Every time interest rates move up or down, we are asked the same question: “Should I fix my mortgage rate?”

It’s a fair question – especially after the rollercoaster of recent years.

Many borrowers are still feeling the sting of higher repayments and are tempted to lock in some certainty.

But as with most financial decisions, the best answer is not based on gut feeling – it’s based on evidence.

Therefore, I wanted to unpack what a “normal” interest rate really looks like, how to think about the RBA’s neutral rate, and what decades of data reveal about when (and when not) to fix your mortgage rate.

What is a normal interest rate?

We could look back at historical mortgage rates to estimate what might be considered an “average” interest rate, but that data may not be particularly reliable.

That’s because the lending environment has changed dramatically over the past few decades.

For instance, the interest rate discounts lenders offer today are far greater than what was available before the GFC.

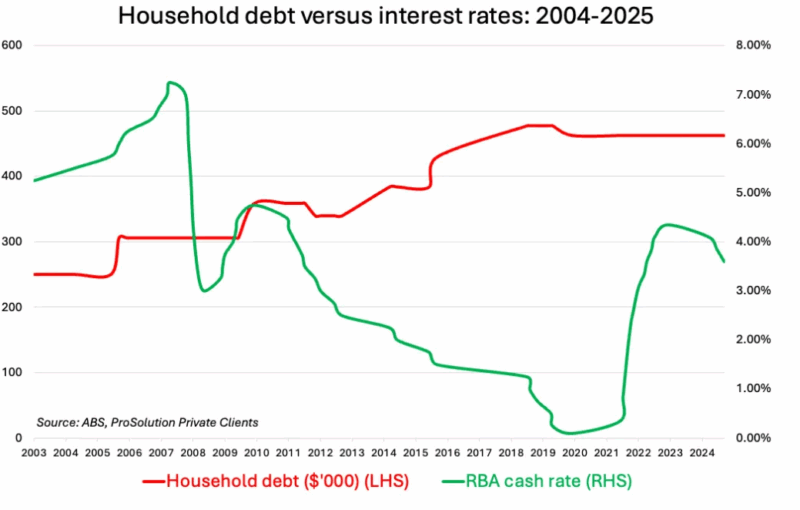

A better reference point is the RBA Cash Rate, shown in the chart below, compared to household debt (adjusted for inflation).

The key takeaway is striking; household debt has almost doubled since the early 2000s. That means households are now far more sensitive to interest rate changes.

In practical terms, this suggests the RBA does not need to push rates as high as it once did to achieve the same cooling effect on the economy.

For example, the cash rate reached 7.25% before the GFC and 7.5% in the mid-1990s.

By contrast, the recent peak cash rate of 4.35% was enough to slow consumer spending significantly, though it would help if the government curbed its spending too!

Over the past 10 years, the time-weighted average cash rate was 2.11%, and 3.37% over the past 20 years.

Of course, the Covid years of very low rates distort this picture.

Excluding that period, the averages rise to 2.59% for the decade before Covid and 3.97% over the two decades prior.

All of this reinforces a clear conclusion: because households are carrying much more debt today, interest rates do not need to return to the levels of the 1990s or 2000s to have the same economic impact.

This insight helps inform long-term decision making.

What is the neutral rate?

When planning your personal financial strategy, it’s sensible to base your assumptions on a neutral cash rate and then stress test your ability to service debt by adding 1% to 2% on top.

This helps you understand whether your finances could comfortably withstand higher interest rates.

The neutral cash rate is a useful guide because it represents a level that neither stimulates nor restricts the economy – effectively, it’s the long-term “steady state.”

The RBA recently estimated the neutral rate to be around 2.75%, while most economists believe it’s closer to 3.5%.

In truth, it’s impossible to measure precisely in real time, and it naturally shifts over time as structural factors in the economy change.

Based on the neutral rate estimates and historical averages discussed above, we believe it’s reasonable to assume a long-term cash rate in the range of 3% to 3.5% per annum.

At present, variable principal-and-interest (P&I) home loans are typically priced 2% to 2.5% above the cash rate, while interest-only (IO) loans are 2.5% to 3% above.

That means a sensible long-term average assumption would be:

- 5% to 6% p.a. for home loans (P&I)

- 5.5% to 6.5% p.a. for investment loans (IO)

In other words, these ranges should be viewed as normal.

Current interest rate settings aren’t unusually high, they’re within a healthy, sustainable range.

If you are finding it difficult to service debt at today’s levels, that’s a warning sign you may have borrowed too much, or you are spending too much on living expenses.

Most fixed rate borrowers are losers

You probably know I’m a strong believer in making evidence-based financial decisions.

Doing so helps you avoid costly mistakes.

After all, if the data clearly shows that fixing your mortgage rate is usually a losing bet, you would be silly to ignore that data.

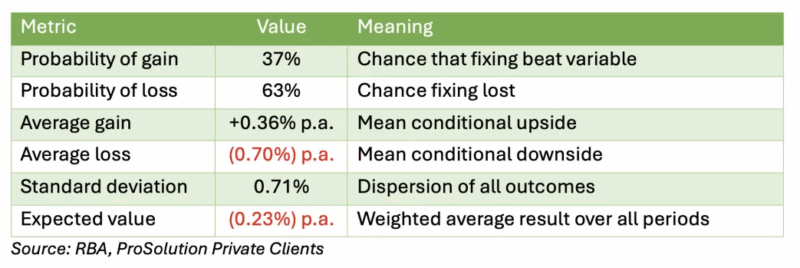

The RBA has tracked 3-year fixed mortgage rates since 1990, so I analysed whether borrowers who fixed were better or worse off over that time. The results were telling.

From 1990 to 2025, 65% of fixed-rate borrowers were worse off.

If we exclude the unusual Covid period, when the RBA was effectively lent to banks at just 0.10% p.a. fixed for three years (that probably won’t happen again in our lifetime), the figure rises to 71% worse off between 1990 and 2020.

However, comparing interest rate settings from 35 years ago is not particularly meaningful today.

So, I focused on the 20 years prior to Covid (2000–2020) – a period more reflective of the current interest rate environment.

Here’s what I found:

- Fixing your rate left borrowers worse off 63% of the time, and better off only 37% of the time.

- When fixing helped, the average saving was +0.36% p.a.

- When it hurt, the average cost was –0.70% p.a.

In short, the odds were roughly two-to-one against fixing, and the downside was about twice as large as the upside.

On a risk-adjusted basis, that translates to an expected cost of around 0.23% p.a. for fixing your rate.

Put a high value on flexibility

Based on the above, from a purely financial perspective, history tells us that fixing your interest rate probably isn’t going to work in your favour.

However, there are other important factors to consider.

Fixed-rate loans come with several key limitations compared to variable-rate loans:

- Break costs: If you need to repay or refinance during a fixed period, you could face significant break fees. These depend on how market rates have moved since you locked in. If fixed rates fall after you fix, the penalty can be substantial, sometimes tens of thousands of dollars. If rates rise, there may be little or no cost.

- No offset account: Most lenders don’t allow an offset account to be linked to a fixed-rate loan (though there are some notable exceptions, such as Adelaide Bank, Bank Australia, and Bendigo Bank). Offsets are valuable because they allow you to park cash savings and reduce interest without losing liquidity, an especially useful option for investors because it preserves the tax-deductible nature of the debt. One way to retain this benefit is to fix only part of your loan and link an offset to the variable portion.

- Limited extra repayments: Fixed-rate loans usually cap extra repayments at between $10,000 and $30,000 over the fixed rate term. Again, splitting your loan between fixed and variable can help preserve flexibility.

- Reduced refinancing and equity access: Being tied to a fixed rate, and the potential break costs that come with it, can limit your ability to refinance. This might prevent you from optimising your borrowing structure, accessing higher valuations, or taking advantage of a lender with better credit policies for your situation.

Personally, I place a high value on maintaining flexibility.

The ability to restructure loans, release equity, or adjust your strategy as circumstances change is often worth far more than any potential small savings you could enjoy from fixing.

So, before locking in, carefully consider what flexibility you might be giving up, and if you do decide to fix, structure your lending to keep as many options open as possible.

Best time to fix is…

When analysing the best times to fix over the past 35 years, two distinct periods stand out when fixed-rate borrowers came out ahead.

The first is obvious – the Covid period from late 2020 to early 2022.

During this time, the RBA slashed rates and lent to banks at virtually zero (0.10% p.a. fixed for three years).

Unsurprisingly, borrowers who locked in during this window did exceptionally well, often saving between 2% and 3.5% p.a. compared to variable rates.

The other period was between early 2005 and mid-2006.

Borrowers who fixed 3-year rates at just under 7% p.a. were insulated from the RBA’s subsequent hiking cycle, which pushed mortgage rates from the high-6%s to almost 9% in the years leading up to the GFC.

In both cases, it’s probably fair to say borrowers couldn’t have reasonably predicted what came next – just as those fixing in 2021 couldn’t have known rates would surge one to two years later.

However, when fixed rates are so obviously below what’s sustainable (as they were in 2021, below 2%), fixing becomes an easy decision.

So, my conclusion is this:

I would only consider fixing my mortgage rate in one of two situations:

- When the deal is so clearly in my favour (like 2021), and/or

- When I need protection because rising rates would place unacceptable pressure on my cash flow.

In every other scenario, flexibility, and optionality matter far more.

Should you fix now?

In short, no.

History shows that fixing your interest rate is more likely to leave you worse off.

At the time of writing, fixed rates are only marginally lower than variable rates.

Three-year home loan (P&I) fixed rates sit around 5% to 5.5% p.a., while investment (IO) fixed rates range between 5.3% and 5.8% p.a.

Interest rates for some shorter-term periods, such as 1 to 2 years can be even lower.

While most economists expect interest rates to remain steady for a while, it’s important to remember that rate expectations can literally change overnight.

Markets and central banks react to new data and unexpected global events – things that are unpredictable today.

That’s why trying to “outguess” interest rate movements rarely works.

Current interest rates are set by global money markets and already full reflect current expectations.

The evidence overwhelmingly supports staying variable rather than locking yourself into a rate based on what you think might happen next.

It’s worth mentioning that a few less-scrupulous mortgage brokers might suggest you fix your rate, not because it’s in your best interest, but because it secures their commission income.