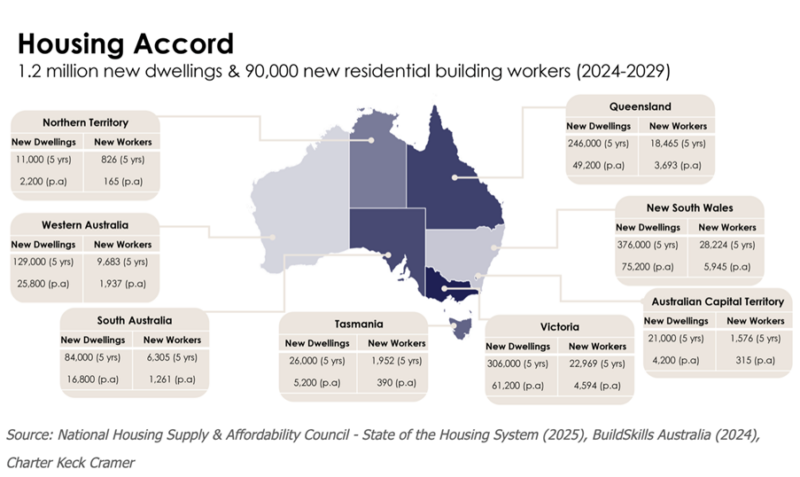

The government wants to build 1.2 million new homes by 2029.

That’s ambitious.

It sounds impressive.

And frankly, it’s what we need - at least 240,000 new dwellings per year to bring our housing market back into balance.

Valuers Charter Keck Cramer have broken down these figures to a state and territory level to understand the magnitude of this task.

So let’s be real: we’re not going to hit that target. Not even close.

And that means our rental crisis is here to stay, for at least another decade.

Why the numbers don’t stack up

In 2017, during one of the strongest years for housing construction, we managed to deliver around 220,000 new dwellings.

That was a peak year, supercharged by active investors (both local and foreign), lower building costs, favourable tax settings, and booming greenfield and apartment markets.

Fast forward to today, and the landscape is very different.

We’re facing:

- A construction cost crisis that’s made many projects financially unviable,

- Planning bottlenecks that delay or prevent much-needed developments, and

- A serious shortage of skilled labour - BuildSkills Australia says we need 90,000 more residential construction workers just to attempt to meet these targets.

And all this is playing out in a much more fragmented, complex market where policy settings change every election cycle.

Reforms? Yes. But That’s a Long Game

To fix this, we need more than just lofty targets and wishful thinking.

We need deep, structural reform:

- Tax reform, to encourage more private investment and build-to-rent initiatives.

- Planning reform, so that approvals don’t get bogged down in red tape.

- Labour reform, to attract, train, and retain the construction workforce.

- Immigration reform, to align population growth with infrastructure capacity.

Some state governments are moving in the right direction on planning.

That’s good.

But it’s just one part of a much bigger puzzle.

And here’s the kicker: even if we get all the reforms right, and get them done now, it’ll still take years to see the results.

Planning changes generally take 7–10 years to truly filter through the market.

That’s one to two full market cycles.

The harsh reality

The 5-year window the government is banking on to “rebalance” the market is simply not realistic.

It’s aspirational.

But unless we hit record-breaking construction levels every single year, at a time when feasibility has never been more strained, we won’t meet demand.

This means the cost of new accommodation will keep rising for home buyers and renters will continue to face rising costs as vacancy rates will remain painfully low.

The bottom line

Even with the best intentions and some positive steps, we are structurally unprepared to solve the housing crisis in five years.

This isn’t a short-term problem. It’s a long-term, multi-decade challenge.

So let’s stop pretending we can fix it quickly.

The government must stay the course with bold, evidence-based decisions, even the unpopular ones.

If they do, we might not see results tomorrow, but we’ll be laying the foundation for a more balanced housing market for future generations.

Until then, buckle up—our rental crisis is going to be with us for a long while yet.