Affordability is one of those slippery words that gets thrown around, but there are a few accepted ways analysts and policymakers measure it.

They fall into three broad camps: price/rent to income ratios, repayment/rent burdens, and residual income tests.

And whilst there are warts on all methods I like to use price or rent to household income ratios as a test of an area’s level of housing affordability.

Price-to-income or rent to income ratio

- What it is: Median house price or median rent divided by median household income.

- Rule of thumb: A ratio above 5 or 6 is usually considered “severely unaffordable.”

- Limitation: Crude, as it ignores interest rates, deposit requirements, and living costs. But yet remains one if the better measures available.

And why I like it ?

It gives a clear sense of the barrier to entry - whether someone’s trying to buy or rent.

Sure, it’s most relevant to first home buyers, but it also applies across all renters.

And that’s what interests me: understanding and reducing those barriers.

My consultancy work always focuses on what needs to happen to help more people buy - or rent - a specific type of housing in a specific area.

Affordability is a critical piece of that puzzle.

Housing affordability — everyone talks about it, listen to me define it - and in just two minutes. Even I could tolerate it.

Modern metrics

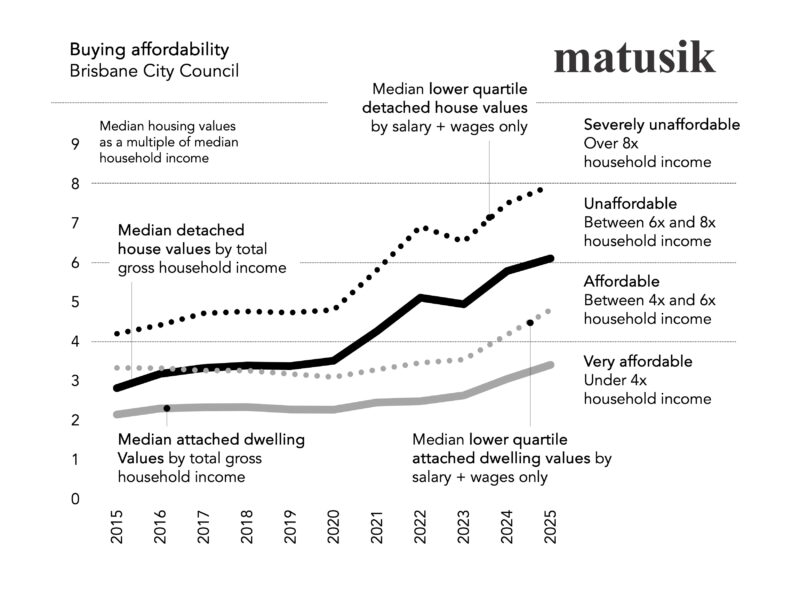

For years, the Demographia model has been the go-to measure of housing affordability — claiming homes are “affordable” if they cost three (3) times household income and “severely unaffordable” above five (5).

That might have worked when households had one income, strict lending, and few financial cushions. But today’s world is different.

My approach resets the ownership bands to reflect modern realities.

- Under 4× household income: very affordable

- 4× to 6×: affordable

- 6× to 8×: unaffordable

- Over 8×: severely unaffordable

Households now stretch further thanks to easier credit, dual incomes, government subsidies, shared living, and side hustles. It’s not painless, but it’s real.

