The Reserve Bank's best case scenario is that its forecasts are wrong, writes ...

Peter Martin., Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe has said two things about unemployment in the past few weeks.

Together, they lead to an inescapable conclusion.

The first was in a speech in May, expanded on in a speech in June.

At both times the published unemployment rate was 5.2%.

Lowe said in May that while the Reserve Bank had long thought an unemployment rate of 5% was the best that could be achieved without generating worrying inflation, that view has now changed:

From today’s perspective, I think we can do better than this. My judgement of the accumulating evidence is that the Australian economy can support an unemployment rate of below 5% without raising inflation concerns.

It was good news. And then it got better.

In June he put a number on how low the unemployment rate could go before inflation became a concern:

While it is not possible to pin the number down exactly, the evidence is consistent with an estimate below 5%, perhaps around 4.5%. Given that the current unemployment rate is 5.2%, this suggests that there is still spare capacity in our labour market.

The Reserve Bank should be able to cut interest rates until unemployment fell below 5% and approached 4.5% without worrying about inflation, Lowe argued.

And in May, in a report back from a board meeting, he made it clear that’s what he would do:

At that meeting, we discussed a scenario in which there was no further improvement in the labour market and the unemployment rate remained around the 5% mark. In this scenario, we judged that inflation was likely to remain low relative to the target and that a decrease in the cash rate would likely be appropriate.

It would likely be appropriate to cut interest rates and keep cutting until the unemployment rate was driven below 5%, continuing to cut until it approached 4.5%.

Today, appearing before the House of Representatives economics committee in Canberra with the unemployment rate still stuck at 5.2% despite two consecutive rate cuts, he delivered what on the face of it was bad news.

He said the bank’s central forecast was that the unemployment rate would stay above 5% again until 2021.

That’s right, 2021.

But taking the two statements together, it is reasonable to conclude that the Reserve Bank will keep cutting rates until unemployment does fall below 5%.

In other words, it will keep cutting rates until 2021.

Lowe ain’t done cutting…

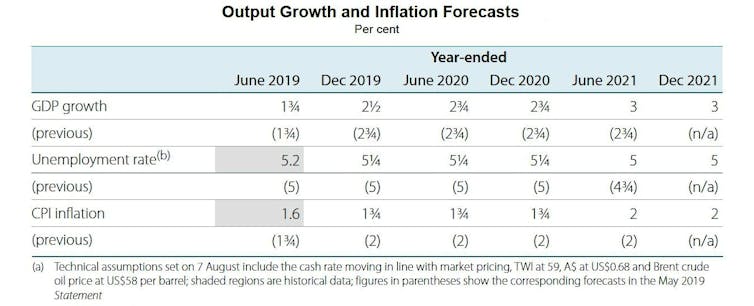

Indeed, the Reserve Bank’s quarterly forecasts update, released as Lowe spoke, countenances that happening.

As foreshadowed by the governor, it forecasts that the unemployment rate won’t fall back to 5% until June 2021.

And it contains several other unwelcome forecasts: economic growth of just 2.5% this year, down from a previously forecast 2.75%, and very weak inflation this year of just 1.75%, down from a previously forecast 2%.

But here’s the thing. All of those forecasts were compiled, as is the Reserve Bank’s custom, by taking into account not only the two interest rate cuts that have already happened (and have taken the bank’s cash rate down to an all-time low of 1%), but also two more yet to be delivered.

It is explained in the footnote:

Technical assumptions set on 7 August include the cash rate moving in line with market pricing.

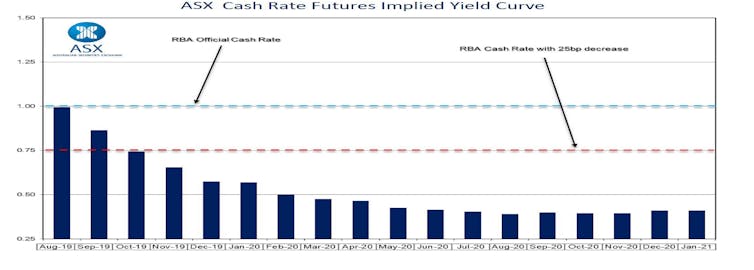

The “market pricing” is the consensus of the bets placed on the futures market for what the Reserve Bank is going to do to its cash rate.

The consensus is for another cut of 0.25% in October and then another cut of 0.25% in February, taking the cash rate down to yet another all-time low of just 0.5%.

The Reserve Bank is normally at pains to point out that this is a mere technical assumption, not a guarantee of how it will move rates.

But the awful truth is that its forecasts imply that unless it cut rates two more times in coming months, unemployment won’t fall to 5% by 2021, and inflation will be even weaker than the incredibly weak 1.75% it is forecasting.

…and he might not stop at zero

Two more cuts in its cash rate will take it to 0.5%, close to zero.

Lowe revealed that the Reserve Bank is investigating so-called “unconventional” monetary policy or quantitative easing that would have the same effect as taking the cash rate below zero.

“It is prudent for us to have done the work in advance to see what we would do – it’s really contingency planning,” he said.

Rates might go to zero, or below, worldwide because right now there is a worldwide glut of savings, and not enough investment.

The reality we face is that, if a lot of people want to save and not many people want to use those savings to build new capital, savers are going to get low returns. We can move our interest rates around this new structurally lower level,but we can’t escape the fact that global interest rates are low.

The Reserve Bank’s best case is that its Australian forecasts are wrong - that unemployment actually falls and that inflation, wage growth and economic growth climb.

There’s a respectable view within the bank that this might happen. Its forecasts take into account a range of positive influences, including lower interest rates, the recent tax cuts, the depreciation of the Australian dollar, a brighter outlook for investment in the resources sector, some stabilisation in the housing market, and ongoing high levels of investment in infrastructure.

But they are the result of a mechanical model that takes them into account individually.

The governor’s hope is that, taken together, they will achieve more than is forecast.

He would like governments themselves to push things along, starting with the wages they pay their own employees, and he is becoming ever more bold about saying so:

Most public sectors have wage caps of 2.5%, some have 1.5%, I think in Western Australia it’s probably even lower. I can understand why governments are doing that. On the other hand, the wage caps in the public sector are cementing low wage norms across the country. Over time, I hope the whole system, including the public sector, could see wages rising at three point something.

He is as good as powerless to stop what he regards as a worldwide investment strike caused by the trade and technology disputes between the United States and China.

These disputes pose a significant risk to the global economy. Not only are they disrupting trade flows, but they are also generating considerable uncertainty for many businesses around the world. Worryingly, this uncertainty is leading to investment plans being postponed or reconsidered.

Lowe doesn’t believe further interest rate cuts would to do much to encourage businesses to invest, or to encourage home buyers to borrow.

But he is certain they will help in other ways.

They will lower the exchange rate, making Australian goods and services more competitive, and that they will free up the cash of Australians who already have home loans, what he calls the “cash flow” channel:

There is no evidence that has become less effective. It is certainly true that in the current environment, at least in my view, monetary policy is less effective than it used to be. In today’s environment people don’t run off to the bank to borrow more when interest rates fall; they are more likely to pay back their mortgage more quickly. So that dynamic is different than it used to be.

When he last appeared before the parliamentary committee in February he said the probabilities of rates going up and rates going down were evenly balanced. He didn’t say that today.

Peter Martin., Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.