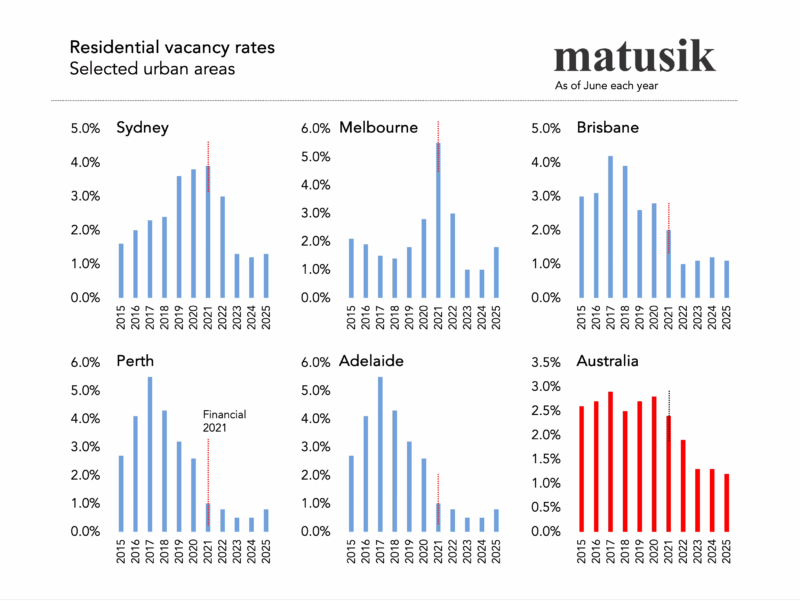

National rental vacancy rates have fallen off a cliff since Covid.

They dropped from the “normal” 2% to 3% range in the late 2010s to barely 1% since 2021. That’s as tight as I’ve ever seen in the data - and as the charts show, there’s been no bounce back across most major urban areas across Australia.

Why? And what could be done to restore some balance? Let’s dig in.

Ten reasons vacancies fell - and never recovered

1. Borders slammed shut

When international students and tourists vanished in 2020, many CBD apartments sat empty. But many landlords quickly switched to domestic tenants, shrinking the pool of available stock elsewhere.

2. Household splitting (temporarily)

Lockdowns prompted divorces, young adults moving out, and work-from-home setups where people wanted their own place. That meant more dwellings were needed per capita - at least for a while.

3. Lifestyle migration

Covid triggered the “Byron effect” - city renters fled to regional areas chasing space and lifestyle. Rental markets in places like the Sunshine Coast and Ballarat went from slack to bone-dry.

4. Short-stay conversions didn’t last

Thousands of Airbnb’s flipped to long-term rental during lockdowns. Once travel resumed, much of that stock went straight back to holiday letting.

5. Stimulus + cheap money fuelled owner-occupier demand

Renters became buyers thanks to 2% mortgage rates and HomeBuilder. But because investors were selling to those buyers, it reduced the rental pool.

6. Investors retreated

Even before Covid, tighter lending rules, land tax hikes, and low yields discouraged investors. Lockdowns amplified that. Many preferred to sit on capital gains rather than deal with tenants.

7. Population snap-back

Borders reopened, and migration roared back. India, China, and the UK led the charge. More people piled into a rental market already running on fumes.

8. Construction fell in a heap

Labour shortages, material cost blowouts, and builder collapses gutted the pipeline. We didn’t approve enough in 2020–22, and even those approvals have been slow to materialise. That means completions are at multi-year lows, compounding the vacancy crunch.

9. Students and CBD renters returned

By 2022–23, the inner-city vacancy blip ended. International students and young renters rushed back, soaking up the slack.

10. Australia’s structural undersupply

Covid simply exposed what was already true: we don’t build enough, approvals often take too long, and planning is too restrictive. The “buffer” was wafer-thin, and it’s gone.

Household size - the missing piece

Some commentators still trot out the “Covid shrank households” line as the ongoing reason for tight vacancies.

I don’t buy it.

Yes, for a short period in 2020–21, household size did fall. But today the evidence points the other way:

- Overseas migration is driving more group households, especially among students and new arrivals.

- Affordability pressures are forcing more people to share - tenants are doubling (even trebling) up.

- Boomerang kids are back living with parents to save for deposits.

- Older Australians are shunning aged care, living with family instead.

In other words, average household size is increasing again.

And that should, in theory, reduce demand per capita.

The fact vacancies are still running at 1% despite bigger households tells us supply is the real culprit.

The great Australian “shadow stock”

Here’s another overlooked factor. My work shows that about 580,000 investment dwellings aren’t rented out at all. That’s around 41% of the investor pool.

These homes fall into a few buckets:

- Holiday homes barely used.

- Future retirement pads left idle.

- Speculative land banks waiting for capital gain.

- Renovation or knockdown plans in limbo.

Covid made it worse. Some investors mothballed properties to avoid tenant rent freezes or eviction bans. Others kept them as family escape hatches.

Was this the reason vacancies collapsed?

No. But if even a fraction of that shadow stock was released, the national vacancy rate would double overnight.

So, how do we get back to 3%?

Here are five things Australia could do over the next 3 to 5 years.

None are silver bullets, but together they’d make a dent.

1. Unlock the locked-up homes

Tax or incentivise owners to rent out vacant dwellings. Extend vacancy levies (like Vancouver’s) beyond token CBD zones. (More on this in coming weeks). Offer tax breaks for renting granny flats or spare rooms. Even freeing up 20% of that shadow stock would change the game.

2. Supercharge build-to-rent and land lease

Cut GST, fast-track approvals, and push mid-sized projects (50 to 200 units). Mandate some affordable units. Expand land lease beyond the over 55 market. Back modular or manufactured housing that can scale quicker.

3. Let the missing middle rip

Relax zoning and the rules to allow terraces, duplexes, and secondary dwellings in middle suburbs. Reduce minimum allotment sizes. Pre-approve standardised designs. Enforce council DA deadlines. Under the right circumstances small-lot infill can deliver faster than endless greenfield estates or fantasy large apartment builds.

4. Reset investor incentives

Tilt negative gearing and depreciation rules to favour actual rentals, not speculation. Penalise short-term letting where housing is tight. Reward investors who commit to long leases.

5. Stabilise construction

Underwrite builder finance or provide infrastructure targeted incentives so projects don’t stall. (Again, more on this in a few weeks). Bulk-buy materials nationally to ease supply shocks. Encourage prefab and modular solutions to build cheaper, faster.

The bottom line

Vacancy rates collapsed during Covid for a cocktail of reasons - border closures, lifestyle shifts, investor retreat, Airbnb’s flipping, and above all, weak supply.

The short-term household splitting narrative is a red herring.

The bigger story today is the combination of rising household size, surging migration, stalled construction, and hundreds of thousands of dwellings sitting idle in the shadows.

Australia needs to stop pretending this is just a “cycle.” Getting back to 3% vacancy will require a range of actions.

The good news? None of these fixes are rocket science.

The bad news? We’ve been talking about them for decades, and only a handful of councils or states have done anything serious.

Until we get real, tenants will keep competing like it’s a game of musical chairs. And the vacancy rate charts will keep hugging the floor.