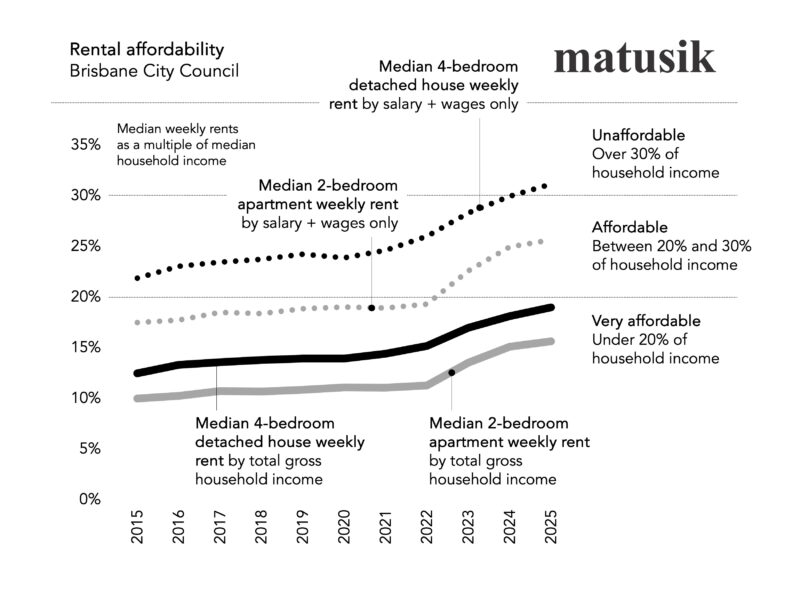

The same logic applies to renting. The old “30% rule” still defines rental stress, yet it’s crude.

My four-band system makes more sense:

- Under 20% of income: very affordable

- 20–30%: affordable but tightening

- 30-40%: unaffordable

- Over 40%: severely unaffordable

Together, these thresholds better reflect how households’ function today, factoring in multiple incomes, shared living, and government support and offer a more honest read on how Australians actually live, borrow, and rent.

They help identify where the barriers to entry really lie, and what needs to change to lower them.

But wait there is more.

I also track affordability using household incomes based solely on wages and salaries, rather than all components of a household’s income.

This often includes business income (outside of wages), investment returns, superannuation and government subsidies.

The wages and salaries focus offers a sharper lens for younger or lower-income households, who are often the most exposed to housing stress.

Against this measure, I compare the median values for the lower quartile detached and attached dwellings in the relevant area.

I also compare this income level with median rents, as many of these folks often rent.

Brisbane as a case study

This is an extract from the my current Brisbane Ready Reckoner Report.

Here we are talking about the Brisbane City Council area, which covers the area roughly within 20km of the Brisbane GPO.

Brisbane households today earn a median of $216,725 per year, with wages and salaries making up the majority at 60% or about $131,000 per annum.

The remainder comes from property income (17%), business returns (8%), superannuation (10%) and government transfers (5%).

While this looks like a solid income base, the reality is that growth in earnings has lagged well behind the surge in housing costs.

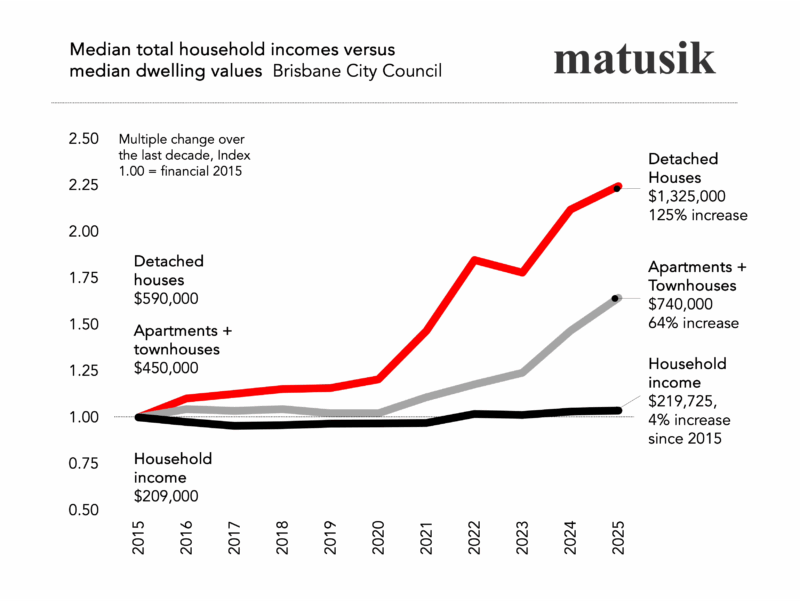

Since 2015, household incomes have lifted by just 4%. In contrast, detached house prices have risen by 125%, jumping from around $590,000 to $1.325 million.

