Key takeaways

Despite expectations that older Australians will downsize as they age, most are staying put.

Emotional attachment to the family home—filled with decades of memories—makes it hard to leave.

Downsizing has been "over-reported and under-appreciated"; the majority prefer to age in place, not relocate.

Boomers want to downsize locally, but suitable homes (smaller, accessible, well-designed) are lacking in middle-ring suburbs.

There’s a large, willing, and financially capable market of boomers ready to downsize—if we remove the roadblocks.

Do that, and it will not only benefit them, but free up homes for the next generation and create a more dynamic, fair housing system.

For years, we’ve heard the story: as Australians age they’ll downsize, trading big family homes for something smaller, more manageable, and more appropriate for their golden years.

That should, in theory, free up housing stock for younger families and smooth generational transitions in the property market.

But it’s not playing out that way.

Despite many boomers sitting on multimillion-dollar homes, many with no mortgage, few are taking the plunge.

Instead, they’re holding onto these large homes long after the kids have moved out, often rattling around in properties that are now far too big for their needs.

So, what’s going on?

For weekly insights and strategic advice, subscribe to the Demographics Decoded podcast, where we will continue to explore these trends and their implications in greater detail.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player:

The downsizing myth: overreported, underappreciated

There’s an assumption that older Australians will naturally trade down as they age.

But as Simon Kuestenmacher put it on our latest Demographics Decoded podcast, “The idea of downsizing is much over-reported and under-appreciated in Australia.”

Indeed, some Baby Boomers do make the move, often to lifestyle destinations like Noosa or the Gold Coast.

But these are the exceptions. Overwhelmingly, Australians prefer to age in place.

The family home is more than bricks and mortar to them.

It's a personal history, every room filled with memories of family, raising kids, birthdays, Christmases.

As Simon said, “A family home is more than just a box to live in... these are quite often wonderful memories and constant reminders of happier times.”

This emotional weight is a powerful anchor.

The missing middle: a housing gap that keeps Boomers stuck

If downsizing made emotional sense and suitable housing options existed, perhaps more boomers would consider it.

But here’s the reality: the required housing stock simply isn’t there.

Boomers want to stay in their neighbourhoods; they want familiar doctors, hairdressers, friends, and cafes.

But when they look around for a smaller, well-appointed, accessible home nearby, they often come up empty.

The middle-ring suburbs of our major cities are woefully underdeveloped when it comes to medium-density housing.

This is where boomers live, and where they’d like to stay, but development has been stifled for years by local councils and resistance to change.

Ironically, many boomers themselves were once NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard) who blocked the very developments they now need.

As Simon put it, “If there isn’t a suitable dwelling pretty much nearby, it won’t happen.”

It's not just sentimental—it’s also about stuff

Another underestimated barrier is clutter.

Downsizing means letting go, not just of space, but of decades’ worth of belongings.

Garages full of tools, sheds packed with “just in case” gear, wardrobes of rarely worn clothing.

It’s psychologically taxing.

Simon shared something that resonated with many: “If you downsize, you probably let go of 50% of your belongings. And your stuff holds you back. It ties you in.”

This is particularly difficult for men, who often associate their sense of identity with the physical things they’ve collected.

And yet, letting go can be liberating, both financially and emotionally.

But most people need to be ready for that transformation. Many aren’t.

The financial system is working against downsizing

It gets worse.

Financial disincentives actively discourage moving.

While there’s no capital gains tax on the family home, there’s stamp duty on the new purchase, a steep and immediate out-of-pocket expense.

For someone in their 70s, this is more than just annoying; it’s a deterrent.

And then there’s the pension asset test.

For retirees receiving a part pension, unlocking equity from a family home by selling it can affect their entitlements.

Suddenly, they’re “wealthier on paper” and lose access to financial support.

The result?

Many choose to remain in large, unsuitable homes to protect their pension income.

This creates what Simon called a “bizarre situation where we have countless widows on rather meagre pensions living in $2 million homes.”

It’s a system that penalises mobility and discourages right-sizing.

Policy changes that could unblock the pipeline

If we’re serious about solving the downsizing bottleneck, governments need to get strategic.

Simon laid out two simple, powerful ideas:

- A stamp duty exemption for downsizers – similar to the one we have for first home buyers - could create a one-time exemption for retirees selling their family home and buying their final residence.

- Reform the pension asset test – Ensure that retirees aren’t financially punished for unlocking equity. Perhaps allow a portion of home sale proceeds to be quarantined for future care or living costs without affecting the pension.

These changes could remove some of the biggest barriers.

As Simon said, “Kill the stamp duty, adjust the pension asset test - boom. That would make it financially juicy to downsize.”

Developers: start building what boomers actually want

There’s also a supply issue, and the private sector needs to play a role.

Most boomers don’t want to move into tiny apartments.

They want quality, accessible, spacious dwellings with good design, decent storage, walkable access to amenities, and a sense of community.

And they can afford it.

Australia ranks among the world’s wealthiest nations per capita.

According to the latest UBS World Wealth Report, Australia has the second-highest median wealth globally, most of it concentrated among baby boomers.

These are people who bought in the '70s and '80s and paid off their mortgages.

They’re sitting on enormous equity.

They just need the right housing to exist before they’ll move.

If developers focus on building right-sized, quality dwellings in middle-ring suburbs, there is a market, an affluent one.

If Boomers don’t move, who misses out?

The cost of this inaction falls squarely on younger generations.

As baby boomers stay in their oversized homes, their millennial children, many of whom are starting families, are pushed further to the urban fringe to find suitable housing.

That’s more time commuting, less access to schools, and less support from nearby family.

Ironically, this also limits the baby boomers’ own ability to stay involved with their grandkids’ lives.

And as we know, many older Australians want to be active grandparents, not just on the periphery but deeply involved.

That becomes harder when you’re 40 km away and the traffic is awful.

The clock is ticking—downsize before you Have to

The unfortunate reality is that many people leave the decision too late.

They wait until a health crisis forces their hand, a fall, a diagnosis, or the loss of a spouse.

Then the downsizing decision is no longer proactive, it’s reactive, stressful, and often rushed.

Simon offered a wise suggestion: “Make this decision as a couple, while you’re still healthy and active, in your early 70s or even 60s. That way, you remain in control, and you can design the lifestyle you want for the next chapter.”

And research backs this up: those who right-size early are more likely to live independently longer.

The mental and physical toll of staying too long in the wrong home isn’t often discussed, but it’s very real.

Downsizing isn’t just about space—it’s about freedom

At the end of the day, this isn’t just about square metres.

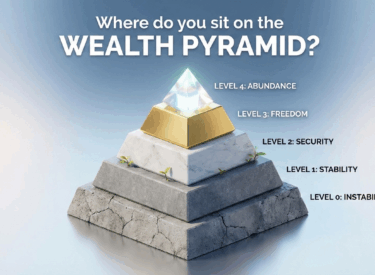

It’s about lifestyle, health, identity, financial security, and intergenerational equity.

It’s about creating smarter cities and more functional communities.

It’s about allowing people to live the lives they want, not just the ones they’ve inherited through inertia.

But if we want to unlock these benefits, we need to address both the psychological and structural roadblocks and give Australians the options, incentives, and support to right-size when the time is right.

The homes are there. The wealth is there. The need is clear.

Now it’s time for action.

If you found this discussion helpful, don't forget to subscribe to our podcast and share it with others who might benefit.

Subscribe now on your favourite Podcast player: