While called a transportation plan, it was heavily skewed towards roads, we need the type of city-shaping thinking that underpinned the plan, but today's plans must match 21st-century priorities, writes ...

Liam Davies, RMIT University and Ian Woodcock, Swinburne University of Technology

This is the first article in a series to mark the 50th anniversary of the landmark Melbourne Transportation Plan.

The 1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan was perhaps the most influential planning policy in the city’s history.

Every freeway and major arterial road built since then, as well as many current freeway and tollway projects and proposals, stem from this plan.

Given current debates about freeway construction (East West Link, West Gate Tunnel, North East Link, Roe 8 and WestConnex) and increasing commute times across Australia, it is timely to reflect on the 1969 plan and lessons to be drawn from this experience.

The post-war boom and the car

Melbourne boomed after the second world war.

The population grew from 1.2 million in 1947 to 2.1 million in 1966.

At the same time, technological changes transformed our way of life.

New manufacturing opportunities provided jobs to support families and consumer goods to fill their lives with.

The Australian dream of a family home on a quarter-acre block was reinforced in this era.

Cars shaped the post-war suburbs.

Estates typified by free-standing dwellings with garages had become the norm by the 1960s.

The opening in 1960 of Chadstone, Melbourne’s first modern shopping mall based on the US model, set the pattern for car-based planning.

The 1954 Metropolitan Planning Scheme embraced these trends.

It proposed low-density car-based suburban development and a freeway system to serve it.

These policies were adopted across the English-speaking world, with the United States its primary advocate.

Notoriously, from the 1920s to the 1950s motor car interests had bought up tramway systems that had shaped many US cities, replacing them with buses that were far less popular.

The culture of the car was created; it wasn’t inevitable.

This pattern was followed in the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia, where trams were ripped out of every capital city except Melbourne.

The 1969 plan

This environment was the context for the 1969 plan, which US consultants supervised.

Faith in the desirability of a car-based future obscured the flaws in the transport modelling assumptions.

The plan forecast a rise in car usage and laid out an extensive road network to support this.

It did not discuss effects on urban form, merely characterising itself as supporting the 1954 Metropolitan Planning Scheme and existing development trends.

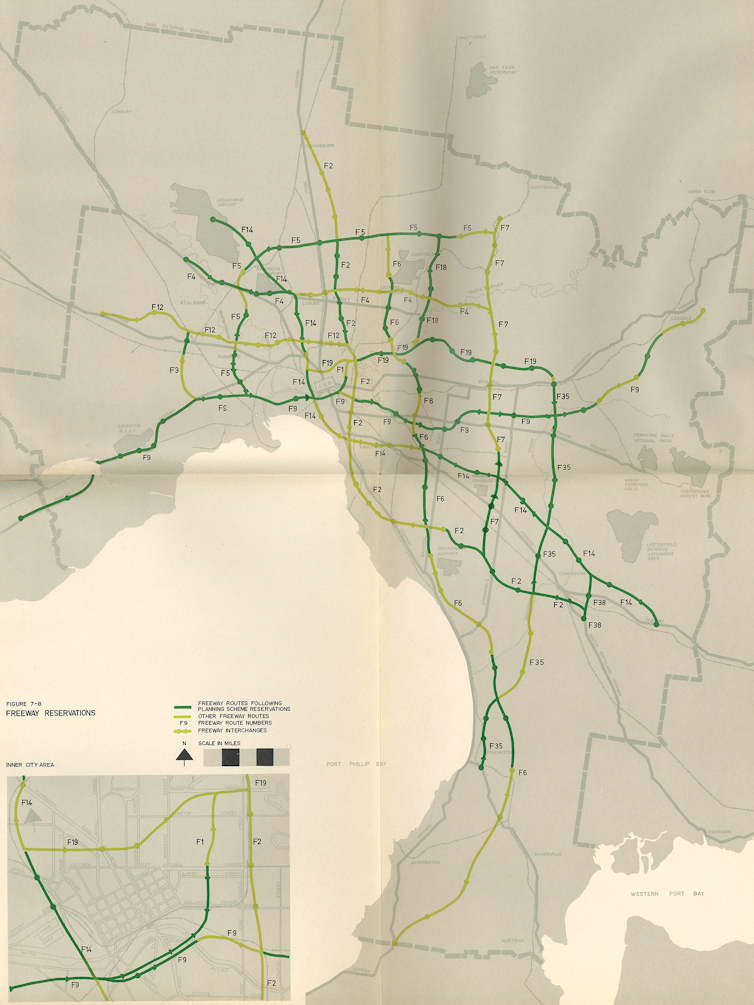

The plan proposed 307 miles (494 kilometres) of freeways.

This accounted for 64% of the proposed spending.

The network was to provide for the predicted 6 million daily car trips by the plan’s scheduled completion in 1985.

