of thousands in interest over the life of a mortgage.

And if you don’t have that support you’re not just behind, you’re falling further back through no fault of your own.

This challenges the notion that we live in a purely merit-based society where hard work alone gets you ahead.

Are we drifting towards a European-style rental market?

The short answer: yes, to a degree.

Renting will become more common, and as Simon points out, this will bring policy changes.

We can expect to see stronger protections for renters, increased rights, additional responsibilities for landlords, and possibly a shift in how property management is conducted.

But here’s the difference: Europe’s rental models are often supported by large-scale institutional landlords and significant public housing programs.

Australia isn’t there, and we’re not on track to get there either, at least not anytime soon.

Policy responses: sugar hits, not solutions

Many of the measures we see today, whether it’s first home buyer grants, government-backed loans with 5% deposits, or super-for-housing schemes, do little to address the root issues.

They assist some people into the market, yes, but they also inflate demand without dealing with supply or structural affordability.

As Simon said, “These are policies designed to keep the current system running.”

Real reform would mean rethinking land use, infrastructure, taxation, and social housing policy.

But that would require political courage, and as history has shown, when Bill Shorten proposed modest changes to negative gearing and capital gains tax, the political risks are high.

Most voters own property or aspire to, so there’s little appetite for change that might depress prices.

Where do we go from here?

The forces driving the decline in homeownership are multifaceted, encompassing demographic, economic, social, and political factors.

There is no single culprit and no silver bullet solution.

But one thing is certain: unless we find ways to make housing more accessible, we risk deepening inequality and establishing a permanent class of renters with no stake in the property market.

That’s not good for individuals, and it’s not good for our society.

We need a conversation that’s honest about the challenges and courageous about the solutions.

Because the Great Australian Dream shouldn’t just be for those with wealthy parents, it should be within reach for anyone willing to work for it.

If you found this discussion helpful, don't forget to subscribe to our podcast and share it with others who might benefit.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player: