Australia’s housing debate has a habit of circling the wrong problems.

Every quarter, the ABS hands us another set of numbers showing where the market is actually heading - and every quarter, policymakers nod politely, shuffle some papers, and carry on as if the laws of arithmetic don’t apply to them.

The latest housing finance figures for the September quarter are another one of those “for heaven’s sake, can someone please join the dots?” moments.

And the charts and table below - especially the surge in investment loans and the tiny fraction going into building new homes - should be sparking warning lights.

Spoiler alert: they won’t. But they should.

Investors are back, and they’re back everywhere

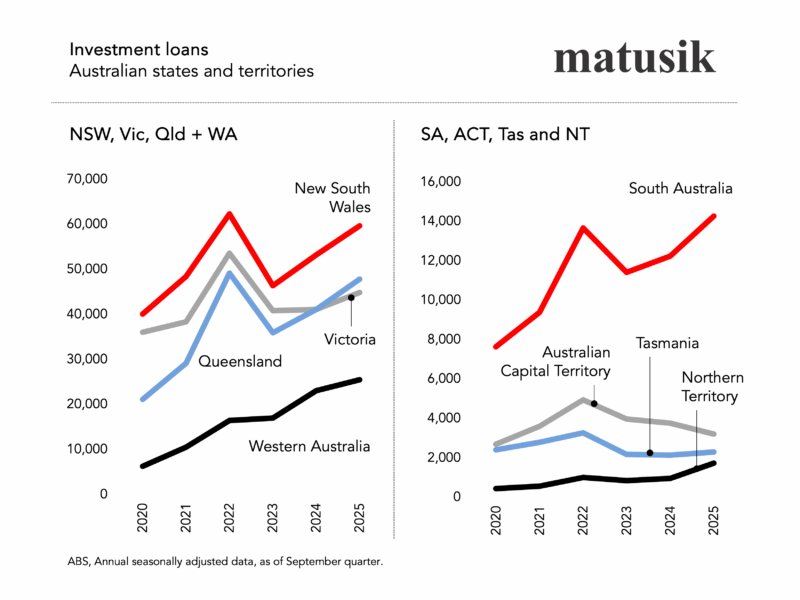

Investment loans are rising across the entire country.

New South Wales has jumped back toward 60,000–70,000 annual loans; Victoria’s trend is upward; Queensland remains solid; and Western Australia has almost tripled its investor activity since 2020.

Even the smaller states - South Australia in particular - are seeing strong investor acceleration. The ACT, Tasmania and the Northern Territory are modest but trending the same way.

See the charts below.

This is not a one-off. This is not a Sydney/Melbourne quirk.

This is a nationwide investor resurgence.

The catalyst? Lower interest rates.

Since the RBA’s first rate cut in February: Investor loan numbers and values are up 20%.

Meanwhile, owner-occupiers have barely moved: being up 2.9% in number and up 7.0% in value.

That’s a widening gap - and widening gaps always matter.

The investor share is now near peak boom levels

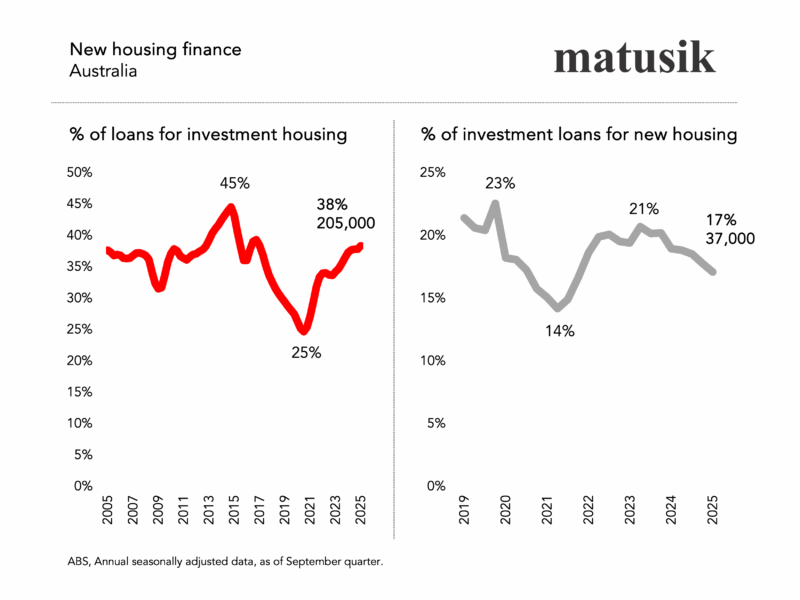

In the September quarter: Investors made up 38% of all housing finance, that’s 205,000 loans; and the highest share since 2017 and not far off the 2015 peak of 45%.

See the left panel of the chart below.

This is the same setup that forced APRA to intervene in the mid-2010s with caps on investor credit growth, limits on interest-only loans, and tougher serviceability tests.

The effect back then?

Investor demand cooled. Prices moderated. Owner-occupiers returned. The market stabilised.

We are now back in familiar territoy - but with higher prices, lower vacancy rates and a bigger structural shortage.

The actual problem: Investors aren’t building much at all

The right panel of the chart above shows the proportion of investor loans going into new housing.

And frankly, it’s embarrassing: only 17% of investor loans in 2025 went toward new homes.

This is down from 23% a few years ago and barely above the 2020 low of 14%.

Which means 83% of investor dollars go into established homes.

Not new supply. Not construction. Not anything that adds a roof to the national inventory. Not does it really add much to the Australia economy.

Four out of five investor loans simply reshape who gets to live in the existing housing stock.

That’s why investor activity doesn’t reduce rents. It doesn’t expand supply. It simply transfers ownership from one household type to another.

Some investors argue they’re providing “rental supply”.

True - but they’re also removing a home from the pool of dwellings available to buyers.

Net impact on total dwellings: almost zero.

The hard numbers

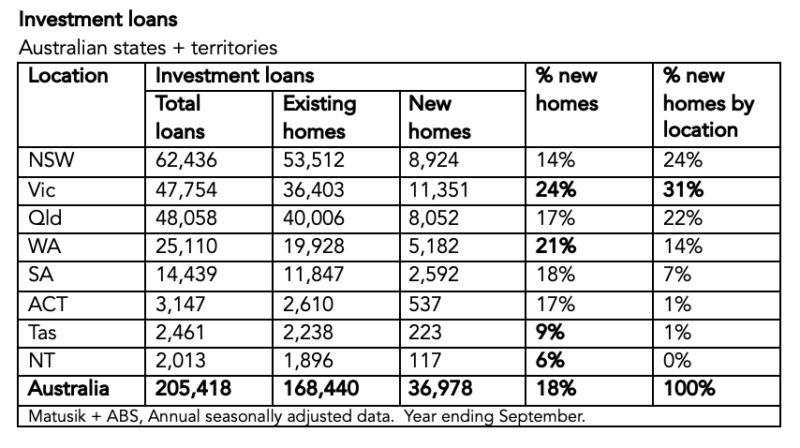

The investment-loans table makes it painfully obvious: 205,418 investor loans nationally; 168,440 for existing homes; only 36,978 for new homes and that’s a national average of 18%.

Interestingly, Victoria accounts for 31% of all new investor-built dwellings nationwide, while NSW - the biggest state - contributes just 24%.

It’s a lop-sided, supply-starving mess.

Tax policy drives the wrong behaviour

Investors overwhelmingly buy established dwellings because the tax system begs them to:

- negative gearing applies regardless of whether the home is new

- the CGT discount applies regardless of whether the home is new

- established homes offer higher land value and often higher capital growth

- lending is easier for existing dwellings

- building a new rental takes time, risk, delays and GST complications

We’ve created a system where property investment is highly rewarded - but actual housing creation is optional.

It’s like subsidising farmers to buy old crops instead of growing new ones.

Despite all the talk - housing accords, supply targets, 30-year plans, build-to-rent, you name it - the real-world outcome is the same: approvals down; housing starts down; completions down; construction finance weak; rents rising; vacancies scraping the floor; investor activity rising and new supply not responding.

We are stimulating demand while starving the supply pipeline.

Sadly we do it every cycle and yet do little to fix it.

Einstein apparently said that “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing yet expecting different results”.

Maybe insanity is the wrong noun, stupidity might be more apt.

So what would actually fix it?

Below a five reforms. All achievable. And frankly all obvious.

1. Limit negative gearing & CGT discounts to new homes only

The first and most important reform is to restrict negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount so that they apply only to new housing.

If an investor wants the tax concessions, they should be required to help add homes to the national stock.

If they prefer to buy established dwellings, the tax treatment should simply stop.

It is a clean, somewhat elegant and low-cost change that would immediately redirect investor demand toward the type of housing investment Australia actually needs.

2. Reintroduce APRA’s mid-2010s investor controls

A second reform is to reintroduce the lending controls that APRA deployed successfully in the mid-2010s.

Those measures - limiting interest-only lending, capping investor credit growth, tightening debt-to-income ratios and lifting buffers - cooled the investor boom of that era and created space for first-home buyers to re-enter the market.

Updating and reapplying these levers today would once again help steer finance away from pure speculation and toward activity that supports supply creation.

APRA is already concerned releasing a “System Risk Outlook” in November.

When comes to Australian housing remains a key financial-system risk, with household debt stuck near 1.8 times income for a decade.

Falling interest rates this year have reignited price growth, investor activity and some higher-risk lending.

While standards remain sound - for now - APRA warns rising indebtedness could heighten housing vulnerabilities and stands ready to apply macro-prudential controls if needed.

3. Create a “Build-to-Rent Lite” pathway for small investors

The third reform involves building a small-scale version of build-to-rent aimed at everyday investors - a “Build-to-Rent Lite” pathway.

This would give mum-and-dad investors meaningful incentives to build a new dwelling and rent it out, including accelerated depreciation, land-tax discounts, reduced stamp duty and fast-tracked approval pathways for small-format infill such as terraces, dual occupancies and secondary dwellings.

Instead of competing with first-home buyers for old stock, small investors would become small suppliers of new homes.

4. Reduce upfront taxes on new investor-built homes

Fourth, governments should reduce the heavy up-front tax burden that new investor-built homes currently carry.

Offering GST credits for new investment dwellings and lowering infrastructure charges for genuine supply additions would materially lower project friction.

New housing in Australia is disproportionately taxed compared to established dwellings; easing that imbalance would boost feasibility and lift output.

5. A time-limited ‘RentalBuilder’ incentive

Finally, a time-limited “RentalBuilder” incentive could act as a fast, targeted supply stimulus.

This would provide a modest credit to investors who commit to building a new home, finishing it within a set timeframe - say two years - and making it available for long-term rental.

Think of it as HomeBuilder re-engineered for actual supply creation rather than renovations.

A targeted, temporary and outcome-based nudge like this could materially lift new rental supply over a short period.

Final thought

We continue to reward speculation but not supply.

We subsidise demand but not construction.

We push investors toward established homes and then wonder why prices rise faster than building approvals.

The solutions aren’t complicated - just politically inconvenient.

If we want more rental homes, investors must be encouraged - and in some cases required - to help build them.