1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan

A 323-mile (520km) highway and arterial road network – both new and widened roads – was to support the freeway network.

Some 80 level-crossing removals would promote free-flowing traffic.

Combined, these road proposals were costed at A$2.2 billion (in 1969 dollars) – 85% of the proposed budget.

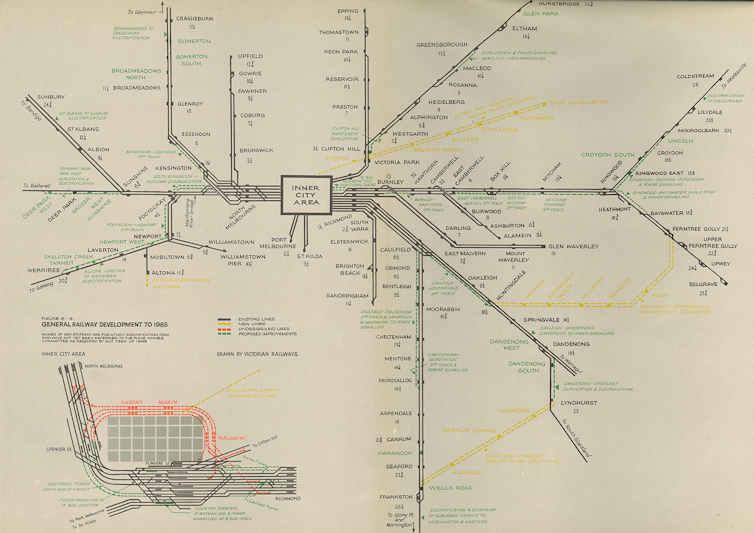

In contrast to the rest of Australia, the plan proposed retaining and modernising Melbourne’s tram system.

There were to be 910 new trams (the system today has about 475).

The plan also included rail improvements, notably the City Loop, electrification to outer areas, rail duplications or triplications, new radial lines to Doncaster and Monash, and suburban loop lines between Huntingdale and Ferntree Gully and between Dandenong and Frankston.

Only 13.5% of the plan’s spending was to be on rail.

1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan

The community responds

The plan triggered a backlash against freeways being built through urban neighbourhoods.

Residents mobilised against demolitions and what they saw as the destruction of their neighbourhoods.

Communities were already opposing the Victorian Housing Commission’s campaign of “slum reclamation” and high-rise tower construction.

The Eastern Freeway (F19) construction, begun in 1970, was fiercely opposed.

Protests increased through the 1970s.

Barricade! – the resident fight against the F19

Public opposition was partly responsible for the plan’s scope being reduced in 1973.

The changed social context of the 1970s demanded a more responsive government.

As attitudes and expectations change, so too must the plans for cities.

How might things have been different?

The 1969 plan laid out a freeway network as a blueprint for subsequent governments to follow.

Much of this network has been built, but very few of the public transport projects were implemented.

The City Loop rail tunnels opened in stages from 1981 to 1985, but only the smallest of the rail extensions has been built.

Some lines have closed since 1969.

This has marginalised the rail system’s usefulness to most people except those travelling to and from the central city.

The effects on Melbourne have been profound and far more biased towards cars than even the plan intended, yet things could have been otherwise.

Washington DC and Vancouver both proposed extensive freeway networks in the 1960s.

In these cities, governments responded to community opposition by shifting the focus towards public transport, cycling and walking.

Rising transport emissions are the largest single contributor to global heating.

Melbourne is at a tipping point, needing to embrace transport options that lower emissions and support sustainable urban development.

Victoria’s 2010 Transport Integration Act has a progressive vision that includes minimising long commutes and reducing reliance on cars.

Arguably, a continued emphasis on road development will frustrate these objectives.

Current rail projects are largely playing catch up.

If all of the lines proposed in the 1969 plan, along with its level-crossing removals, had been completed as planned by 1985, Melbourne would be quite different today, and for much less than the cost of all of the roads built or planned in the foreseeable future.

We should plan now for the future city we want to live in. Melbourne doesn’t need to tear down its suburbs and rebuild them at high densities before better public transport can be justified.

The city needs to focus on better alternatives to cars to give its citizens choices as many other cities have done.

This is an immense challenge, but we should look back on 1969 to see the long-term impacts such a plan can have.

Despite its name and breadth of content, it was a road plan rather than a comprehensive transport plan.

Yet we need the type of long-term city-shaping thinking that underpinned that plan, but directed in ways that fit a genuinely sustainable, smart and fair 2019 vision for 2069 that we can all support.

A public event to mark the 50th anniversary of the Melbourne Transportation Plan will be held on December 12 2019, hosted by RMIT University, supported by Swinburne University, Monash University and the University of Melbourne – details here.

Liam Davies, PhD Candidate, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University and Ian Woodcock, Senior Lecturer, Director of Urban Design, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.