Apartments and townhouses have fared slightly better in relative terms but still surged 64% to $740,000.

This divergence between income growth and dwelling values lies at the heart of Brisbane’s current affordability challenges.

Using my buying affordability benchmarks, Brisbane detached houses now sit above six times gross household income, placing them firmly in the unaffordable range.

Apartments and townhouses remain somewhat more accessible, but the trend line is pushing them closer towards the same category.

And for many younger households (or those reliant on what they earn in terms of wages or a salary) buying a house in Brisbane is now cactus.

Buying a unit is still possible for peeps starting out, but most of the older resale units that they can afford are either one-bedroom or tight two bedroom stock in old walkups.

Yes many of us started our property ladder that way, buy we were not paying 5x (or more) of our household wages from the get go, nor were the steps on the property ladder so wide.

Rental pressures are also mounting.

Four-bedroom detached houses now absorb close to 30% of household income, brushing against the affordability stress threshold.

Even two-bedroom apartments, once firmly within the “very affordable” bracket, now sit outside it.

For renters reliant on wages and salaries alone – particularly younger households and those without secondary income streams – the squeeze is even sharper, with many already in outright unaffordable territory.

These people - often Brisbane’s key workers - are now forced to live outside of the city boundaries in order to afford the rent.

Brisbane end notes

So based on 5x household income an affordable home for the average Brisbane resident - is $1 million.

Detached houses in the area currently average around $1.325 million.

Its gets much worse for the lower end of the market, where an affordable home needs to be in the $650,000 to $700,000 range (based on 5x wages/salary only which averages $131,000 per household), yet the median value in the lower quarter of house sales across the Brisbane City Council area is $1 million!

The result is a housing market increasingly out of step with local earnings.

Unless supply and pricing pressures are addressed, both aspiring homeowners in Brisbane face structural barriers that simple income growth will not overcome.

This has major consequences on social cohesion.

About 662,250 residents of BCC work.

And some 252,500 (38%) of these working residents are in ‘key worker’ industries such as health care, social assistance, policing and teaching.

Plus the cats that serve you coffee, wait your table and clean up after you.

Many key workers in BCC are also on moderate wages or salaries – falling within the bottom 50% of the household income strata – and they are currently being priced out of the private rental market; are unable to buy existing homes and especially new builds; and are leaving the region or a key worker position because of the lack of housing affordability.

When key workers leave due to housing stress, it’s not just a social issue - it undermines health, education, and other local infrastructure - slowing economic growth and future investment in the region.

Also, key workers need to live close to hospitals, schools, government offices and depots where they work.

Long commutes or relocations to cheaper fringe suburbs aren’t feasible for shift workers or on-call staff.

I recently quipped - out of increasing frustration at a development industry function about this stuff - that “it’s hard to run a hospital from the hinterland!”

Also how far can housing values really grow if household incomes don’t accompany housing values?

They might not be in lockstep these days but they need to have a closer relationship than they do now, let alone in the future.

And importantly something needs to be done about Brisbane’s new affordable housing supply.

Unlocking this supply requires modest but targeted reforms.

Changes to setbacks, site cover, building heights, parking requirements, and construction methods could lift project viability and increase yields.

Incentives, faster approvals, and new housing types - from small-lot homes and terraces to secondary dwellings and plexes - can further boost affordable housing delivery.

Without action, Brisbane risks worsening affordability, workforce displacement, and declining liveability.

Unfortunately, Brisbane’s experience isn’t an outlier — it mirrors what’s happening across most of Australia’s housing markets.